Shizue’s Path

Shizue’s Path

The country of my parents attacked Pearl Harbor. A war from far across the ocean washed up on our new country’s shore.

I wish I could skip this chapter of the story, darling, just as you may want to skip parts of your own life story in time. But you see, you mustn’t do that.

You need to know your darkness to know your light.

And I can see so much light in you.

So I’ll keep going through the dark.

But I’d love for you to hold my hand.

With the recent proliferation of books about Japanese Canadians’ internment during the Second World War, Mark Sakamoto’s Shizue’s Path, illustrated by Rachel Wada, is another offering for young readers that focuses on this era. Written by authors of Japanese heritage, many of these books accentuate the humanity of the Japanese Canadian communities they represent and illuminate for contemporary audiences the injustices that they have endured. In doing so, they validate and affirm the value of their experiences within Canada’s continually evolving historical narrative.

Sakamoto’s Shizue’s Path takes a somewhat different approach to Japanese Canadians’ experiences, one that distinguishes it from other picture books. Taking inspiration from his great-aunt’s life, Sakamoto situates his story against the backdrop of the Second World War, with the story revolving around a young girl whose family and other Japanese Canadians are experiencing increasing discrimination and injustice as a result of their cultural heritage. However, Sakamoto does not simply explore the war’s impact on Japanese Canadians and then rehabilitate them as individuals whose experiences must be remembered. Instead of representing Shizue’s experiences within a closed temporal frame, he embeds them within a broader narrative that connects her past to the present and future. Sakamoto uses that historical era as a catalyst for reflecting on what the past means in the contemporary context and what responsibility people should have towards that past.

Structurally, the narrative unfolds as a dramatic monologue from the perspective of an elderly Japanese woman named Shizue to an unspecified listener who is a young girl. In the book’s opening scene, the elderly woman thanks her young visitor for coming and invites her inside, where she shares her memories. Initially, Shizue lives a normal life like other children, but her life is irreparably changed with the advent of the Second World War. Divested of their property and belongings, she and her family are forcibly removed from their home and herded off to internment camps where they have to toil in the fields and live in inadequate shelters. Even after war, they continue to experience discrimination as they attempt to rebuild their livelihoods. Shizue is one of the fortunate ones as her father is able to get her into a university. When she observes a rally that is protesting the government’s plan to send every person of Japanese ancestry back to Japan, she is inspired to devote her life towards healing and helping others, a decision which leads her to pursue a career in therapy. The book’s narrator mentions that her granddaughter has adopted the same attitude by participating in rallies for other causes such as climate change and Black Lives Matter. The narrative is brought full circle when the woman thanks her visitor for listening.

The relationship between the woman and girl is not specified, but readers may surmise that the two of them may be neighbours. Sakamoto’s choice of the first-person narrative perspective contributes to the book’s psychological and emotional impact by endowing the narrator’s transmission of that past with an increased sense of immediacy, intimacy, and vividness. Although the story’s conversation revolves around the woman and girl, readers will get the impression that the narrator is speaking directly to them. Through this narrative frame, the story unfolds in a dramatic fashion by weaving the narrator’s experiences with that historical era’s political events in the context of the present time.

In doing so, the story functions as a personal testimonial that bears witness to the historical period and invites people to engage with it on a more personal level, both for the young girl in the story and for the book’s readers. The act of storytelling, itself, becomes an empowering and recuperative act for Shizue, who comes to signify for other Japanese Canadians with histories like hers. Bearing witness to that era ensures that those experiences are heard by others, which becomes imperative for acknowledging that past and ensuring that it is not forgotten. Furthermore, the book prompts readers to question what they know about the past, reflect on how it continues to impact people in the present, and consider how they will use their new knowledge. However, the book does well to avoid lecturing its readers who will naturally gravitate towards these questions when they become immersed in the narrative

Sakamoto’s poetic text incorporates water as an extended metaphor with multiple levels of meaning, thereby elevating his book’s aesthetic qualities and providing a satisfying structural unity between its text and images that is sustained for the entire story. At the beginning, Shizue mentions that she is slowly losing her mental capacity and likens the transient quality of water with the inevitable fading of memories that she will experience over time. As the rest of Shizue’s experiences unfold, suggestive textual passages evoke water as an eternal and unstoppable entity that will forge ahead resolutely, regardless of the obstacles that it may encounter. Water comes to signify development and change at both an individual and collective level. Shizue’s father mentions his affinity for water when he goes fishing and affirms that Shizue will find her own path as she grows up. Despite the hardships that Shizue’s family experiences during and after the war, Shizue becomes inspired to make a difference when she observes the public protest towards the government’s deportation bill. Here, the story evokes the power of water by referring to the collective impact of Shizue’s and others’ efforts to instigate change. Each person’s contributions are likened to individual ripples that collectively can inspire hope and make a significant impact.

Rachel Wada’s illustrations increase the book’s emotional impact for readers by complementing important plot moments and themes. For example, the Japanese internment’s injustice is emphasized through a series of illustrations that are suggestive of a realist or documentary style. At the same time, these illustrations are not simply stylized or objective representations of that past. Wada’s use of shading and multiple gradations of colour and texture capture that time period’s oppressive circumstances for Japanese Canadians. One particularly poignant and powerful illustration depicts the interior of a Japanese internment camp where the narrator’s family and others are imprisoned. The illustration’s foreground has a huge close-up of the barbed wire, behind which are the darkened, unidentifiable shadows of Japanese Canadians who toil in manual labour while their captors look on. These visual effects convey a sense of depersonalization and inhumanity as they are represented as nameless and indistinguishable individuals.

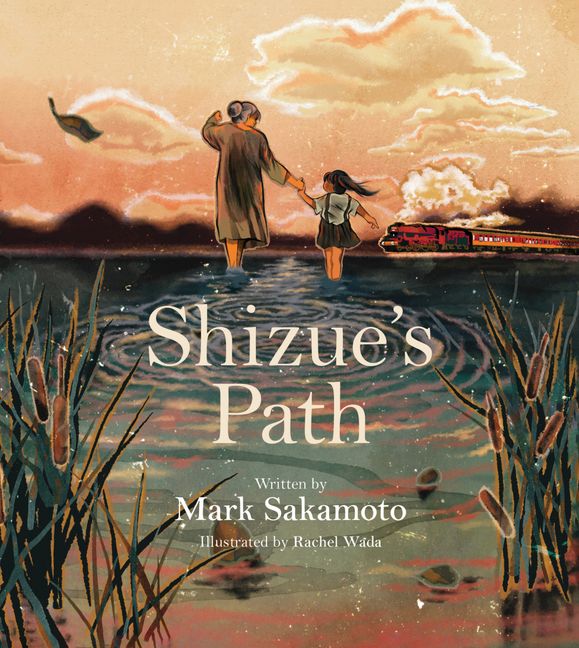

In terms of the book’s themes, Wada evokes the metaphor of water in various illustrations by incorporating numerous gradations of blue that subtly meld with other colours. These create an all-encompassing visual effect that enwraps the entire narrative and shapes its meaning through the lens of water as a metaphor. When Shizue speaks about water in both literal and metaphorical terms, she mentions the water’s persistence and power in finding an inevitable path forward, which can be likened to people who attempt to chart their own path successfully. These musings are rendered to dramatic effect by Wada’s accompanying two-page illustration. Shizue and the young girl are situated at the lower part of the illustration where they are surrounded by water. Shizue watches on while her new, young friend charges ahead towards an atmosphere of deepening darkness that is encircled by water. Bold lines and flashes of colour evoke the water’s omnipresence and render it as a living and active entity.

The final image showing the elderly woman holding the hand of her young listener draws attention to connection that has developed between these two people—both literally in terms of their physical contact as well as metaphorically through the narrator’s transmittal of her story from one generation to the next. Her listener signifies that transference of knowledge and suggests that this is only the beginning of the journey that will unfold. As their faces are not shown, readers can readily identify with the young person by imagining themselves in her place.

Although the publisher’s website indicates that Shizue’s Path can be read by children ages five to eight, this book would be more suitable for older readers, including adults. A full appreciation of the book depends on having a certain level of historical knowledge and capacity for empathy and critical thought that younger readers may lack. Readers under the age of eight could comprehend the story on a general level, but they will not fully grasp the story’s intricacies, references to specific political developments, and historical significance. Without adult assistance, the book’s narrative style and language also does not lend itself to easy comprehension for readers from this age group. Parents or teachers can provide additional context and define unfamiliar words that may be challenging, but the younger readers lack of knowledge and level of emotional maturity will make it challenging for them to appreciate the story in the same manner as older readers. For example, adult readers will comprehend and identify with Shizue’s father and his imparting of wisdom to his daughter, something which young readers could not relate to due to their lack of life experience.

Shizue’s Path would be a valuable contribution to academic, public, and school libraries that seek to increase their representation of Asian experiences in Canada and, more specifically, underrepresented viewpoints about the war’s impact on people’s daily lives. As a powerful testimonial to Japanese Canadians’ historical experiences, Sakamoto’s book signals the importance of having ongoing conversations about that past and its continuing relevance for understanding Canada’s evolution and its current challenges. Shizue’s sharing of her experiences with the young girl signifies the importance of remembering that past so that the same mistakes will not be repeated. In the classroom, teachers could include this book within a unit about Asian Canadian histories and use it to initiate discussions about what it means for someone to narrate their own life and how they determine what is significant to include in that narration. Alternatively, students could consider the book’s aesthetic qualities and reflect on how it leverages the picture book genre to provide a personal representation of that historical era. The book also has a historical timeline that readers can consult for more information. For older students, teachers could approach the book as a fictional autobiographical text and stimulate conversation about what it means to narrate one’s life, particularly when it involves recalling traumatic experiences that have not only impacted them individually but also their community.

A lawyer by training, Mark Sakamoto has had a varied career prior to becoming a writer. Beginning his professional career in live music, he subsequently worked in law, broadcasting, and politics. Currently, he is an entrepreneur and investor in digital heath and digital media. He sits on the Giller Foundation’s board of directors and resides with his family in Toronto.

Illustrator Rachel Wada is based in Vancouver and was raised between Hong Kong and Japan. Amalgamating cultural influences and techniques that reflect her Asian heritage, her visual style combines traditional mediums such as calligraphy, watercolour, ink and brushwork with digital ones. She is a graduate from Emily Carr University and has illustrated for books, magazines, online media, and advertising.

Huai-Yang Lim has a degree in Library and Information Studies. He enjoys reading, reviewing, and writing children’s literature in his spare time.