| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 39 . . . . June 12, 2015

excerpt:

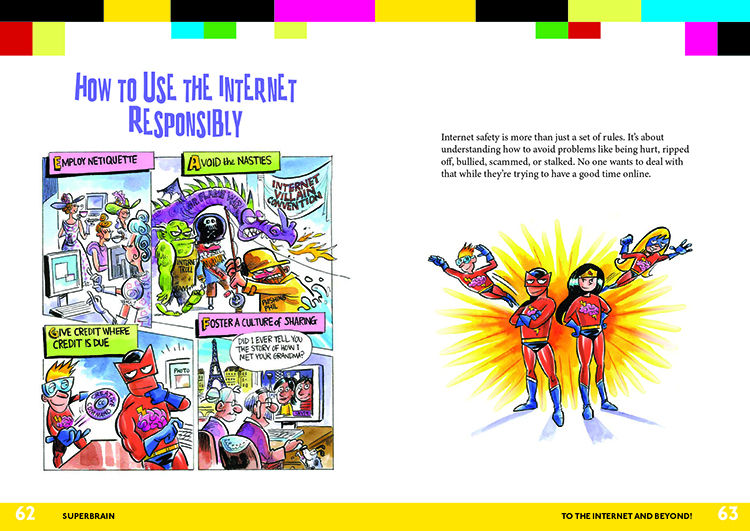

Superbrain: The Insider’s Guide to Getting Smart, written by staff from the Toronto Public Library, is, according to the publisher, intended for elementary and middle school readers. Its purpose is showing learners how to learn, and it hails lifelong learners as superheroes. This superhero theme continues throughout the book. There are four chapters, the first of which is titled “Prepare Your Lair” which would lead readers to think that it is going to be about preparing one’s workspace. Instead, it offers a simple quiz to determine whether the reader is an auditory, visual or kinesthetic learner and explains the differences among these learning styles. This chapter also encourages readers to take advantage of all that the public library has to offer and stresses the importance of research in everyday life and how it applies to certain professions and activities. For example, an actor might research a particular role while a teen who wants to fix his bike might view an online tutorial on bicycle repair. Chapter Three, “Tackle Your Villains”, helps learners to discern between facts and bias. In this chapter, there is a list of tools, common to both print and online sources, that can assist readers in finding the information they need: a table of contents, headings, indexes, glossaries, pictures and charts, tables and graphs, as well as a listing of general categories in the Dewey Decimal system. Other tips in this chapter include making notes on recipe cards or sticky notes (or creating bookmarks online), the difference between primary and secondary sources, and evaluating sources for accuracy by examining the writer’s credentials, the web site URL, publication date and the writer’s purpose. A quiz invites readers to find out whether they are critical thinkers. One flaw in this chapter is that it really doesn’t explain how to take notes nor does it mention paraphrasing or plagiarism; it simply states, “Include one idea or quote per note card. Keep it short and sweet.” Finally, the fourth chapter, “To the Internet and Beyond”, provides information on plagiarism, netiquette, internet hoaxes and scams, copyright, creative commons license, phishing, cyber-bullying and the dangers of downloading pirated software. The web addresses for three internet safety sites for kids are also included. Of all the chapters, this one is, perhaps, the most useful and relevant. Throughout the book are profiles of some “super-learners” whose accidental discoveries became world famous, one example being the invention of penicillin by Alexander Fleming. These profiles, though interesting, are rather superfluous. Though the book has good intentions, it is inconsistent in its practicality and usefulness, creating an imbalance among the chapters. Some critical information is missing. One example is that the author(s) talk about organizing notes, but they never state what to do with those notes afterward. Should the student use the notes to write an essay, a skit, a jingle or to create a slide show, a play or a diorama? “Share your findings” is one of the four basic steps in research mentioned in the second chapter and a critical component of information literacy; yet examples of the various ways to share one’s findings are not given. Another example is that the author does not explain that, depending on the research question, some resources will be better than others. The illustrations, done in comic book style, suit the superhero theme of the book, but they might be a bit too juvenile for the upper end of the publisher’s intended audience. Two appendices are provided, the first explaining Melville Dewey’s thought processes which helped him to shape the Dewey Decimal system, and the second is a “Cyber Glossary” offering Internet terms. Generally, Superbrain: The Insider’s Guide to Getting Smart has value, but it is missing some important information and requires some revision in order for the content to assist a student from an assignment’s beginning to its end. Recommended with Reservations. Gail Hamilton is a former teacher-librarian in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home | Next Review | Table of Contents for This Issue - June 12, 2015 | Back Issues | Search | CM Archive | Profiles Archive |

The second chapter, “Know Your Mission”, gives readers the four basic steps in research: gather information, organize facts, evaluate your findings, and then present them. Here the reader is introduced to the K-W-L chart (often taught in schools, at least it is here in Manitoba), three columns in which learners write what they Know, what they Want to know, and what they have Learned. (It would have been beneficial to have shown an example of a KWL chart already filled in.) Tips for time management include having a place to record notes, creating a workspace, eating nutritious foods, getting enough sleep, and building in short breaks so that ideas can percolate. (How proper nutrition and getting enough sleep relate to time management is rather questionable, but it is obvious that feeding the body properly and being well-rested contribute to optimum health, translating into one’s being better prepared to tackle life’s challenges.) The final bit of information in this chapter is a quiz which will show readers what kind of leadership style they possess: democratic, autocratic or consensus. This information is included because there will be times that kids will need to work on assignments or projects as a team. But the quiz appears out of nowhere, without preamble, and would have been best introduced by the paragraph that appears on the following page which describes the main differences among the three leadership styles.

The second chapter, “Know Your Mission”, gives readers the four basic steps in research: gather information, organize facts, evaluate your findings, and then present them. Here the reader is introduced to the K-W-L chart (often taught in schools, at least it is here in Manitoba), three columns in which learners write what they Know, what they Want to know, and what they have Learned. (It would have been beneficial to have shown an example of a KWL chart already filled in.) Tips for time management include having a place to record notes, creating a workspace, eating nutritious foods, getting enough sleep, and building in short breaks so that ideas can percolate. (How proper nutrition and getting enough sleep relate to time management is rather questionable, but it is obvious that feeding the body properly and being well-rested contribute to optimum health, translating into one’s being better prepared to tackle life’s challenges.) The final bit of information in this chapter is a quiz which will show readers what kind of leadership style they possess: democratic, autocratic or consensus. This information is included because there will be times that kids will need to work on assignments or projects as a team. But the quiz appears out of nowhere, without preamble, and would have been best introduced by the paragraph that appears on the following page which describes the main differences among the three leadership styles.