| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 9. . . .October 30, 2015

excerpt:

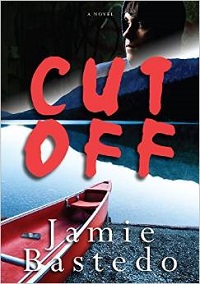

Cut Off is an ambitious novel that covers a lot of ground in its three hundred plus pages. The novel opens in Guatemala where readers are introduced to Indio McCracken and his family. His father is the CEO of a Canadian mining operation in the country while his mother is a Guatemalan. Indio is a guitar prodigy through whom his father tries to live vicariously and make up for his failed musical ambitions. Indio becomes a bit of an internet sensation after his father posts a video of him playing “Flight of the Bumble Bee” in triple time on his classical guitar. Indio has been mostly home-schooled, but he starts attending a local private school and is introduced to the World Wide Web, something that he was not allowed to access while at home. There is a great deal of tension in the McCracken household over how much Indio should be practicing. At one point, his father changes the locks on Indio’s practice room so that it locks from the outside and is only released through a timer. Needless to say, Indio chafes under his father’s expectations. After a protest regarding the mine and its treatment of locals ends with a protester shot dead by one of the family’s bodyguards, the McCrackens are whisked off to Calgary. Here, Indio attends a public high school for the first time, and, as his father stresses about the crisis facing his mine and deals with the lawsuits and other fallout, Indio is left largely to his own devices. To punish his father, he has given up music, and so his time is mostly spent losing himself online. He maintains two blogs one as Indio, musical prodigy, and the other as Ian, average rebellious high school student. Quickly, however, his time online becomes an obsession with serious consequences for Indio, and, at one point, it leads to a car accident that almost kills him. Feeling they have no choice, his parents send him to an addictions recovery program in Canada’s North where he is required to regain some balance in his life through outdoor activities, including a 50 day canoe trip. The writing in the book is accomplished, and Bastedo does a good job bringing the reader along on Indio’s long, troubled journey. Good teen fiction can be a tricky balancing act, needing, on the one hand, to be accessible to its audience, but, on the other hand, also wanting to present complex ideas that challenge its readers. Bastedo largely finds that balance: straightforward without being overly simplistic. Cut Out does not shy away from taking on challenging topics. The exploitation of indigenous communities by multinational resource companies, emotionally abusive parents, concussions and recovery from head injuries and internet addiction and the tough love that’s often necessary to deal with it are all complicated subjects that do not lend themselves to easy answers. Bastedo clearly expects his teenage readers to work a bit when it comes to making sense of the ideas raised in the novel, a refreshing starting point in a genre that often simplifies complicated subject matter to ensure the broadest possible audience. Even Bastedo’s references and allusions assume a willingness on the part of readers to engage with material outside of their everyday experience. Among the novel’s many epigraphs, for instance, he includes Oscar Wilde and Rudyard Kipling alongside more contemporary writers like Kevin Roberts, and Indio thinks very much in a classical music vernacular rather than a pop music one (though the Beatles do make a couple of appearance, but more on that later). The sheer volume of topics Bastedo covers, however, can sometimes feel overwhelming and, in the end, a little superficial. The book is divided roughly into three sections, and any one of them would have had ample material for an entire novel. Bastedo, for instance, provides a really good primer to the issues facing local populations when mines, who don’t care much about their well being, exploit the minerals in their mountains. At the same time in this section, the author sets up a really interesting dynamic between Indio and his father and the potential abuse at the centre of musical potential. Neither, however, feels fully developed by the time readers are abruptly moved to Calgary for the second part of the novel. There are reasons Bastedo wants to include all these threads Indio’s hyphenated identity as a Guatemalan Canadian who has never really experienced Canada and the paternal abuse both help explain his feeling disconnected in Calgary which, in turn, help readers to understand why he retreats into the internet but three hundred pages are not enough to explore these topics in sufficient depth. In the middle section being bullied, dating, the death of his dog, his car accident and recovery and his internet addiction come at the reader at such furious rate there is little time to really consider them in any meaningful way. Likewise, in the third section, there are a number of new characters introduced fellow teenage addicts but there are not enough pages to develop them beyond stock characters. The largest problem, though, is that issue that is central to the novel internet addiction while topical, is tricky to deal with in a novel aimed at teens. Our contemporary relationship with computers and the internet is in a constant state of flux that makes it hard to write about without seeming out of date. Indio’s addiction, for example, is rooted in his blogs. This felt a little 2010, which may not seem that far away, but, for the novel’s target audience, it’s almost an eternity. Something related to social media might have felt more up to date (Instagram and Twitter, for instance, strike me as areas where teens struggle with boundaries, more so than blogs) but even as I write that, I know it’s changing, and in a year it will be something new. Given the timelines involved in publish novels, capturing the latest zeitgeist is difficult. But it’s important because trying to be au courant but actually being behind the times allows teens to dismiss the book and not buy in. The pop music references also feel as though they’re meant for an older audience. While there are teens who listen to the Beatles (Indio’s pop music go-to when he wants to impress friends on his guitar) and Pink Floyd, for the average 15 year old that music belongs to their grandparents. Even some of the newer bands that get lip service, like Nirvana, U2 and Coldplay, are still old by the standards of a teen in 2015. Most of the book feels incredibly well researched (there is a Q&A with the author at the end of the book where Bastedo talks about his first-hand experiences as well as his conversations with people who have first-hand experience with the topics), but the musical references feel like a playlist of the music that Bastedo, himself, relates to most. Finally, I struggled with the sheer number and extreme nature of Indio’s experiences: his father’s directly responsible for a mining operation that exploits the local population, a protest against the mine turns deadly (and Indio witnesses the violence first hand), his dog is run over in traffic, Indio rolls his father’s BMW and spends months recovering from head trauma, he is addicted (rather than just obsessed with) to his blogs and people’s responses, he needs to be kidnapped and blindfolded to be taken to a remote camp to recover, etc. Any one of these would have been believable, but all together it feels a bit like overkill. In the end, though, these jolts of extreme situations might be the price of doing business in YA fiction as it attempts to lure readers weaned on Harry Potter and “The Hunger Games”. Even with these reservations, Cut Off is an engaging read with ambitious goals that will introduce YA readers to a range of topics that they might not be exposed to in their everyday lives. This book uses relatable situations to get teen readers thinking about various complex ideas exploitation, addiction, abuse, recovery, to name a few and to consider the consequences of actions that they may not have been forced to think about before. Recommended.

Scott Gordon is a high school librarian and English teacher in Ottawa, ON.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

(Table of Contents for This Issue - October 30, 2015.)

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |