| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXIII Number 30. . . .April 14, 2017

excerpt:

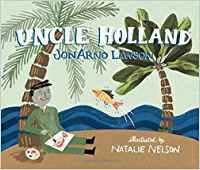

When selecting literature, teachers and teacher librarians often consider the need to find stories and information relevant to the lived realities, hopes, and dreams of their students. Because such material is sometimes difficult to find, I am particularly excited about JonArno Lawson’s and Natalie Nelson’s Uncle Holland. Not a typical find, this is a fictionalized biography informed by a period in the life of Lawson’s real uncle. In this account, Holland is the eldest of three sons parented by Palmer and Ella. When the story opens, Holland is shown as a smiling, smug and perhaps a bit too self satisfied young man. We quickly learn that Holland frequently “stole things”. He gravitated toward “stuff that was pretty” and he “couldn’t help stuffing that pretty stuff into his pockets”. This serial stealer bumps up against reality after his thirty seventh time of being caught by the police. He is given an ultimatum: go to jail or join the army. Holland chooses the army and is transformed by the experience. Most children from Grade Two and up will have no difficulty understanding the narrative of Uncle Holland though the focal character is more of an adolescent than a child. Lawson’s accessible language and Nelson’s wry, comical and equally accessible cartoon and mixed media art help to make Holland a sympathetic character that many children will find endearing. Like them, Holland is not perfect; he is imperfect in ways that some, if not many, children can relate to with ease. Similar to Holland, they, too, like stuff that is attractive; stuff that they sometimes want to possess, and control. Their pockets are ideal containers for stuff taken without permission. On page four of the picture book, Nelson depicts a red-faced, stylishly attired Holland looking out slyly, and with some shame, at the reader (as if to say, you caught me) with one hand in his stuffed pocket and the other holding a large vase that he cannot possibly fit into a pocket. Many children, young adults and adults, too, will understand Holland’s interesting but anti social proclivity and predicament. He is not stealing out of material necessity; he is perhaps stealing—taking stuff—out of a compelling psychological and emotional need to do so. That too will be understandable by many. For those children, young adults, and adults who are recurrent pilferers, relatability to Holland may come from living in geographic locations characterized by the omnipresence of materialism and acquisitiveness. These are locations in which people are surrounded by so much “stuff” and messages pushing acquisition that they are propelled to take and get what they want—sometimes with money stolen from others (in Holland’s case, from his brothers Jimmy and Ivan). Because Holland’s behavior is not so atypical (in real life and in movies for instance), readers will comprehend the strong feeling of power and invincibility that comes after a successful theft and that pushes pilferers into periods of perpetual theft. A familiar part of the discourse in such narratives in life and in film, and that is needed in children’s literature (to quell anti social activity and encourage pro social ones) is that perpetrators’ behavior eventually catches up with them through the intervention of the law. In Uncle Holland, this intervention is explicitly emphasized by the pointing finger and admonishing words of the policeman on page five when Holland is caught stealing for the “thirty seventh time.” On page six, those same words are repeated without quotation, in a different typography—big, bold letters: “Holland Lawson, Either You Go To Jail OR You Join The ARMY. It’s Up To You.” Furthermore, the word “you” is underlined to show its force, power and unequivocality: Holland must accept full responsibility for his actions. The law—the authority of the state—the omniscient narrative voice steps away from narration to make a declaration—and comes down hard on Holland. This is his moment of reckoning. He alone must choose between punishment (jail) or penalty/penance (army—service to the state). By choosing the latter, Holland causes heart break (his parents’) and tears (his younger brothers’) and is not immune to their reactions. Nonetheless, his seemingly passive, resigned, and lost father decides “to spend the rest of his life watching fish swim around in his fish tank”—seeing them as a safer bet against disappointment than Holland. At this stage in the narrative arc, Holland’s mother intervenes; she is seen comforting her husband by placing a hand across his back and by reminding him of the good in Holland and to keep a balanced perspective. She tells her husband that Holland “…may be a thief, but he’s never been a liar.” The mother’s wise call for a balanced and compassionate perspective would make an excellent topic for discussion and reflection between teachers and students and/or between youth and adults—parents/caregivers and children. This is a strategy that the author appears to have in mind on page 11. There, the omnipotent/omniscient narrator appears to break down the “fourth wall”, so to speak, and poses a question directly to the reader when he asks, “Now what would