| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XXIV Number 26. . . . March 9, 2018

excerpt:

Jafar is an Indonesian child labourer. For three years, he’s been sweeping the endless wood dust that begrimes the furniture factory in which he works, sanding cheap wooden chairs until his fingers have become hard and callused, enduring continual verbal abuse and threats of punishment from Boss, the factory’s overseer. The work is monotonous, but Jafar’s mind is engaged and lively; a stray sunbeam illuminates the wood dust that fills the air, and he thinks “I’m in a gold factory.” (p. 12) In that light, the expensive chairs look like thrones, and as he looks at the many different chairs manufactured, he wonders “Who would sit on his chairs?” (p. 13) Jafar has a secret: after work, he goes to a school for working children where he has learned to read and, more importantly, to write. At the end of “The Singing Chair”, using a metal nail, he inscribes a six-word, two-line poem onto the underside of the seat of a chair on which he has worked. As the chair is loaded onto a delivery truck, he hears it singing the words of his poem:

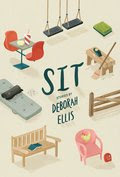

“The Singing Chair” is the first story in Sit, a collection of 11 short stories by Deborah Ellis. In each story, a chair of some type becomes symbolic, both of “being here” (living in the current situation), and of “being there” (escaping) For seven-year-old Macie in “The Time-out Chair”, a dinosaur-embellished, pink plastic chair from her toddler days is a source of punishment. Not only does Mommy enjoy putting her daughter in the time-out chair, allegedly because of Macie’s ongoing disobedience, but she also revels in the humilitating control she exerts over her child. However, Macie knows how to escape, whether through reading books or via daydreams. One afternoon, when her mommy has friends over, Macie’s 14-minute time-out passes quickly in a daydream of a tree-house where her friends are the birds and animals of the surrounding forest. Emboldened by the freedom of her thoughts, in an act of daring, she turns off the kitchen timer that ticks down the minutes of her time-out. “In her head, then, she floats up out of her punishment chair, heads deep into her forest house and gives herself a well-deserved time-out.” (p. 31) In “The Question Chair”, Gretchen sneaks away from her classmates while visiting a former Nazi concentration camp in Poland. Even though she knows one is not supposed to sit on or touch things in a museum, she feels compelled to sit on a toilet in the camp – a latrine, “a trough with holes” – and tries to imagine what it would have been like to be a prisoner, “given no peace even in this most basic and universal of human moments.” (p. 33) She is German, not Jewish. However, sitting on that wooden toilet hole sparks a series of profoundly disturbing questions about the wilful ignorance of her countrymen during war-time, about her middle-class professional parents and the likelihood that they would have supported the Nazis, and most of all, about herself. Adolescence is a time to question, and at the end of her story, she questions who she would have been, during that time, and what she believes now. She is not complacent. “Questions, she thought, I’ll keep asking questions.” (p. 45) Gretchen is obsessed with what she doesn’t know. In “The Knowing Chair”, 10-year-old Barry, sitting on a red metal food court chair, has an innate sense that something isn’t quite right with tonight’s family outing. They are out on a school night, and instead of the usual protracted discussion about what they’ll eat, his parents allow him and his seven-year-old sister, Sue, to choose their own meals before they all go to a movie. The kids make their choices and then, as Barry settles down to his meal and Sue commands their parents’ total attention, he “indulge[s] in his favorite hobby – watching people.” (p. 49) In the midst of his musings, his sister points out a food truck, asking if they’re all going on a trip. The Trip is an idea that had taken on a mythic quality in that family – a year off from school, living on the road in an old van – and Barry has thought a great deal about the freedom it promised. While his sister prattles on and on about what they’d see and do, Barry is distracted by another family, a couple who are arguing and have clearly upset their little boy. Barry goes over to help the little guy, but as he leaves them, he looks up at one of the food court’s overhead mirrors, and catches sight of another arguing couple. The couple is his parents. Then, he knows why his parents have taken them out for supper at the mall on a school night: it’s a shameless bribe, an attempt to prevent their children from making a scene in public as his parents announce their decision to split up. Later in the short story collection, the focus shifts to Sue. Sitting on a