| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 7. . . .October 16, 2015

excerpt:

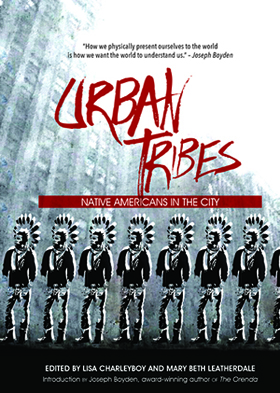

The title of this book - Urban Tribes – may seem like an oxymoron. Although 56% of the Aboriginal population in both Canada and the United States are urban Natives, living off reserve, (p. 130), it's fairly safe to assume that most non Natives hold to the “deeply held notion that in order to be authentically Indigenous, one must live on a reservation, or one’s traditional territory, and have a deep connection one’s land.” (p. 12) This book challenges that assumption through a collection of interviews, poetry, quotations, stories and reflections offered by a diverse collection of urban Native youth and young adults, living in large urban centres in both Canada and the United States. Lisa Charleyboy is known to CBC Radio listeners as the host of New Fire, a recently-launched show providing Aboriginal youth with a forum for conversation about contemporary social, political and cultural issues. She is deeply connected to her own Tsilqot’in culture, despite living in downtown Vancouver. Mary Beth Leatherdale, an award-winning writer and editor, admits that her knowledge of the urban Native experience “was based almost entirely on tragic news reports and the underlying stereotypes and prejudices they often inadvertently fuel.” (p. 13) Her desire to be an agent of change for those perspectives lead to her work with Charleyboy, and the result is Urban Tribes: Native Americans in the City.

Urban Aboriginals are no strangers to racism and prejudice, but many are choosing pro-active roles to overcome it. The chapter entitled “Shattering Stereotypes” profiles a number of individuals who have chosen to challenge discrimination through writing, song, and art. One of the most compelling examples is K. C. Adams’ paired photo series, “Perception”. In the first of two photos, the top of the photo is captioned with a label or slur: Hooker, Drug Dealer, and so on. At the bottom of the photo is a caption inviting the viewer to “Look again . . .” and in the second photo, the model’s identity, and accomplishments are profiled, making clear that the initial impressions are false, based on negative sterotypes. K. C. Adams states: “There are so many Indigenous people in Winnipeg who are leaders in their community and living normal or average lives. However, their stories never make it into the newspapers or on social media.” (p. 49) “Building Bridges” profiles a number of young people pursuing academic, professional and political goals. Some, like Maggie and Michaela live in Saskatoon, although their home reserve is Beauval, SK. They agree that “the schools are really good in the city”, and they “hang out with both Native and non-Native kids” but miss aspects of rez life. Still, they stay connected with their culture through a strong spiritual life, “praying a lot, spending a lot of time as a family, and going to an Indigenous church.” (pp. 80-81) Stephanie Wilsey, a Chippewa (Objibwe) student, originally from Ontario, is currently a full-time student at McGill. She is keenly aware of the historical reality of assimilation and the losses sustained by the rejection of native language, culture, and traditions. Still, she believes strongly that “being Aboriginal is so much more than being a victim”. Comfortable with her “modern Indigenous identity” (p. 87), she sees herself as a member of the vanguard of a new generation. Adrienne Keene, a Harvard PhD and currently, a post-doctoral fellow at Brown University, is acutely aware of the enormous pressures faced by Native American students; the focus of her work is on college access for Native American students who currently make up only 1 percent of college enrollment in the United States. For them, college education can be costly, not only financially, but also from an emotional perspective; her letter to a nameless “Native College Student” reflects the alienation and loneliness experienced when “there are very few people on campus who understand you, understand where you come from, and the pressures you face.” (p. 91) Keene also understands the pressure that Native students face to “give back” not only to their own communities but to the non-Native community, as well, and that continues to inspire her own work. Many others manage to defy all the negative statistics. Gabrielle Scrimshaw, raised by a single father in northern Canada, won a scholarship to U of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, and studied commerce and marketing, graduating in the top 5 percent of her class. She took a risk by moving to Toronto to work in RBC’s Graduate Leadership Program; far from family and her community, she began feeling a bit overwhelmed. Searching for a way to connect with other Aboriginals, she co-founded the Aboriginal Professional Network of Canada, providing a support network, a sense of community, and continuing professional education. She was able to succeed because of community support, and, now, she is committed to providing that support to others. The final chapter of Urban Tribes is called “Native Renaissance” and profiles the many forms of Native activism. #DearNativeYouth uses Twitter to provide messages of pride and inspiration to Native youth throughout Turtle Island (North America). Los Angeles was once infamous for an area known as “Indian Alley”, a stretch of back lane in a crime-ridden neighbourhood once largely populated by Native Americans who had moved to the city as part of the American government’s Urban Relocation Program. Indian Alley is now an urban gallery decorated by murals proclaiming Native culture. Musicians and actors proudly tell their stories of working hard to create careers that are richly informed by their roots, yet reach out beyond to the challenges of connection with the non-Native community. They are “Edgewalkers . . . a new generation of Aboriginal leaders who have no patience for the status quo, who are deeply interested in the potential of the future, and who have a hunger to contribute to a better world.” (p. 128) Their contributions will make a better world for everyone. Urban Tribes is an inspiring and thought-provoking work, whether the reader is Aboriginal or not. Although the book is only 136 pages long, it highlights the incredible diversity of young urban Aboriginals who are shaping a new cultural reality, built on the traditions of past generations. The book defies easy categorization: it offers social commentary, personal biography, vibrant graphic art and photography, and insight into cultural identity. Definitely worth acquiring for high school libraries and an excellent resource for Aboriginal/Native Studies courses.Highly Recommended. Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- October 16, 2015. |

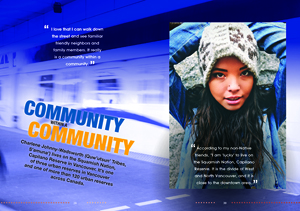

The “Tribal Citizens” profiled in the first chapter live in major urban centres but maintain their cultural connection in a variety of ways. Tyson Atleo, who will be next Hereditary Chief of the Ahousaht First Nation in British Columbia, was born, raised, and schooled in various urban centres, but he travels back frequently to the Ahousaht reserve from which he draws his sense of cultural identity and education. Others retain their connection through food: “No matter what urban city that I’m in, I have traditional foods in my house,” says Chantal Rondeau. “Traditional food such as moose and caribou meat, salmon from Yukon and Alaska, and frozen berries maintain a connection with “inner spirituality . . . because it feels like my land; these animals come from my land.” (p. 24) Ceremony – the practice of traditional spirituality, through smudge, tobacco, drums and chant – maintain Tasha Spillett’s sense of belonging to the Cree nation, while living in Winnipeg, “the largest unofficial urban rez in Canada.” (p. 29) And those who live in the Capilano Reserve, one of three urban reserves in Vancouver, enjoy “community within a community”.

The “Tribal Citizens” profiled in the first chapter live in major urban centres but maintain their cultural connection in a variety of ways. Tyson Atleo, who will be next Hereditary Chief of the Ahousaht First Nation in British Columbia, was born, raised, and schooled in various urban centres, but he travels back frequently to the Ahousaht reserve from which he draws his sense of cultural identity and education. Others retain their connection through food: “No matter what urban city that I’m in, I have traditional foods in my house,” says Chantal Rondeau. “Traditional food such as moose and caribou meat, salmon from Yukon and Alaska, and frozen berries maintain a connection with “inner spirituality . . . because it feels like my land; these animals come from my land.” (p. 24) Ceremony – the practice of traditional spirituality, through smudge, tobacco, drums and chant – maintain Tasha Spillett’s sense of belonging to the Cree nation, while living in Winnipeg, “the largest unofficial urban rez in Canada.” (p. 29) And those who live in the Capilano Reserve, one of three urban reserves in Vancouver, enjoy “community within a community”.