you do if you were Holland? Would you go to jail, or join the army?” Furthermore, the author provides proverbial boxes for the reader to check: jail or army (p. 12). Because the foregoing is rich, non contrived fodder for discussion with learners, I would love to be an observer in a classroom where such a discussion—about balance, compassion, ethics and values, about the right thing to do—would take place. Other fertile topics for discussion that emerge from the book are the impacts the changes in location (“a very pretty place far away to the south”) and vocation (being a soldier) have on the behaviour of the focal character: Holland. The change in geographic location from the north, to a beautiful tropical place is in service of the character’s maturation. The army environment exposes Holland to fewer “shiny objects”. The army sends Holland to an environment where he is surrounded by beautiful things in nature (the blue ocean and their waves, palm trees, flowers, beautiful birds and fish) that cannot be picked, stuffed in pockets and remain so. Such beautiful things do not lend themselves to easy acquisition; they decay and die quickly if picked—if taken. So although Holland still has the desire to be acquisitive, to take, to control and possess that which is deemed beautiful (the tropical fish for example), he is positioned to find a new approach, a new way of capturing those things he finds beautiful. Holland finds that new approach in art. Moved to do something to atone for the trouble he caused his parents and siblings—but especially his father—he buys (not steals) a “little paint palette and a block of paper and begins to paint the colourful tropical fish.” Through these actions, we (teachers and caregivers) can help learners perceive and understand the transformation of Holland—from a youthful offender heading for juvenile delinquency—to a maturing, reflective and responsible young adult now much more conscious of the impact of his actions on those who cared for him and whom he wronged. The double page spread on pages 19 and 20 show a smiling and happy Holland on a tropical beach, using his army rifles as an easel for his paper canvas, and also show a line where he hangs his artistic creations that he later sells at the market. Readers will be warmed and inspired to cheer for this dynamic and transformed character when he reaches the point of being able “to send his parents a big wad of cash, along with a beautiful picture of an extraordinary fish” that his father “hung up behind the fish tank.” They will cheer even louder when Holland is able to respond to his father’s forthright question about the money he sent home: “did you earn the money honestly?” In the final epistolary communication in the picture book, Holland reassures his parents that“ [n]ot everything that’s pretty can be stuffed in your pockets!” and that he has learned “how to put pretty things into pictures and sell them instead!” Through these powerful words, children and youth will see the beginning of the second life of Holland: one of remorse for pain caused to loved ones in the past, and the ability of art—the creative process—to reposition and transform. Uncle Holland illustrates how the focal character is positioned to create instead of take and the powerful healing and satisfaction artistic creativity can engender. In addition, this worthwhile picture book demonstrates how a second chance, a new opportunity/beginning in a new place—a new environment—a natural and beautiful one (in this case, the global south)—has the power to provoke and produce positive change interiorly—emotional, psychological, moral, as well as social growth and transformation. A word of caution is warranted at this stage because of the choices given to Holland by the police officer: going to jail or join the army. This was, and is still, a practice meted out to young adult offenders in countries such as the United States*. In Uncle Holland, the choices appear to be equal. But because the army enjoys a status jails do not, and because there might be children of service men and women with careers in the army in classrooms/libraries who might experience discomfort at the equation, teachers, teacher librarians and librarians could consider providing some contextualization and nuance about the options given to the young Holland in the story. Therefore, a sensitive discussion about the choices offered to Holland is needed. The final words of this review goes to Natalie Nelson whose colour palette (measured and controlled as well as sensitively exuberant) is well suited to the historical period of the story (1930s 1940s—a period of crisis and world war), the subjects of the book (stealing and hurting), themes (change, rehabilitation and growth), and tone (redemption). Additionally, the muted colour palette employed for the characters and their narrative settings may be appealing to diverse children in the many multi hued classrooms across North America and in which, I hope Uncle Holland will find a cherished place. Please, make space for this one in your collection. Recommended. Barbara McNeil is an Instructor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina in Regina, SK..

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review | Table of Contents For This Issue - April 14, 2017 |