| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXIII Number 23. . . February 24, 2017

excerpt:

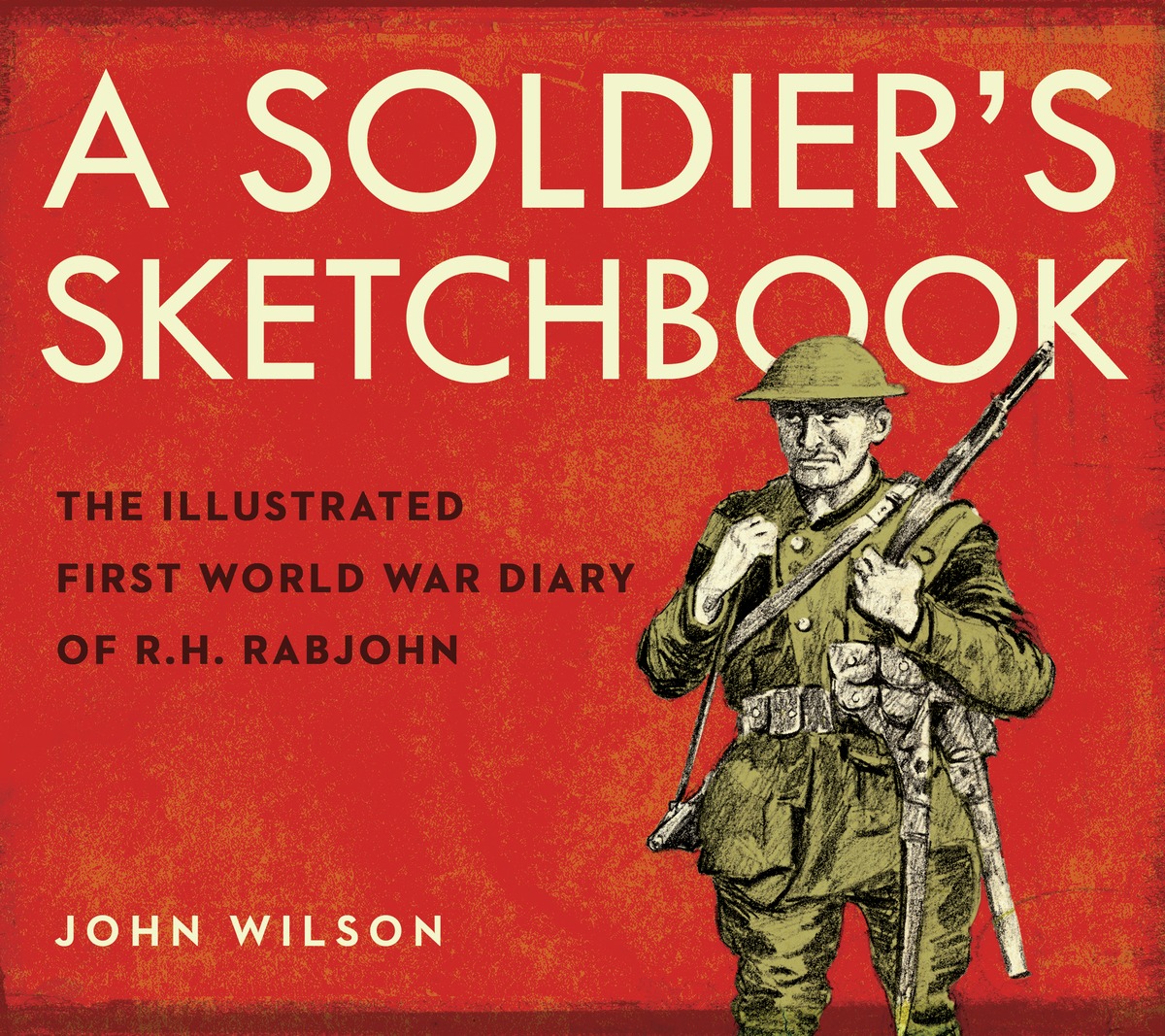

On 22 February 1916, just days after his 18th birthday, Russell Rabjohn of Toronto attested (signed up) and agreed to “serve in the Canadian Over Seas Expeditionary Force”. He listed his occupation as “Illustrating.” His skills as an illustrator gave young Russell a rare opportunity to serve his country and ultimately honour the history of the men who served in the Pioneer Battalions of the CEF (Canadian Expeditionary Force). He was also an excellent diarist. Where many soldier’s diaries are often single rushed lines, Rabjohn, who had a knack for writing, reveals his feelings and the life of the common soldier in a seldom seen light. Author John Wilson learned about Russell Rabjohn’s life story, his war time diaries, illustrations and sketches from one of Rabjohn’s descendants. He knew that soldiers were not normally allowed to take pictures or make drawings of the battlefields, so this was an exceptional historical find. Wilson divides the book into six chronological sections, each corresponding to a specific period in Rabjohn’s life as a soldier: first in Canada and Britain as a recruit; then four sections on life on the Western Front and finally the period he spent in Belgium and Britain waiting impatiently to return to Canada after the war ended. It is to be remembered that this is an incomplete story of the CEF as Rabjohn was not on the Western Front (Belgium and France) when Canadians fought in the Ypres salient and in the Second Battle of Ypres (April 1915 to August 1916)), nor during the Battle of the Somme (September to November 1916) nor at the Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 9 to 12, 1917). The sections are as follows: Training for War: February 1916 to April 1917; Vimy: April to October 1917; In Ypres: October to December 1917; Back to Vimy: January to August 1918; The Last Hundred Days: August to November 1918 and The Long Road Home: November 1918 to March 1919. Each section begins with a BACKGROUND page to provide some historical context. In Vimy: April to October 1917, for example, readers learn about the great battle that has been fought and that new battles are beginning not far away from where Rabjohn is stationed. In the background section of The Last Hundred Days: August to November 1918, readers learn how the German spring offensive had faltered and the Allied forces were now on the attack, hoping to deal a crushing blow to the enemy. Wilson includes one or two short, unobtrusive paragraphs on each page to provide added continuity when there is a gap in Rabjohn’s diary entries. This information is often taken from the battalion’s War Diary which was a day-to-day account of the battalion’s activities and duties, wounded and killed and general conditions on the front. There is approximately a 50/50 ratio of text to Rabjohn’s finely crafted black and white illustrations. These illustrations were re worked by Rabjohn for inclusion in a book on his war experiences, one which was written in the 1970s. The original diaries and drawings, Wilson tells