| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XIX Number 16. . . .December 21, 2012

excerpt:

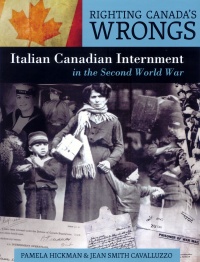

The sad story of the internment of Japanese-Canadians during World War II, a shameful example of systemic discrimination enacted as policy by Canada's war-time government, is now well-known. Italian Canadian Internment in the Second World War, co-authored by Pamela Hickman and Jean Smith Cavalluzzo, shows that Japanese-Canadians were not alone in experiencing collateral damage. The second volume in the "Righting Canada's Wrongs" series, this book follows much the same format as the preceding volume, Japanese-Canadian Internment in the Second World War, (Vol. XVIII, No. 35, May 11, 2012) beginning with an overview of the social and economic conditions leading to Italian immigration to Canada. As was the case throughout much of 19th century Europe, a steady stream of Italians left their homeland following 1870. Much of that country's populace was agrarian, desperately poor, and incapable of paying the taxes imposed by the new unified Italian government. By the 1930's, the Italian immigrant community in Canada numbered more than 100,000. Most worked in construction or related skilled building trades, but some became small businessmen, and others found work on western Canadian farms and in the orchards of British Columbia. Miners from southern Italy found work in Northern Ontario and Cape Breton, and Hamilton's steel industry became a major employer. But, life in Canada was not easy, and many were disappointed at having exchanged one arduous existence for another. A familiar quotation was, "The streets were not paved with gold. The streets were not paved. We were expected to pave the streets."(26) However, like many immigrant groups, the Italians had a strong work ethic and a very strong sense of community."Little Italies" developed in cities such as Toronto, Montreal, Hamilton, Windsor and Winnipeg, and the churches, restaurants, food shops, and social clubs maintained culture, language, and ethnic identity. And, like immigrants from other European nations, Italians "came to a country where racist attitudes and conduct towards many groups was common and socially accepted."(44). Even as they adapted to Canadian life, Italian immigrants retained strong ties to family who remained in Italy and a strong sense of connection to their heritage country. With the rise of Fascism, those connections, however innocent, became suspect. During the 1920's and 1930's, under Mussolini, Italy's stagnant economy turned around, and the creation of some key social services led to a much better standard of living. The Fascists also worked to promote their cause amongst Italian ex-pats, and so, by the late 1930's, there was a cadre of pro-Fascist support among some Italian-Canadian organizations. By 1939, when Canada declared war on Germany, the RCMP had been watching the Italian immigrant community and compiling lists of Fascist sympathizers. Mussolini's alliance with Hitler was a shock to many Italian-Canadians, and once Canada declared war on Italy, life became difficult for them. As was the case within the Japanese-Canadian community, young men enlisted in the Canadian military, people bought Victory Bonds, held fund-raisers for the Allied cause, planted Victory gardens, and school kids collected salvage – metal, paper, and other items which could be recycled for use in the war-time economy. These efforts were important demonstrations of patriotism: "We were Canadian born and just trying to show that we too were Canadians."(55) In 1940, the War Measures Act was applied: Italian-Canadians over the age of eighteen were declared "enemy aliens" (as well as those who became citizens after September 1, 1922), organizations considered to have Fascist leanings were declared illegal and shut down, and those individuals named on RCMP listings of alleged Fascist or Communist supporters were arrested. Shops and businesses owned by Italian-Canadians were vandalized, children were taunted and bullied in the schoolyard, and many suffered ostracism and workplace discrimination. "My two sisters arrived home from work crying and upset because they had been fired from their jobs. . . . They were both told that unless they could prove they or their father was a Canadian citizen they would be fired. The whole family was upset about the potential loss of family income and the fact that my sisters were being fired basically because of their ethnicity."(65) Nearly 600 men were interned, either at Camp Petawawa, ON or Camp Ripples, NB. As well, four women were held at Kingston Penitentiary for Women. The book contains facsimiles of letters (always censored) sent by family members to the men in the camps, and those letters are poignant. "Many internees told stories of men crying while reading letters from home"(70), as they knew that their families were experiencing terrible privation since their internment meant loss of the family's income. For all Canadians, life on the home front was challenging; for those in the Italian Canadian community, it was compounded by stigma, a loss of community leadership and an unwarranted sense of shame. Only after internees were detained did the Canadian Government actually begin investigating the degree to which these men actually constituted any sort of security threat. Some were released within months, while others remained in detention for years. Even after their release, internees often experienced discrimination in the work force or in their former neighbourhoods. Some were able to resume life as it was but experienced long-term guilt, embarrassment, or a sense of betrayal by others from their ethnic community. Some chose to anglicize their names or deny their cultural roots. However, changes in post-war immigration policy led to an influx of immigrants from post-war Italy and, with settlement in cities having established Italian Canadian communities, the Little Italies of Toronto, Windsor and Winnipeg revived. Several years after Canada's official apology to the Japanese-Canadian community, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney made a statement of apology, but, as the statement came in a context from outside Parliament, it lacked "official" status. Internees have never been granted financial compensation, although there has been some government backing for programs supporting museums, memorials, books, and similar activities to enhance awareness of the Italian-Canadian internment experience. But, is it enough? Even today, the Italian-Canadian community is divided on the subject of whether to fight for further redress, or to move on. Even if a community can "move on", a story like this should never be forgotten. Italian Canadian Internment during the Second World War does an excellent job of telling the story of an ethnic community subjected to grossly unfair treatment and systemic discrimination, both by fellow Canadians and, most regrettably, the Canadian government. The book features a wealth of well-captioned visual material: colour and black and white photos, facsimiles of personal and government documents, and most powerfully, first-person accounts from the many who suffered as a result of the War Measures Act. Throughout the book, icons titled "Watch the Video" direct readers to excellent visual and audio content posted on the web-site, Italian Canadians as Enemy Aliens. (http://www.italiancanadianww2.ca) A Timeline providing significant events in the development of Canada's Italian community, a Glossary, and a listing of materials For Further Reading, all add to the book's value as an acquisition for high school libraries and as a supplementary work for use in social studies classrooms. Italian Canadian Internment in the Second World War is most useful, both as a source of information on the history of Italian immigration to Canada and of the human rights violations that were enacted by the government of Canada while fighting a "just war". Highly Recommended. Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- December 21, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |