| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXIV Number 35. . . .May 11, 2018

|

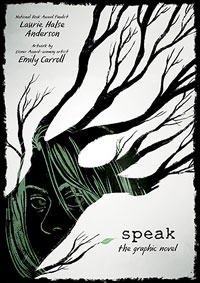

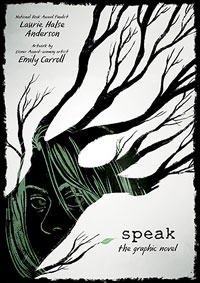

Speak: The Graphic Novel.

Laurie Halse Anderson. Artwork by Emily Carroll.

New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux (Distributed in Canada by Raincoast Books), 2018.

384 pp., hardcover, $25.99.

ISBN 978-0-374-30028-9.

Grades 8 and up / Ages 13 and up.

Review by Charlotte Duggan.

**** /4

Reviewed from Advance Reading Copy.

|

| |

|

excerpt:

IT FOUND ME

800 girls in this school and he finds me. Whispers to me. I can smell him and I want to THROW UP. The stink of him…

One night at an end-of-summer party, 14-year-old Melinda Sordino is raped by a high school senior. Melinda does what she’s been taught to do when something bad happens: she calls 911.

But on the first day of school, the point at which the novel begins, we see that Melinda has become a social pariah, physically and emotionally abused by her classmates because she called the cops and ruined the party. It isn’t until the middle of the novel that we piece together the whole story. In an authentic rendering of victim behavior, we realize that Melinda has not disclosed the sexual assault to anyone. Instead, she has shut down, barely speaks at all, and is on her way to a lonely, angry hell where only she knows the truth.

It is this gritty realism that made the original version of Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak a worldwide success. The #MeToo movement and even the election of Donald Trump have moved rape culture and sexual assault to the front of the conversation, and many excellent YA novels now explore this theme. But in 1999, when Speak was first published, it was cutting edge literature, making its way to the top of both high school recommended reading lists and banned book lists. This year, Anderson has teamed up with artist Emily Carroll to create a stunning graphic novel version of Speak.

Anderson has boiled the original text down to bare necessity, making room for Carroll’s evocative black, white and grey images to fill in the details. Carroll depicts Melinda as haunted and hunted. She is hunched over with deep, dark shadows under fear-filled eyes. The font size often mirrors Melinda’s pain, at times screaming her distress in extra large font; at other times a tiny, thin script whispers her fears. The panels are irregularly shaped and without pattern, again mirroring Melinda’s disorganized, emotional state as she spirals towards an inevitable crisis.

Like the original novel, the graphic novel is divided into four sections surrounding the school’s four grading terms. This organization suits the content perfectly because most of the action, most of Melinda’s torment, happens at school. From the school bus ride– where Melinda is pelted with balled up paper, to the opening day assembly where the words I HATE YOU float across the auditorium to Melinda via her former best friend Rachel, to the nightmare of the cafeteria, Melinda endures relentless abuse all because she called the police the night of the party.

As Anderson herself observes in the author notes, a graphic version of the story is a natural fit given the role art plays in Melinda’s story. Despite her frustration at being assigned a word that she will spend the year turning into art: “you’ll sculpt it, papier mache it, carve it, paint it, explore it in every way possible until you figure out how to make it say something, express an emotion”, the art room is the only classroom where Melinda feels any sense of connection.

Melinda has been assigned the word “tree”. Her struggle to create an authentic tree follows her emotional battle to stay above water. Images of trees and branches weave through the text in the graphic novel version.

While the abuse and torment Melinda suffers at the hands of her fellow classmates is upsetting, it is her internal struggle to cope with the rape that obsesses Melinda. She is filled with self-loathing, saying, “I have the wrong hair, the wrong clothes and the wrong attitude”. She is alienated even from herself: “It’s getting harder to talk. My throat is always sore, my lips raw, like I have spastic laryngitis. I know I’m messed up. I want to confess everything hand over the guilt and mistake and anger to SOMEONE ELSE. There is a beast in my gut, scraping away at the inside of my ribs.”

Very powerful images accompany the very upsetting text. After one nasty verbal assault, Melinda flees to the washroom. “The salt in my tears feels good when it stings my lips. I wash my face until there is nothing left of it. No eyes, no nose…no mouth. A slick nothing.” Carroll’s images of a face scrubbed clean of all physical features are sickening.

Anderson has created a very likeable character in Melinda. The assault may have turned her into an outcast, but it’s easy to tell by her wry comments about school and family life that she is a smart, funny girl. Take her observation that the Merryweather cheerleaders must be a miracle - “How else could they sleep with the football team on Saturday and be reincarnated as virginal goddesses every Monday?”

Things get much worse for Melinda when she spots her attacker at school. Andy Evans - Melinda calls him “IT” - attends Merryweather. She says, “It is my nightmare. I can’t wake up. I need to hide.” But Andy is everywhere, blowing in her ear, winking at her, mocking her. Carroll depicts him as nondescript, almost benign. Meanwhile stark white line drawings of rabbits on pitch-black pages effectively represent Melinda’s terror. Then one horrible day, Melinda learns that he is dating Rachel.

The story jolts towards a shocking, violent climax where Andy attacks Melinda a second time, visually transforming into the monster Melinda knows he is. Carroll ramps up the terror by reducing the number of panels per page, and spreading the attack over many pages. A single punch and scream cover two pages, maximizing the impact and the horror.

The resolution follows quickly and satisfactorily. Sitting under the tree where she was raped so many months ago, Melinda realizes that a “small, clean seed-of-me is waking up”. And, although the final page is solid black, Melinda says one crucial thing: “Let me tell you about it”.

Speak is an important, groundbreaking novel, and the graphic novel version makes the story that much more accessible. This is a must-have addition to all libraries that serve young adults.

Highly Recommended.

Charlotte Duggan is a teacher-librarian in Winnipeg, MB.

© CM Association

CC BY-NC-ND

Hosted by:

University of Manitoba

ISSN 1201-9364

|

This Creative Commons license allows you to download the review and share it with others as long as you credit the CM Association. You cannot change the review in any way or use it commercially.

Commercial use is available through a contract with the CM Association. This Creative Commons license allows publishers whose works are being reviewed to download and share said CM reviews provided you credit the CM Association. |

Next Review | Table of Contents for This Issue - May 11, 2018.

CM Home | Back Issues | Search | CM Archive | Profiles Archive

|