| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XI Number 14 . . . . March 18, 2005

excerpt:

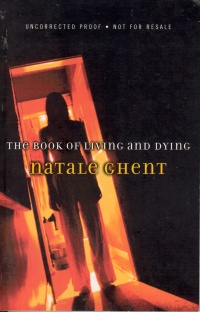

In Natale Ghent's The Book of Living and Dying, the daily experiences of a high school senior, Sarah, are punctuated by horrible flashbacks to hospital scenes. Sarah is mourning the death, from cancer, of her elder brother John. These unpleasant memories relate to his terminal illness. Or do they? Sarah is haunted by her brother. The odor of earth and rain signal his approach. His appearances, to sit on her bed, are not a source of comfort; rather, she pleads with him to go away. Ongoing headaches plague her, for which she takes codeine. Sarah has no adult to confide in, as her father predeceased her brother, and her mother is withdrawn. At school, she has only two friends, Peter, who is over-protective and wants to be her boyfriend, and Donna, a daring rebel. This highly descriptive and evocative work seems to be moving along the lines of a traditional teen "problem novel," until Sarah meets a new student. His name, Michael Mort, should signal to anyone who knows French that he is more than just a teenage boy. Michael Mort looks older than seventeen and sports a goatee. His "dark, brooding looks" convey "thinly veiled disdain." He has a coyote tattooed on his shoulder and explains that in mythology it is a trickster with the power to assume other forms. Michael Mort's hobby is taking still photos and animating them, creating videos in which the person seems to be alive. He makes such a video of John. He and Sarah fall in love. Donna suggests that John may be haunting Sarah because he is "in limbo" and having trouble "crossing over." In a book store, the girls come upon a Book of Living and Dying, which may be the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Sarah reads that hauntings are rarely violent but are generated by the living person's thoughts of the deceased and their incapacity to atone. Death can be confusing for the dead, she reads. They can get lost on their journey. The living must hold a ritual so that the dead person knows what has happened to him. Author Natale Ghent excels in employing tried-and-true symbols and plot devices to create an unsettling atmosphere. These include trap doors, woodland circle ceremonies with magic mushrooms, Tarot cards, a visit to Salem and a fortune teller. The dying kingfisher, which appears toward the end of the novel, ultimately ties in with a broken blue bottle but is interesting as an allusion to the Fisher King, a legend of death and rebirth that one finds in the Arthurian legends, in Percival, and The Wasteland. The cover blurb of this novel suggests that it is a cautionary tale about the consequences of abusing alcohol and drugs and taking up with bad companions. It isn't! Rather, it is a story of the supernatural in the same category as the movies, Sixth Sense and Crossing Jordan. For much of the story, Sarah does not know what is real and what she is imagining, and neither does the reader. One assumes that the hospital flashbacks pertain to John's illness, but since the patient is not specified, they could apply to Sarah, as could Donna's remarks that the dead sometimes don't know they're deceased and must be eased into death. This novel cries out to become a horror movie. Along with staple devices from film and literature, Ms. Ghent brings her own warped slant on something as wholesome as the coming of spring. Sarah, looking out her window, sees the hatching of baby birds as depressing. More birds fighting for the right to breed. More nests built. More eggs laid. More chicks to hatch and scream for food, only to be blown out of the trees at the faintest hint of wind... Come April, the sidewalks would be littered with fledglings hop-hop-hopping innocently along...[P]itiful squawks as they eventually succumbed to neighbourhood cats... It was fitting, thought, that so much death be associated with so much life. Some must go so that others may come.... These sentiments are not contradicted or counterbalanced by another character's thoughts or by authorial input. To this reader of mature years, such resignation, after so many creepy scenes and troubling allusions, is shocking. Although readers of seventeen or eighteen have seen much film involving the supernatural, I feel that they are too young for something so relentlessly downbeat. The hospital scenes alone are enough to paralyze a reader. Too many of our fledglings are dying; one has only to turn on the TV to the latest war news or reports on street youth and teen suicide. I found nothing hopeful or uplifting in the novel. I hope readers in their late teens are jaded enough to realize that author Ghent is elegantly and artistically pushing our horror buttons. This old reviewer found it a relief to close the book and come out into the daylight. Not Recommended. Tea With Delilah, a cosy mystery, is Ruth Latta's latest book. Ruth lives in Ottawa, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- March 18, 2005.

AUTHORS

| TITLES | MEDIA REVIEWS

| PROFILES

| BACK ISSUES

| SEARCH | CMARCHIVE

| HOME |