readers, are preserved in the archives of the Canadian War Museum. Unfortunately, there is only one small scan (p. 6) that shows an original diary entry and illustration. More of these scans could have been included and enlarged to draw the reader further into Rabjohn’s story. Young Rabjohn loved drawing, and, when he was 16, he won the Toronto Boy’s Dominion Exhibition Award (1914) for pen and ink drawing. His talent wasn’t recognized by his army superiors until late November 1916 when he was asked to paint and illustrate some training posters. Per Rabjohn’s dairy entry “Officer seemed quite satisfied”, and this led to another six weeks of sketching. Eventually, after training in England, Rabjohn was assigned to the 123rd Pioneer Battalion stationed near Vimy Ridge. The job of a Pioneer Battalion was to support the infantry by repairing trenches, dugouts, and carrying supplies up to the front lines. Rabjohn arrived on the Vimy front a few weeks after the great Canadian battle, but the armies were still engaged in a deadly slogging match. As the war rages on, Rabjohn’s life is immediately in danger, as per his diary entry of 12 May 1917, “...one of the Frizs airplanes gave us a little surprise—passed right over our camp very low, dropped a few bombs, killed two transport fellows, injured about eight. Our machine guns played heavily on him but he got away…” His illustrations graphically depict the destruction and devastation of the land, the bombed out buildings, dead animals, the injured men waiting to be taken to the Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) and the dead awaiting burial. In mid June, Rabjohn was assigned to make sketches of the Canadian trenches, mark out machine gun nests and the battalion camp. He went up to the front to observe and draw what he could see. He was still in danger from shelling, enemy aircraft and “this new [mustard] gas Frizs is using that irritates your skin, as well as [being] deadly if inhaled.” In the summer of 1917, the British and German armies waged a desperate deadly struggle in the six month Battle of Passchendaele (3rd Battle of Ypres) in Belgium. In October, the British Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig called upon the CEF to come help the British in their fight against a highly motivated and well dug in enemy. The Canadians moved out of their billets on Vimy Ridge billets and marched toward the new battlefield. The Battle of Passchendaele is remembered for its deep, glutinous mud and constant rain, as per Rabjohn’s diary entry of 20th and 22nd October 1917, “The mud was terrible—mules stuck, men almost …Impossible to dig more than two feet in the ground for water, as we’re just above sea level. Any trenches there happen to be filled with water. The front line consists of shell holes…” and “…. By the weight of my boots I’m carrying half of Belgium around with me, I’m mud from my feet to my head…” Rabjohn’s sketches illustrate men clambering in mud up to their knees trying to place “duck boards” for the soldiers to walk on so that they wouldn’t drown in the mud. The battle was also known for its deadly shelling, and R Rabjohn unsqueamishly notes