| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XI Number 14 . . . . March 18, 2005

excerpt:

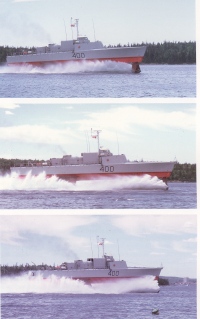

There are two stories in Fastest in the World, both ones of experimentation, frustration, disappointment and failure. The first deals with attempts by Alexander Graham Bell and Frederick Walker Baldwin to develop a hydrofoil at Bell's summer home in Cape Breton Island. The second tells the history of the Bras d'Or, a hydrofoil developed for the Canadian navy. A hydrofoil is a boat, which runs on foils, or vanes that raise the vessel out of the water. Because it is elevated and there is much less drag from the water, a hydrofoil travels a great deal faster than ordinary ships. It was an idea which held much promise but met with little success. Bell's is the best-known name in the book. The experiments on the hydrofoils, however, were carried out by Baldwin who extensively tested every version. Bell considered himself to be a "problem solver" rather than an inventor, even though Canadians consider him to be one because of his work on the telephone. His role in this case was one of advisor and mentor while his wife, Mabel, provided the funding for the experiments. Bell's association with Baldwin began in 1906 when he was 59 and Baldwin 24 and lasted until his death in 1922. Baldwin continued with his experiments long after Bell's death. The Bell/Baldwin saga is one of great disappointment. Most of Baldwin's attempts to create a hydrofoil ended in failure. Their story reminds one of the ancient alchemists who tried to change lead into gold. Many of the ships fell apart, and Baldwin, who drove them, ended up in the water on several occasions. While there was considerable interest in his later efforts from various navies, none resulted in contracts and no money was made. Like the alchemists, failure was his only reward. Success of a sort was achieved with the construction of the Bras d'Or in the 1960s. Built for the Canadian navy who wanted to use it to search for and destroy submarines, it, too, turned out to be a flop. While there was considerable excitement when it made its maiden voyage from Halifax to Bermuda and Virginia (in an attempt to interest the Americans), before returning to Halifax, nothing materialized as a result. Even the Canadian navy lost interest.

Fastest in the World has an index, bibliography, glossary and a chronology of hydrofoil development. It is illustrated throughout with functional black and white and coloured photographs. While it deals with a part of Canadian naval history, it would not be suitable as a text. Neither would it be much fun as recreational reading. To attract the attention of readers, particularly young ones, history needs to be more challenging and thought-provoking. It needs to come alive which Fastest never does. The book is factual, but there are so many small details the reader loses interest. There are a number of poorly written sentences in Fastest. "There was speculation that the Minister paving way for a cancellation announcement." is one example. While these are minor, they reduce the book's appeal and should have been caught during editing. The information in the chapter on the Bras d'Or's maiden and final voyage is not written chronologically. The 1971 voyage to Bermuda is discussed. This is then followed by information on the preparation of the ship for this journey in 1970. Once the problems encountered in its preparation are discussed, the text returns again to the ship's only voyage. This is confusing. Recommended with reservations. Thomas F. Chambers is a retired college teacher living in North Bay, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- March 18, 2005.

AUTHORS

| TITLES | MEDIA REVIEWS

| PROFILES

| BACK ISSUES

| SEARCH | CMARCHIVE

| HOME |

John Boileau served in the Canadian army for 37 years. He has written many historical articles for

magazines and newspapers and was Consulting Editor for a book on the Canadian military, A

Century of Service: Canada's Armed Forces From the Boer War to East Timor. In spite of his

enthusiasm for his subject, Fastest In The World is not that interesting. Reading about failure is

not exciting. While Baldwin did construct the fastest boat in the world, no use was made of his

ideas until the construction of the Bras d'Or many years later. Even this unique ship only made

the one voyage before it was retired from service. The ship never sailed again after its trip to

Bermuda.

John Boileau served in the Canadian army for 37 years. He has written many historical articles for

magazines and newspapers and was Consulting Editor for a book on the Canadian military, A

Century of Service: Canada's Armed Forces From the Boer War to East Timor. In spite of his

enthusiasm for his subject, Fastest In The World is not that interesting. Reading about failure is

not exciting. While Baldwin did construct the fastest boat in the world, no use was made of his

ideas until the construction of the Bras d'Or many years later. Even this unique ship only made

the one voyage before it was retired from service. The ship never sailed again after its trip to

Bermuda.