swing in a playground, she listens to her mom and Barry argue. “Sue really wanted to swing. She wanted to pump her legs and push with her back and make the swing move high and fast so that she could feel the air whoosh around her.” (p. 121) Their mother has positioned herself so that neither Barry nor Sue can make those swings move. That playground swing is “The War Chair” of the story’s title, and their mother is a roadblock, provoking a minor skirmish in the ongoing conflict between the two parents. Soon, it’s time to head across the street to Family Mediation and Supervised Visitation Service. Sue really doesn’t want to go inside, but prior to their first custodial visit with their dad since he moved out, they have to meet with a social worker, Ms. Dira. Before the meeting begins, all three of them hear the parents raging at each other outside in the parking lot. Ms. Dira grew up in a family where her parents fought all the time, and she understands Barry and Sue’s situation. Reminding the two that “this is their war, not yours. This their choice, not yours” (p. 128), she gives them some coping strategies. And then, the meeting is over, their dad arrives and they get into his car, where Sue sits, holding her brother’s hand tightly. Separation and divorce is one way in which a child’s family undergoes profound change. Death is another. In “The Plain Chair”, the story begins in the early hours before dawn, with Jed on a “plain wood fence, comfortable for sitting” (p. 58) outside a schoolyard on an agricultural community – perhaps Amish, Hutterite, or Old Order Mennonite. Jed’s father has been dead for years, and now, there is just his mother and himself. His little sister Melinda has been the victim of an unspeakable tragedy, one which he witnessed. A man walked into their one-room schoolhouse, randomly chose students, ordered them to the chalkboard at front of the class, and then shot them and their teacher. The school was a simple, plain building, “not like those fancy schools the English children went to in town, with inside bathrooms and many classrooms filled with shelves of books and rows of computers.” (p. 60) The men of this community “put [their] grief to work” (p. 65), dismantling the school, planting shrubs and flowers into the smoothed-over ground where the building once stood. Jed decided that he would help the men with this grief-work, and, tomorrow, he would help his mother by taking on his sister’s chores. There’s no day off for Jed, but in “The Day-Off Chair” 10-year-old Bea takes a break. Like Barry and Sue, her family life is troubled; both parents are alcoholics, and her mother “could get angry at anything at any moment. . . . She could drive and hit at the same time.” (p. 73) That morning, after her mother drops her at school, Bea decides that she needs some “me” time and heads for downtown, settling herself on a bench on Oak Street, the day-off chair of that story. Suddenly, her quiet time is interrupted by a little boy shouting “Mom!” His mother is talking to someone, and he takes the opportunity of her inattention to hide himself behind a decorative rock. As the boy’s mom walks towards the rock, Bea imagines the punishment he might face when he jumps out to surprise his mother. Undoubtedly, Bea is drawing on her experience of her mother’s anger, and Bea decides to tackle the mom when she tries to hit her son. But, when the boy jumps out and yells “Surprise” and Bea calls out “Don’t hit him!”, all that happens is that the mom says “You got me!” (p. 76) gives her son a hug, and the two set off down the street, laughing. Bea is shaken, starts to cry, and decides to return to school, rather than continue her day off. Just as Bea wanted to save the little boy from certain punishment, in “The Glowing Chair”, Miyuki wants to save her mother’s donkey, Hisa. Sitting on a tatami mat in an evacuation center set up in the aftermath of the explosions at the Fukushima nuclear plant, she is arguing with her father about going back to their home to check on the animal. The veterinary clinic at which her mother worked was swept away in the tsunami, and now, 12-year-old Miyuki, her brother and father are waiting it out in a former high school gymnasium. Her brother is dismissive of her concern: “She’s an animal. She’s down here.” He put his hand two feet from the floor. “Man is up here.” He reached for the sky. “Girls are down here.” He put his hand flat to the floor and squished it down, trying to go even lower. . . . “you care about that donkey so much, go and get it. Stop talking about it. All you do is talk.” (p .82) Until now, Miyuki has always been dutiful and uncomplaining, but sitting on the floor of that gym, she makes a decision. Filling her schoolbag with water and food, Miyuki slips out and walks the 13 kilometers to their village, which lies within the radiation zone. Once there, she finds the donkey crouched