and illustrates that , “[The Germans] shelled again, sixteen lay dead, the rest being taken away wounded. Ten dying later in hospital…One fellow cut in half, another head right off, back of head, legs off, arms of. Pieces of bodies lying here and there.” One might wonder how Rabjohn came through the carnage of the war without being wounded when so many of his friend were injured or killed. He did have his close calls, as he wrote 4 November 1917, “Frizs started to shell us again, keeping it up all night and us in a small dugout [with a tin] roof. One shrapnel ball came through just missing my head by half a foot., knocking dirt all over my face and the ball fell on my pillow…. Simmons and Watson were killed in their dugout, both being cut off at the hips…” The horrible battle ended near the end of November, and the Canadians returned to Vimy. Rabjohn was given the job of painting the crosses for his battalion’s dead, as well, he also sketched the crosses and sent a picture to the soldier’s relatives. In the spring of 1918, the Germans launched their offensive to the south of Vimy Ridge, but the Canadian sector was still active, and more of Rabjohn’s friends were killed. In the summer of 1918, the Allies launched their own offensive, known to history as “The Hundred Day Campaign.” The British and Dominion troops broke through the German lines and Rabjohn did illustrations of the German prisoners and wrote, “Still going hard, prisoners coming down by the hundreds…, The whole corps is moving up with the advance…. Heavy casualties coming down today and more prisoners.” Finally, on 11 November 1918, an armistice (ceasefire) was signed and the fighting ended. As Rabjohn wrote and illustrated, 11 November, “what a celebration! Thousands of civilians trying to do their best to do something for you—food, wine, beer. Arm in arm marching further into Mons. Still wondering, Can it really be true?” After months of long delay in Belgium and England, Rabjohn and his army comrades returned to Canada to rebuild their lives. In his final entry, 17 March 1919, he wrote, “…warmly welcomed by relatives. Discharged at midnight. Free men.” Wilson includes a barely adequate First World War Timeline listing dates and events, a short index and miserly suggestions for further reading. Overall, A Soldier’s Sketchbook is a remarkably singular addition to the extensive body of literature devoted to Canadians in “The Great War.” The story preserved in Russell Rabjohn’s diary, through his illustrations and presented by John Wilson, will provide readers with a deeper understanding of and feeling for the Canadian soldiers of “The Great War” than they will find in most other resources. Highly Recommended. Ian Stewart has marvelled at the Canadian National Memorial at Vimy Ridge and the Newfoundland Memorial at Beaumont Hamel and walked through the Canadian battlefields and cemeteries in Belgium and France. He spends his time researching Manitoba and the “The Great War” at the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum and Archives.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review | Table of Contents For This Issue -February 24, 2017 |