| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 15. . . .December 11, 2015

excerpt:

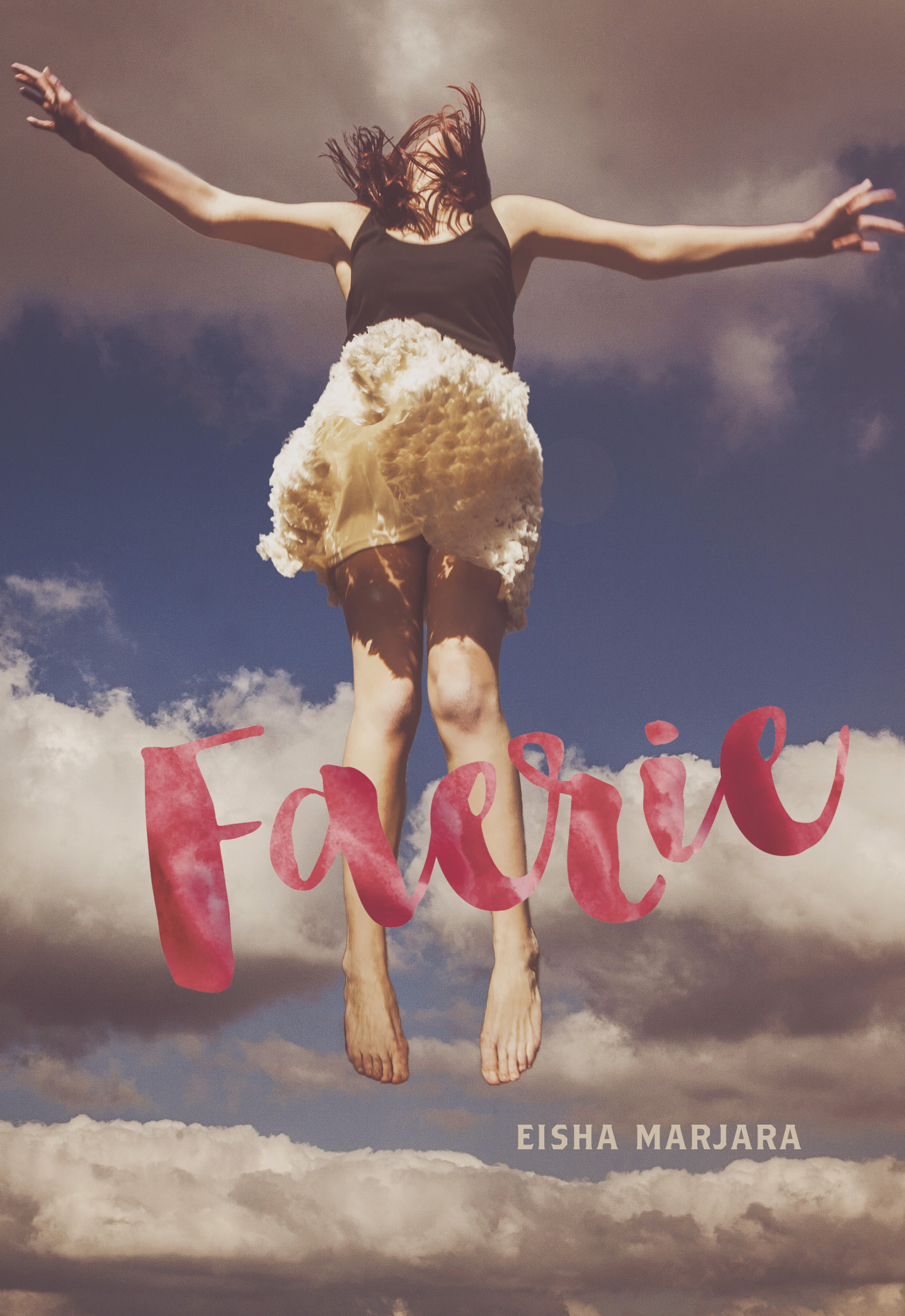

Faerie plunges the reader into 18-year-old Lila’s life on one of her darkest days. She’s in a psychiatric ward, being treated – not very successfully – for anorexia nervosa. On this day, she decides to commit suicide by walking out into the frigid Montreal winter wearing nothing but her hospital gown. She weighs just 68 pounds. Lila survives and is placed into the Patient Acute Care Unit, which she sees as solitary confinement like in prison. Until she gains three pounds, she’s not allowed any form of entertainment or communication with the outside. She’s not allowed to get out of bed or speak to anyone but the staff. And she has to eat 3,000 calories each day. Lila views the hospital staff as enemies and her treatment as torture. For her, losing weight means that she is in control of her life, and she sees each pound forced on her as a loss of autonomy. Author Eisha Marjara uses these struggles as a backdrop for Lila’s inner thoughts as she considers how she got to this terrible place – physically and psychologically. Readers find that Lila’s parents are Punjabi immigrants and that her mother finds great happiness in making high calorie traditional dishes for her family. This diet has no effect on Lila’s younger sister who is naturally lean, but Lila inherited different genes, and by the time she reaches high school, she considers herself as obscenely obese. Readers can’t be certain what Lila actually looks like, but she sees herself a fat brown girl in a sea of tall lithe Catholic white girls. There is one scene in the novel when Lila is trying on prom dresses. She looks in the mirror and sees herself as a pink blimp, but when her mother opens the door to look in, she says, “Lila, you look so beautiful. Like a fairy tale princess!” Lila feels pressure to live up to her parents’ dreams, which are to excel in science or math and to become a professional, but she’s drawn to the arts, in particular photography and literature. At school, she’d like to fit in, but because of her ethnicity and what she perceives as her faulty appearance, she is always an outsider. Added to this is a desperate fear of growing up. She does not want to become a woman if it means becoming her mother, a fat Punjabi housewife whose only joy is in cooking. Lila feels that there’s a faerie deep inside her waiting to get out, but that it’s covered in layers of fat. She begins a diet in an attempt to reveal her true self, but it gets out of hand. Her original 140 pounds is whittled away to 78 and mid-sentence, while chatting with a cashier at the supermarket, Lila’s heart stops. That’s when she’s admitted to the hospital. The author does a good job of portraying anorexia as a serious psychiatric illness, and she convincingly puts readers inside Lila’s head without glamourizing the illness. This is a key point as many novels on anorexia end up being used as guide books on pro-ana blogs and websites. While Marjara does show in detail the various tricks Lila uses to hide her food and burn off calories, it’s done in a skilfully distasteful way. The parents are portrayed as regular loving folk, having their own struggles adjusting to a new country, sometimes making regrettable decisions because they’re human, but not out of malice. The nurses and doctors are described as the enemy when Lila’s illness is at its worst, but, as she begins to recover, her view of them evolves as well. The story comes full circle in an unexpected way. The ending is by no means pat, and there’s no guarantee that Lila will ever be cured, but readers will come away with a sense of hope. The writing is polished and poetic, and the editing is spot-on. A well-constructed and thoughtful novel on a difficult subject. I read Faerie in a single sitting and was thoroughly entranced. Young adult readers (and adults too) will appreciate it. Highly Recommended. Marsha Skrypuch is the author of many books. Her most recent, Dance of the Banished is the 2015 winner of the Geoffrey Bilson Award. Her first novel, The Hunger, was about an anorexic teen.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue - December 11, 2015

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |