| ________________

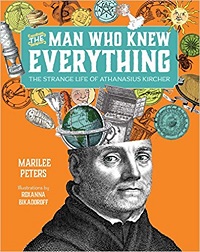

CM . . . . Volume XXIV Number 18. . . . January 12, 2017

excerpt:

Athanasius Kircher was born in a German village in 1602. At the age of 16, unable to pay university fees, he decided to become a Jesuit. Seventeenth century Europe was in turmoil as the Protestant Reformation and power struggles amongst the elites gave rise to the Thirty Years’ War. Kircher escaped to Rome where he got a job teaching mathematics and pursued his own studies of the natural world. He lived during the Scientific Revolution when scholars questioned traditional explanations and developed the scientific method of observation and experimentation. It was a dangerous time to challenge ideas espoused by the Church. Scientists could be declared heretics, put on trial, and even executed. Peters’ informed text and Bikadoroff’s colourful, imaginative, and detailed illustrations make for fascinating reading and enjoyment. Many of the illustrations resemble hand-coloured seventeenth century etchings. Anyone with a curious mind will delight in the adventures and exploits of Kircher and the discovery of a few of this Renaissance man’s theories. Peters writes:

Obviously, Kircher did not know everything, and many of his ideas were far from accurate. Peters pays considerable attention to Kircher’s quest to understand the interior of the earth which led to his dangerous descent into active Mount Vesuvius. He wrote to other scientists and priests who shared rock samples, fossils and other discoveries with him. His growing collection of oddities became so numerous that he put them on display in Rome, alongside his inventions, and the Kircherian Museum was born. It enjoyed status as a tourist attraction. After a decade of study and writing, he published The Underground World, an 800 page tome that is one of the first books on geology. Four of Kircher’s theories about how the world is constructed are presented and validated or debunked in brief explanations. Later in the book, Peters presents eight more of Kircher’s theories, most of which were very inaccurate, but a few were much closer to what modern day scholars would call truth. Following Kircher’s death in 1680, his museum was disassembled, and his ideas fell out of favour as scientists began to specialize in distinct fields and continued to share their knowledge with other scholars. Renewed interest in Kircher can be traced to the opening of the unusual Museum of the Jurassic in Los Angeles in 1988. A chronology, map of Europe and the Mediterranean world showing Kircher’s travels, further reading, sources and an index round out the features of the book. Peters explains many terms, such as heresy, in the text, but a glossary would have been a very welcome addition to the book. Terms like censor and Inquisition could use more explanation. A minor quibble is the number of Germans killed during the Thirty Years’ War. Peters states that more than a third of the population died, but Richard Holmes and Toby McLeod writing in the Oxford Companion to Military History (online version 2004) suggest that fifteen to twenty percent of the population died but many others were displaced. The Man Who Knew Everything is guaranteed to be a hit with students and curious adults alike. Highly Recommended. Val Ken Lem is a curious librarian at Ryerson University in Toronto, ON.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- January 12, 2018. |