in its pen. On the return trip, Hisa and Miyuki are joined by four little dogs, and when they arrive at the evacuation centre, she is met with cheers, and the dogs leap into the arms of their owners. Yes, she needs to undergo radiation decontamination, but she glows with pride at her new identity. She is her mother’s daughter, someone who challenges the rules, and is no longer silent Miyuki, but “Nariko”, a name that means “thunder”. Breaking the rules doesn’t always turn out well. In “The Freedom Chair”, while standing in the prison chow line, Mike asks why inmates are served applesauce instead of apples. “We’re in apple country,” . . . It’s harvest time. Real apples are cheap right now.” (p. 94) That question, along with a series of other minor offences, earns him 72 days in Administrative Segregation (Ad Seg), a euphemism for solitary confinement. Other than the floor of his cell, the only place to sit is a concrete slab of a bed covered with a thin rubber mattress and an equally thin blanket. Surviving that type of incarceration takes real mental courage. On Day Five of his term, Mike starts losing hope and tells the inmate who brings him his meal that he doesn’t think that he’s going to survive the ordeal. The inmate gives him advice: “Use what you have. Free your head.” (p. 98) Helped occasionally by messages, and unexpected gifts which appear on his food tray – a packet of ketchup, a mini chocolate bar, a book – Mike thinks about other famous prisoners and decides that he will survive. Finally, when he’s out of Seg, he goes to work in the prison kitchen, and pays forward goodness in the same manner that he received it. In Ad Seg, Mike never saw darkness; the lights were on, 24/7. In “The Hiding Chair”, Noosala never sees the sun. As the story begins, she sits on a plastic mat (not the beautiful carpets of her Afghan homeland), hiding in an Uzbekistan apartment along with 18 other refugees. Heavy drapes cover the windows of the rooms in which they live, and their landlord warns them repeatedly never to open the drapes because “there are police right outside, watching for illegals like you. If they see you, they’ll ship you right back to the Taliban.” (p. 111) Eight months have passed since their arrival, food is increasingly scarce and soon, half the people in the flat are sick. Noosala helps to take care of the ill, but finally, her patience gives out, and she decides that she’ll take her chances: “I want to live.” (p. 117) Defiantly, she opens the drapes. Across the street are apartment buildings and kids playing. No police station. She cries for help, people arrive and are shocked at the condition of those still alive in that room. A policeman comes, calls for assistance, and in the midst of people coming and going, Noosla escapes, breathing the fresh air of freedom. In “The Hope Chair”, the final story in the collection, Jafar is not sitting. He has left work for the day and is running to school through the sights and sounds of the city in which he lives. Once there, he stops to greet his teacher politely, has a quick wash, a snack, and then, he sits on a green grass carpet, ready to listen, and to write stories. “Jafar sings stories out to the world, and the world, in turn, sings back to him.” (p. 139) Although Sit is only 139 pages long, it packs a real punch. All of the children in the book’s 11 stories face difficult life situations: poverty, imprisonment, war-time displacement, family break-up, shame, alcoholism, abusive parents. Yet, none allows himself or herself to feel like a victim for very long, and all find ways to move forward, to make choices which will change their lives in some way, big or small. Ranging in age from elementary to high school, each character speaks in a voice that is authentic and memorable. In telling their stories, Deborah Ellis also highlights issues faced by children throughout the world today: child labour, the plight of young offenders, the effects of war, violence in schools, family breakdown. Sit is a powerful collection of stories, and although the intended audience is the middle-school reader, it can just as easily be read and enjoyed by high school students. The stories are short, and their accessibility makes this collection an excellent choice for less-than able and reluctant readers in both middle and high school. Sit is an obvious choice for school library fiction collections, but I see many of the stories having a place in content-area subjects: Psychology and Sociology, World Issues, Family Studies, and obviously, English/Language Arts. I think that it’s hard not to find at least one story with which students can find a personal connection. So, find your “Reading Chair”, sit down and lose yourself in the power of story. Highly Recommended. A retired teacher-librarian, Joanne Peters lives in Winnipeg, MB.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- March 9, 2018. |