| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 7. . . .October 16, 2015

excerpt:

Red Stone is a dramatic and disturbing novel about a family caught up in tumultuous changes in the Soviet Union. Katya Halter, 11, lives in a village in Ukraine, then part of Soviet Russia. The family includes two sisters and two brothers younger than Katya, her mother and her father, who owns his own farm. Gerda, the housekeeper and Natasha, a young milkmaid, are also part of the household; later in the story, readers learn that the family "took them in". Katya's father is a "kulak", defined by Goldstone as follows:

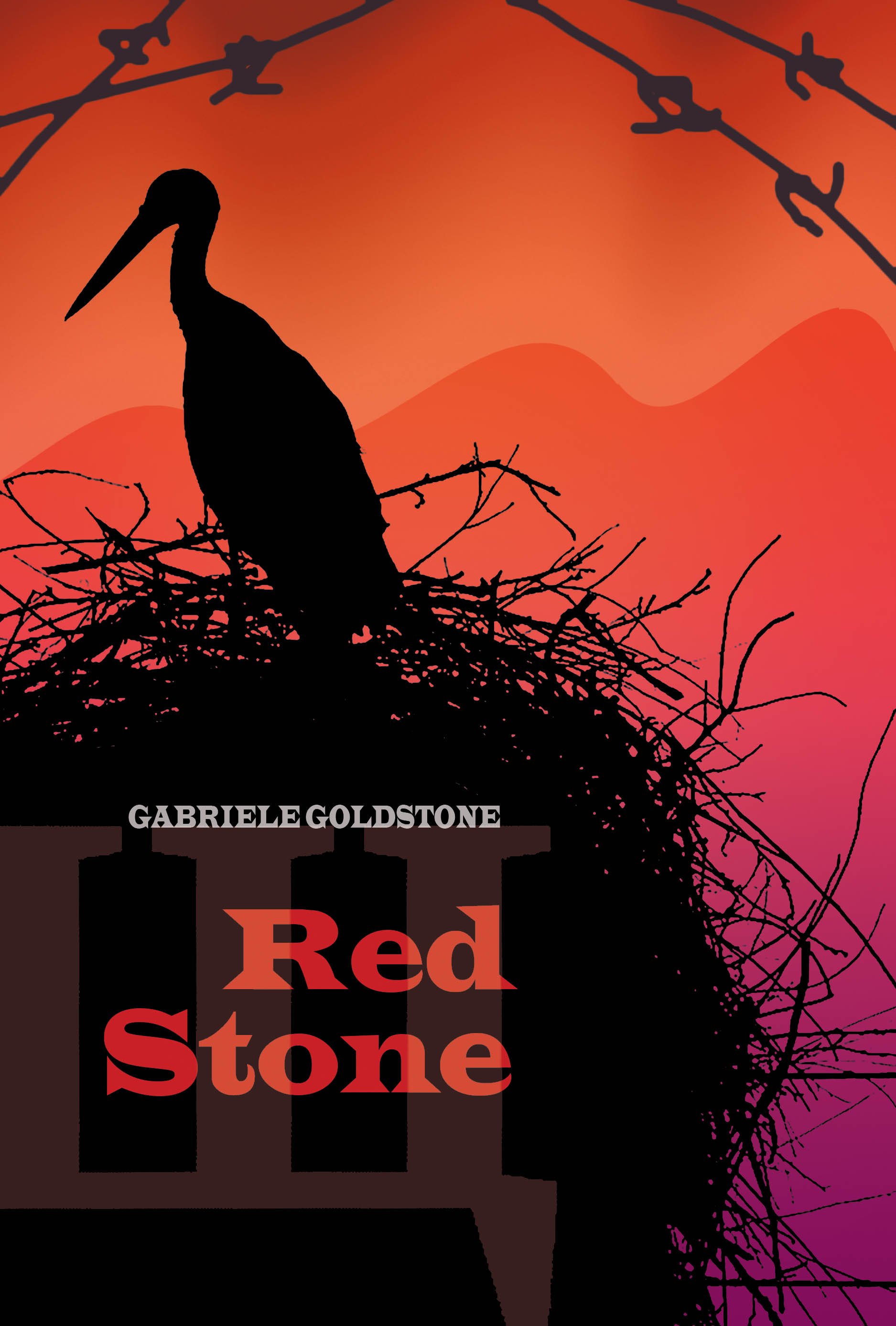

It would have been helpful if the author had presented some background information about Russian agriculture and land use in an “Historical Note” or “Afterword”. Until Czar Alexander II freed the serfs in the early 1860s, Russian agriculture was feudal in organization. In 1906, reforms under Czar Nicholas II allowed peasants to acquire plots of land from the aristocratic landlords through a payment system based on farm work. With the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the new government passed a Land Decree which took large estates from aristocrats with a view to forming collective farms. In the summer of 1918, the new government sent the army to the countryside to seize grain to feed itself and people in the cities, resulting in a widespread peasant revolt. Until July 1929, official policy was that kulaks be convinced to join the collective farms. Then, on January 30, 1930, Stalin, who had by then consolidated his power as dictator, decreed an end to the kulak class. Early in the novel, through a conversation between Aunt Helena and Mama, the author lets readers know that the Halters are "Russian Germans" or "German Russians". Readers learn that their maternal grandmother was born in East Prussia. Later, the milkmaid, Natasha, calls Katya and her sister "the goody goody German girls". More information about "German Russians" would have been useful, possibly to explain their status as "kulaks". Perhaps this information will be relevant if a sequel is planned that takes readers into World War II. Goldstone's novel opens in the spring of 1929 when Aunt Helena, Mother's sister, and her husband, Uncle Leo, "a brash man full of Bolshevik ideas", come for a visit from the larger town of Zhitomir. They arrive in an automobile, a novelty, bearing a doll as a belated birthday present for Katya, but when talk turns to the collectivisation of agriculture, Papa orders the visitors out of his house. Shortly after that, Katya eavesdrops on a secret meeting of local farmers discussing the end to private land ownership. One plans to emigrate; the others are undecided as to what to do. "I'll not let Stalin cuckoo his way into my life,” declares Papa.” Throughout the novel, the stork symbolizes independent farmers like Katya's father, while the cuckoo represents government forces which take over the farmers' land. Earlier, Uncle Leo complains about the noisy storks on the Halter family's roof. When Katya says they're good luck and bring babies, Uncle Leo says to Helena, "We don't need tradition or babies, do we, my dear Helena?" Later, Katya explains to her sister that cuckoos are lazy and lay their eggs in other birds' nests. The windmill is also important, symbolically - "tall like a strong tree, built on a mound of red granite boulders...While the field around it changes colour with the seasons, the windmills stays the same - arms reaching out to the wind, to the sky and, I like to think, to me," says Katya. Throughout her troubles, she keeps a little piece of red granite with her as a talisman, hence the title of the novel. The next major development is Papa's decision to slaughter his livestock to prevent the animals being seized for the collective farms. (The widespread slaughtering of animals by the kulaks led to cattle numbers in the U.S.S.R. declining by 50 per cent, which, in turn, led to a shortage of meat and milk, a loss not recovered until the 1950s. Grain production also fell, leading to the 1932-3 famine in the Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Caucasus regions.) Papa is taken away for questioning, and returns, beaten up. Later, police arrive with Uncle Leo to arrest him and take him away to prison as a "Class One Kulak." Shortly afterwards, Mama and the children are ordered to board a train to Siberia where they will work in a forestry camp. Gerda is separated from the family, arbitrarily charged with treason, and sentenced to hard labour in Archangel on the White Sea Canal Project. Natasha, who was frequently rebellious against the family, becomes a member of the organizing committee of the new collective farm. Two devastating deaths and much hunger and hardship in Siberia almost destroy the family, until an inspired idea of Katya's results in help coming from an unexpected source. Uncle Leo's villainy is made clear at the beginning. Not only is he anti-tradition and anti-baby, his very cigar smoke is oppressive; it "fills the room like a dirty cloud", and he flicks his ashes onto the floor. His negative depiction at the beginning contributes to the surprise ending, for he - Spoiler Alert! - is the children's rescuer.

Red Stone was originally published in 2009 as The Kulak's Daughter but has since been revised, expanded, renamed and republished in its current form. Inspired by, and dedicated to the memory of "Else", the author's mother, Red Stone is a gripping tale. Recommended. Ruth Latta is an author living in Ottawa, ON. For more information about Ruth’s novels, visit her website at http://ruthlattabooks.blogspot.com

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- October 16, 2015. |