| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 9. . . .October 30, 2015

excerpt:

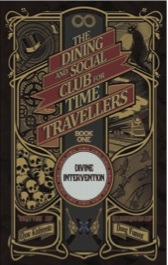

Thus author, Elyse Kishimoto, sets the stage for Louisa Sparks to travel the path that takes her to an unexpected end, and a beginning, too. The series title, “The Dining and Social Club for Time Travellers, Book One” that accompanies Kishimoto’s first self-published novel, Divine Intervention., clearly states that the end of this book is not the end. There are more adventures ahead. Louisa is an English child who loses both her parents in a car accident. Two weeks later, she’s picked up by her Grandpa George who takes her to live with him in a small French village. Four months later, it’s time for Louisa to return to school. The decision of whether she’ll go to school in the village, or in Paris, is up to her. She has two days to decide. School has never been her favourite place. She thinks school in the village will be safer, and she tells her grandfather she’s decided to stay. The next day Grandpa is chopping wood and finds a locket in a tree. How it got there is a mystery, but it turns out to have belonged to Louisa’s mother. Louisa thinks it’s a sign—her mother’s telling her that choosing ‘safe’ is not always the best thing to do. So, Louisa changes her mind. Before she leaves for Paris, her grandfather gives her more things from the past, among them the small pea coat he was wearing on a fateful day in 1940, when he lost his own mother. Soon after Louisa boards the train for Paris, she finds a strange item tucked into the deep pocket of her grandpa’s old coat. The item feels alive and looks something like a pocket watch, but it’s not a watch. It has all sorts of dials, and the hands move both clockwise and counter-clockwise. In 1940, when he was a small boy, Grandpa George had found it during an air raid on London. He’d been huddled against his mother in a subterranean train station for three days. His father was somewhere above, fighting fires. When his mother was asleep, George got up to chase a butterfly from that tunnel to another. A blast shook the earth, and the roof of the tunnel where his mother was collapsed. George raced back and tried frantically to claw through the rubble to get to her. He couldn’t. Almost blind with tears, he’d stumbled upon the strange time-piece in the debris. Then he’d witnessed an extraordinary thing. In the tunnel to which he’d chased the butterfly, a man lay slumped in a pool of blood on the station floor. George thought at first he was his father, but, upon going closer to try and revive him, George saw he was a white-haired man who just looked like his father. Another man suddenly appeared, aimed a gun at George and demanded George give him what he’d found. He called it a parallax. The white-haired man called this man Belthazzar. Belthazzar spewed vicious threats and said he was going to enjoy killing the white-haired man twice within the same hour. Instead, the white-haired man shot him, swore George to secrecy about what he’d seen, and died. George escaped up the station stairs, into the chaos of London streets, where he passed out. Here, the author fast forwards six decades, when George is living in France and Louisa enters his life. Louisa presses one of the buttons of the curious time-piece. There’s a click, the hands whirl. She lets go of the button and is transported to…a very strange place where she sees a man called Adalbert Uhrmacher, who, like her, is riding in a bubble through time. A short time later, in a manner she can’t explain, she returns to the train. She’s been gone only seconds, but her disappearance and reappearance have been noted by a street urchin named Gavroche. Though Louisa doesn’t know it yet, Adalbert Uhrmacher and Gavroche will soon figure prominently in her life. So will a long-lost, second cousin twice-removed known as Hignard Honeycut, a thief called Babet—who is Gavroche’s uncle—wraith-like creatures called Nephilim, and most ominously, Belthazaar, who has vowed to hunt down and kill all other time travellers, thus making himself the only person with the power to travel through time. The author seems to have borrowed liberally from well-known sources for both plot points and characters, (for example, Babet and Gavroche are ringers for Dickens’ Fagin and Dodger in Oliver Twist, with minor differences, and Louisa’s interactions with a boy named Troy are highly reminiscent of those between Anna and Olaf in Frozen). The concepts of time travel, parallel universes, and a villain whose entire reason for being is to take control of the world are certainly not new either, but the way Louisa experiences them is. Louisa is a character with considerable appeal, and the story, itself, is imaginative and intriguing. Unfortunately, there is also a lot of disconnect. The difference in how the book’s title and the same word is spelled in the text (travellers; travelers) is an early indication this book could have used some good editing. There are numerous characters introduced who have no real reason for being and serve to muddle up the actual story. Fontenbleau, Cabécou, Gruyère, and Haydee are a few. The author’s attempt to differentiate these, and other secondary characters, with unrealistic accents is also confusing. However, of more concern to this reader is the difficulty I had in determining how old the main character is supposed to be and in following her development. In the beginning, the reader is told Louisa could “barely manage a few words under normal circumstances” and “hardly spoke to her grandfather at first.” She was “convinced that going to school in Paris, or anywhere else for that matter, would be just the same as it had been in London: torture. Louisa was bookish and frightfully shy, so no one ever paid attention to her. And if they did, Louisa could never quite find the right words to say. She was like a ghost who haunted the hallways. Even those she considered her friends, seemed to look right through her.” Yet, very soon the reader sees she not only can manage to speak up, but that she does so with self-confidence in any circumstance. The first instance is when her cousin Hignard, whom she’s decided to call Uncle Hignard, picks her up in Paris. On the way home from the station, traffic is heavy. Hignard shouts insults at everyone, and instructs his butler/chauffeur, Planchet, to drive on the sidewalk where they nearly run down a delivery man. The delivery man yells at Hignard, whereupon Hignard waves his hat at him and says, “Good day to you, sir!” Louisa chides him. “Why Uncle Hignard, you get in a whole heap of trouble doing a rotten thing like that.” A short time later, she chides him again, this time for the way he treats Planchet. Throughout the book, her speech is insightful and grown up. Several times Louisa is described as tiny. The coat her grandfather gives her fit him when he was a small boy; she’s a full head shorter than a wolf hound. The nicknames ‘Red’ and ‘Carrot Top’ make her bridle with fury (just like they did a red-headed orphan named Anne Shirley). These things indicate she’s very young. Yet, when her parents go out for an evening anniversary celebration, she’s left alone; she visits her dying mother in hospital by herself; she fends for herself for a full month after arriving at her grandfather’s house, and decides where she will go to school; and she rides the train to Paris by herself. Louisa’s age is never given. People are complex and don’t always ‘act their age’, but I think the discrepancies between the descriptions of Louisa, her speech, and her actions throughout the book may make it difficult for young readers to connect with her. Another troubling discrepancy is between how careful Kishimoto is to not use foul language— she employs humour to keep things light when it comes to slurs: “‘Zat foghorn, zat lobster-back, zas rosbir!’ Madame de Winter spewed” — and graphic descriptions of torture, both threatened, and used, by Belthazaar. Except for Louisa, Gavroche, and Grandpa George, all of the characters are stereotypical comic-strip types. In comic books for young readers, we see battles of epic proportions, but we don’t see torture. Doug Feaver’s line-drawings are also done in varying styles. Some are realistic: Louisa, the dogs, Gavroche, and the animals described in chapter 17; most of the rest are the kind of caricatures better appreciated by adults than children. To be effective, illustrations need to do more than just reflect the text; they need to add a dimension to it. This is best accomplished on pages 203 and 212 where the gray/black/white silhouettes help create an ominous mood. In some places, the placement of images interrupts the flow, such as the ‘flying scene’ on page 33. That said, the drawings are skilful, and some do add interest. Recommended.

Jocelyn Reekie is a writer, painter and editor in Campbell River, BC.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

(Table of Contents for This Issue - October 30, 2015.)

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |