| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XIX Number 16. . . .December 21, 2012

excerpt:

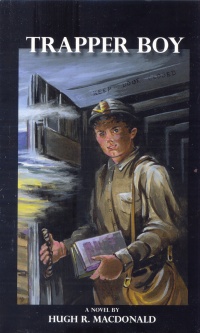

Trapper Boy covers four months in the life of 14-year-old John Wallace Donaldson, known as "J.W." The year is 1926, and J.W, who lives in Sydney Mines, N.S., is graduating from Grade Eight. He wins two silver dollars for coming first in two subjects, but his friend, Beth, who ties with him for the best marks in English, gets the award he covets, a collection of classic novels. This beginning, which shows Beth and J.W. preoccupied with typical teenage concerns, foreshadows their future, for it is Beth who continues in the world of books and J.W. who must enter the world of wage earning. Author Hugh R. MacDonald drops a further hint of what lies in store for J.W. when he and Beth note that they don't see much of their pal, Mickey, any more. Ever since he went into the mine as a trapper boy, he's always sleeping. MacDonald tells his story in the third person, mostly from J.W.'s point of view but occasionally from that of his parents. Through them, readers soon learn that, to survive, the household needs two wage earners. The family is resourceful, growing a garden, picking wild berries, fishing, and snaring rabbits. MacDonald uses vivid, carefully selected, symbolic detail in presenting the underground world. On J.W.'s first shift, a rat runs up his leg. He throws it against the wall, injuring its leg. Almost immediately, he feels sorry, and, in the days to come, he makes sure it gets its share of oats from the pit horses' feed. Although some of the miners kill rats, J.W. believes that they serve a purpose, like canaries in a mine. When they rush out of an area, they warn the miners of danger. J.W. names his pet rat "Tennyson" and eventually sets it free. In Emile Zola's Germinal, the blind pit ponies whose entire lives are spent underground symbolize the miners, but in this novel, the symbolism is more cheerful. Tennyson's liberation foreshadows J.W.'s release from work to which he is not suited. The rat sections reminded me of a scene in D.H. Lawrence's Sons and Lovers where the coal miner father tells his young children about his pet mice underground. Throughout the novel, the author presents the miners as strong, cooperative, capable and daring. He also shows that they are more than just their jobs. Red, the shift boss, is a wise and helpful mentor for new workers; Smitty, from Barbados, quotes poetry from memory, and Andrew Donaldson demonstrates skill and precision in his drawings of life underground which explain the mine to his son. The black and white illustrations, supposedly drawn by the fictional Andrew Donaldson, are by the real life artist Michael G. MacDonald. They appear singly throughout the novel, then all together in a mosaic, and are crucial to the plot. From looking at them, and from exploring the mine with his friend, Mickey, J.W. knows of an abandoned tunnel only about three or four feet from Tunnel Seven. Eventually, he uses this knowledge in a timely and brave way. Subsequently, he uses his father's drawings in another bold move that improves his family's finances. Among the great novels about coal miners is Richard Llewellyn's How Green Was My Valley in which a strike is central to the plot. Perhaps Hugh. R. MacDonald will write another novel which focuses on union activities and labour actions in Cape Breton mines. J.B. McLachlan, a real life famous trade union leader, is mentioned but does not appear in the action of Trapper Boy; however, an Internet search suggests that the struggles he led could provide material for several novels. While reading Trapper Boy, I remembered my father's first cousin, the late William George Bott of Linton, Staffordshire, England, who went into the mines at age 14, like the fictional J.W., and who had interesting tales to tell when I met him in his old age. Hugh R. MacDonald manages to educate without being didactic, and his upbeat ending has a bittersweet element which makes it realistic. Trapper Boy is excellent literature and ought to win prizes. Congratulations to the author and to Cape Breton University Press for bringing this novel into being. Highly Recommended. Ruth Latta's work in progress,"The Song Catcher and Me", is an historical novel with a 14-year-old central character. Ruth lives in Ottawa, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- December 21, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |