| ________________

CM . . .

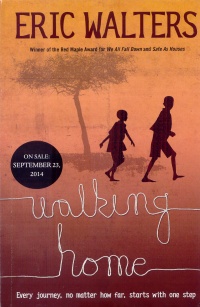

. Volume XXI Number 9 . . . . October 31, 2014

excerpt:

With his latest work of juvenile fiction, Eric Walters adds to the growing list of Canadian children’s books that offer glimpses into war-torn corners around the world. Walking Home is suitable for readers aged 9 through 13 and will appeal to those who enjoyed Deborah Ellis’s Breadwinner series, Sharon McKay’s Thunder over Kandahar, and Allan Stratton’s Chanda’s Wars. With many similarities to the above works, Walking Home is also familiar due to its predictable structure—that of the hero’s journey so common in fairy tales. Readers who might find the traumas endured by 13-year-old Muchoki and his little sister Jata overwhelming will be comforted by the structure’s implied certainty that everything will turn out all right. Indeed, the promise is implicit in the book’s title, Walking Home, so, of course, the children arrive safely in the loving arms of their extended maternal family. Further, on their long walk from a refugee camp to his mother’s childhood village, Muchoki encounters helpers and overcomes obstacles similar to those readers will remember from fairy tales—and the characters, themselves, are barely more developed than those from the average fairy tale. While the caring older brother succeeds in his quest due to the kindness of strangers rather than magic, Walking Home is no work of stark realism. Muchoki certainly does witness horrific violence when his village is ransacked in tribal warfare and his extended family murdered; indubitably, he and his sister experience displacement in a refugee camp and are ultimately orphaned. But even so, Walking Home is far less gritty than it might be. Walters’s decision to provide hearty doses of hope throughout the tale results in obfuscation of many depths at play in tribal warfare and civil unrest, not to mention the purgatory of the refugee camps, which the children easily escape. Therefore, readers familiar with actual political events in Kenya, as well as those expecting a more nuanced expose of the ways that postcolonial friction affects individuals in area of conflict, may take issue with how Walking Home reduces complex situations to a universal good versus evil binary. This deliberately oversimplified approach will certainly make the story more palatable for squeamish readers (not to mention adult gatekeepers), but what’s lost may come at too high a price. But Eric Walters has made a bold, unusual, and very welcome move with Walking Home; to help overcome the aforementioned gaps in the text. Walking Home’s “digital companion” website offers a plethora of interactive, multimedia resources that expose more of the realities at play in Kenya. Like many brilliant ideas, this concept is so ingenious that it seems simple: provide videos, photographs, factual information, maps, audio files of the author reading his work, bits of manuscript revisions, a bonus chapter, and more. The only question viewers might ask is—why doesn’t every book include such online treasures? These supplementary materials enable greater insight into the complex Kenyan political situation and provide an enriched understanding of the landscape and culture. However, while the concept is brilliant, the delivery is plagued by several shortcomings. Material is organized by chapter but otherwise decontextualized. Some resources don’t seem to fit clearly or logically with the chapter they supplement, despite the icons in the book’s margins. More seriously, though, the universalization marring the story not only remains present in the web content, it deepens. Videos of Canadians walking the characters’ journey, as well as the author’s insistence that his own (genuinely traumatic) childhood losses are in any way comparable to enduring ethnic violence and relocation to a refugee camp, indicate a deeper disconnect with the important cultural specificities that distinguish Kenya as a unique country with a very particular political history. While universalization achieves its purpose of demonstrating what a small world we live in and how similar we all are, such platitudes also disrespect and detract from the ways in which Kenyan culture, peoples, and history are different from all others. The website and its resources would be more successful if they acknowledged this with greater detail and emphasis. Nevertheless, Walters has created a wonderfully informative and usable digital companion to his novel. Canadian children’s literature will be much the richer if others follow in his footsteps and provide similar supplementation to their print materials. Without the website, Walking Home is a hopeful story about perseverance and the power of humanity’s essential goodness to overcome all obstacles. As such, the book makes a satisfying story—but not a truly useful teaching tool for examining the plight of Kenyan refugees. The book alongside its digital companion offers a more useful blend of hope and reality. Recommended with Reservations. Michelle Superle is an Assistant Professor at the University of the Fraser Valley, where she teaches children’s literature and creative writing courses. She has served twice as a judge for the TD Award for Canadian Children’s Literature and is the author of Black Dog, Dream Dog and Contemporary, English-language Indian Children’s Literature (Routledge, 2011).

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home | Next Review | Table of Contents for This Issue - October 31, 2014 | Back Issues | Search | CM Archive | Profiles Archive |