| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXIII Number 4. . . .September 30, 2016

excerpt:

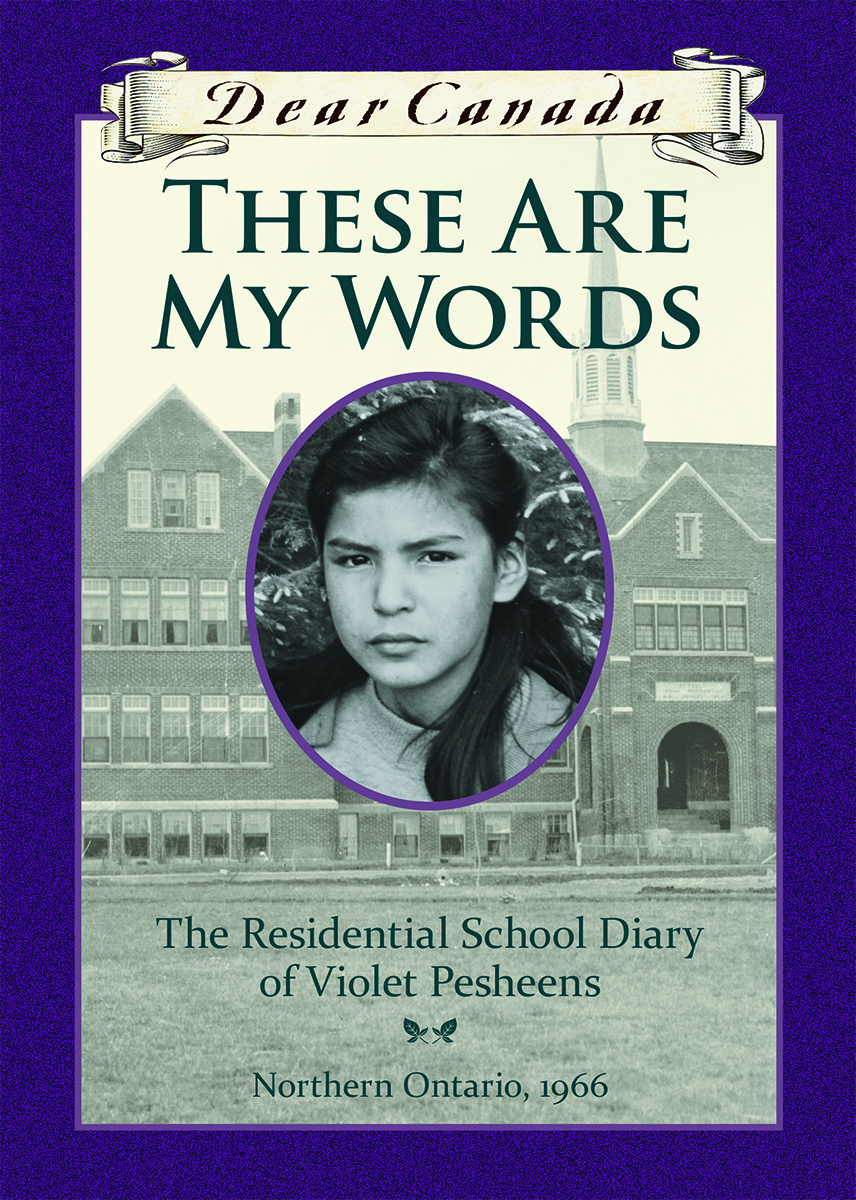

Violet Pesheens, the narrator-protagonist of These Are My Words, appeared in a short story, "Winter with Grandma", in A Time for Giving: Ten Tales of Christmas. In that story, 12-year old Violet's life involved attending the village school in the Northern Ontario railway settlement, Flint Lake. She also helped her grandmother ice-fish and cut wood. Her only worries had to do with the number of unwanted dogs in town and the stories about residential school brought home by older children when they returned for Christmas and Easter. Ironically, Violet's story stands out in a Christmas story collection as the only one not about Christmas. In the largely First Nations community, Christmas was not widely celebrated. In the fall of 1966, 14-year-old Violet and seven other children leave Flint Lake for school in the city. These Are My Words presents the story of that year through Violet's eyes, starting with the tearful goodbyes as they board the "Train of Tears" (an allusion to the "Trail of Tears", the 1838 forced relocation of the Cherokee nation in the United States, a 1,000 mile forced march in winter, on which a quarter of the Cherokee died.) In These Are My Words, the First Nations children heading for the city survive their trip, but it is clear from Violet's account that it was dangerous and poorly planned by Indian Affairs. The diary form and the choice of a child narrator are good devices for shedding light on social issues. A young person's innocent observations and interpretations expose flaws and evils in the milieu being depicted. Like Scout, in To Kill a Mockingbird, whose naivete draws attention to the class hierarchy and racism of the American South in the 1930s, Violet's perspective, as a First Nations child from a hinterland community, shows the iniquities of the residential school system, including the emotional toll of wresting children from their family, culture and community. Prior to the 1960s, children in residential schools usually lived and went to school in the same building. In the 1960s, students living in residential schools were integrated into urban schools, taking classes with the general population of students. This is the case with Violet. Older students, like her friend Emma, board with families. Of the residential school, Violet writes: "It reminds me of soldiers I once saw in a book - all looking the same and all doing the same things at the same time. Even our dorm looks like an army's barracks." Indeed, the initiation and regimentation of school life was shocking. On arriving, children were given an overwhelming list of rules to remember, including the "English only" rule; students were forbidden to speak their own languages and would be punished if they did. Violet's diary, a gift from her grandmother, is confiscated, but she starts a new, secret one on folded paper hidden in her school books. She is given a harsh de-lousing shampoo, though she doesn't have lice, and then a standard "Dutch boy" haircut, a uniform, and a number. Mail is limited to letters from family and is censored and sometimes withheld. "We are not allowed to say anything about the residential school when we write home," Violet notes. No one tries to make the children feel at home; indeed, the adults are mean. When Violet's grandmother telephones her long distance from the village store, the call is put through, but when a staff member standing by hears Grandma address Violet in the Anishnabe language, he cuts off the call. On the first day of school, Violet follows three other girls who enter a park across from the city school. The four of them huddle in the base of a hollowed-out tree until it is time to go back to the residential school for lunch. Their absence has been noted, and they are called before the residential school principal and scolded for "playing hooky", an expression unfamiliar to Violet. At the city school, Violet spends her recesses alone, standing by the door where "no one bothers [her.]" Only one teacher ever asks about her life at home. Violet is not a whiner. Her diary entries have the tone of someone bravely trying to cope with rules and expectations. By October, however, she writes that she feels anger "like a burning pain in my chest." By November she writes: I am feeling like I am stuck in a very long mourning period where you cannot start crying for the person who died and you have to wait for the right time. My heart and soul are starting to hurt. From her reminiscences, and from the letters from her grandma at Flint Lake, and from her mother on a reserve (where she lives with Violet's stepfather and their two children) the reader realizes that, at home, Violet is part of a friendly, hospitable culture, with a balance of indoor and outdoor activities and adults with strong organizational abilities and initiative. Violet is never assimilated. While she likes some aspects of residential school life, such as new foods, television, and dental and eye care, she is fundamentally uninterested in the many holidays (ranging from Thanksgiving to Groundhog Day) and the Christian religious services. The simple act of keeping a diary is subversive. With the help of a kindly part-time supervisor, she contravenes the mail rules. Afraid of forgetting the Anishnabe names of things, she begins keeping word lists. From the other girls at the residential school, she learns disturbing things which further alienate her from white culture. On their way through a wooded area from the residential school to attend services at a small church, they pass a place with "boulders jutting up from the ground" (a cemetery). An older girl tells Violet and the new girls that residential school children were buried there, and that it is their duty to tell new girls about that place. She also hears an older girl say, of an Indian Affairs doctor, that he "touched her in places that she didn't think had anything to do with a medical check-up." On three occasions, there are threats to Violet's personal safety. One is quoted in the excerpt at the beginning of this review. As well, while walking home from the city school to the residential school, Violet is approached by a man in a car who invites her for a ride. She runs and catches up with the other girls who tell her that, if it happens again to take down the licence number and note the colour of the car, "so the police have something to go on if anything happens to you.” In another incident, the candy vendor at the park tells Violet that if she will come back at 5 p.m. he will give her a chocolate bar. "I didn't like the way he was looking at me...from my feet to my head," she writes. "I don't think I will be going there again." At the end, author Ruby Slipperjack presents a brief history of the residential schools in Canada and includes photographs of children at these schools and a map of Canada showing where they were located. Slipperjack's biographical note shows her unique qualifications to write this novel. Born in the Whitewater Lake area of Northern Ontario, she attended a one-room Indian day school, a residential school, an urban school, and Lakehead University, graduating with a B.A. in History and a Masters in Education. Holding a Ph.D. in Educational Studies from the University of Western Ontario, she is a tenured professor and department chair of Lakehead University's Indigenous Learning Department. She is the author of five other novels. Given the harshness of Violet's experiences, readers do not expect that These Are My Words will end in a positive way, but it does, thanks to a decision made by her family. My only complaint is with the six page epilogue in which Violet's life is summarized until she reaches age twenty. This material deserves to be expanded into another novel so that readers can spend more time in the company of sensitive, perceptive Violet. Highly Recommended. Ruth Latta, an author, lives in Ottawa, ON. For more information about Ruth Latta's books, visit her books blog at http://ruthlattabooks.blogspot.com

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue - September 30, 2016

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |