| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 34 . . . . May 8, 2015

excerpt:

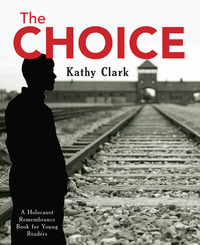

Kathy Clark's compelling novel was inspired by the experiences of her father, Frigyes Porscht, and is dedicated to his memory. Raised by "her mother and a loving stepfather", Clark got reacquainted with her father in 2000 and "learned the events described in this book" as she explains in an author's note at the book’s conclusion. Readers who don't know much about Hungary's World War II history will appreciate Clark's introduction explaining the factual background behind The Choice. During their occupation of Hungary (March 1944 to April 1945), the Nazis killed about 550,000 Hungarian Jews. Prior to the German invasion, Hungarian Jews were subjected to human rights infringements, and some were sent to forced labour camps, but, as a group, they had not yet been forced into ghettos or deported to concentration camps as other European Jews had. Hungary's Arrow Cross party, which was like the Nazi Party, was illegal and operated in secret until the invasion when it took over the government of Hungary and cooperated with the German elite force, the SS (Schutz Staffeln). Many Hungarian Jews were deported to Poland, to the network of concentration and death camps with forty satellite camps, which was known as Auschwitz. The novel opens in a Budapest classroom in October 1944, when the teacher, Brother Ferenc, speaks to the students about their fast-approaching confirmation in the Roman Catholic church. Hendrik Varga and his best friend, Ivan Biro, both 13, are impressed by the friar's statement that this rite of passage means that they are now adults in their religion, able to know right from wrong. Hendrik and Ivan have been busy running and building their muscles because Ivan wants them both to join the Arrow Cross, in which his father is a sergeant. Hendrik likes the exercise and company, but he is uncertain about joining and knows his mother does not want him to do so. He and his family have well-kept secret. Until 1939, when he was eight, Hendrik lived across the Danube River in Pest and was called Jakob Kohn. That year, after his Uncle Peter was taken to a forced labor camp, Jakob's parents, with Jakob and their maid, Magda, walked out of Pest and never came back. They crossed over to Buda where they changed to the family name "Varga" and practised Roman Catholicism (learning the customs from Magda, a Catholic). Jakob's father had secured false identity papers and found a new job. They no longer associated with their relatives in Pest. "I am responsible for our safety," his father told him. "I cannot save everyone I love." Hendrik's life again changes completely on October 1944. That day, Ivan accompanies his father on patrol. Left on his own, Hendrik decides that he must reconnect with his relatives in Pest, particularly his cousin Gabor, whom he remembers studying for his bar mitzvah, a boy's rite of passage to manhood as a Jew. Before his confirmation as a Catholic, he wants to talk about the religion he half-remembers. Bicycling across a bridge, passing through a checkpoint, he sees people wearing yellow stars on their clothing being rounded up. The ghetto wall, under construction, obstructs his return to his old neighbourhood, but he gets there by climbing an oak near the wall and dropping down on the other side. There he sees boarded-up houses and businesses and ragged distraught people on doorsteps. His Aunt Mimi and Cousin Lilly share quarters with three or four other families. When they talk, Mimi assures Hendrik that his father "made the right choice for you," but Hendrik is angry that his father abandoned family members, and he becomes convinced that he must know his Jewish heritage before considering confirmation as a Catholic. Vowing to return, he leaves, feeling highly agitated. Though the author uses a coincidence at this point, readers will be too caught up in the story to question it, and, in any case, coincidences do happen. On leaving the building, Hendrik runs into the Arrow Cross officer patrolling the neighbourhood - Sergeant Biro, Ivan's father. When the sergeant greets him as "Hendrik", he blurts, "I am not Hendrik...I am Jakob Kohn. And I am a Jew." With this admission, all hell breaks loose. Gabor appears and is shot down. Mimi, Lilly and Hendrik/Jakob are loaded onto a truck with other Jews, bound for the railway station, then a cattle car to Auschwitz. Sgt. Biro calls for Ivan, who appears, and orders him back to the neighbourhood in Buda to round up the "Vargas, or whatever their name is." In the overcrowded cattle car on the long journey to Auschwitz, Jakob blames himself, but he also rages against Ivan, vowing to make him pay for obeying his father's order to go and round up Jakob's parents. Authors who write about the Holocaust do so because they want future generations to know about it and learn lessons from it. Clark's choice of photographs as illustrations shows good judgment. (Her sources are Shutterstock, the United States Holocaust Memorial, Yad Vashem and the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, with two pictures from her family album.) These black and white photos include scenic shots of Budapest before and after the occupation, Arrow Cross soldiers, prisoners at railway stations, barracks and bunks at Auschwitz, and post-war rubble. She has not included photos of piled-up corpses or emaciated prisoners. Clearly Clark seeks to educate young readers but not give them nightmares, and so she selected photos that are sobering but not terrifying. Black and white photos create a stark, somber effect but also send the message that the story happened long ago before the advent of colour photography, not in the recent past. Similarly, Clark makes wise narrative choices in presenting life at Auschwitz. She chooses the third person, which distances the reader to some extent from the central character, rather than the first person, which requires the reader to identify with the protagonist and experience everything "up close and personal." The story involves violence, but, sadly, young people of today are inured to it, and certainly teenagers can cope with what Clark includes. Rather than spell out every gruesome detail, she leaves it to the reader to grasp, or not grasp, what is happening. For instance, when Jakob, in a line-up of prisoners approaching the "sorting table", sees the ill, young and elderly being separated into one stream and the strong adults into another, he quickly says he's 16 so he can join the able-bodied group. Readers are left to figure out what happens to the weaker group. In the camp there is an "unspoken understanding that friendships were not to be formed. Too many people died each day. They all suffered enough without the added anguish of losing someone they loved." Nevertheless, Jakob makes friends with Aron, a boy his own age with a strong survival instinct. Some weeks later, through a crack in the barracks wall, they see among the incoming prisoners an Orthodox Jewish youth a few years their senior. Though Aron predicts that he won't survive, the newcomer, Levi, arrives in their barracks. When Levi prays, Jakob asks the meaning of the words. Levi explains, and he adds that he can't let his current plight separate him from God. Aron, in contrast, says that, "God, if there is one, has clearly forgotten about us. Spare your energies for surviving." When Jakob asks Levi to teach him about Judaism, Levi is happy to do so. Until meeting him, Jakob has been sustained only by his hatred for Ivan, but, with Levi as a friend, he focuses more on spiritual matters, not revenge. Though Levi values his life, he dies taking a stand against an oppressive, brutal regime. I was surprised at my emotional reaction to this plot development, considering that I am a seasoned veteran reader, and I had also helped a Hungarian Holocaust survivor write her memoirs. The tears I shed over Levi's death show that Clark is a skilful writer. Jakob and Aron's escape, two thirds of the way through the novel, is a welcome change of pace, full of tension, suspense and action. Jakob's revenge plans against Ivan arise again, but with a surprising outcome. Indeed, the working-out of the novel includes more surprises, closing on a sober but inspiring note. The Choice is an excellent historical novel - for readers who are teenagers or older. The publishers are convinced that it is suitable for nine to thirteen year olds, but at the younger end of this age range, children lack the general knowledge to appreciate it. Teenagers, who have read more and possibly learned more history, will get more out of it. Highly Recommended. Ruth (Olson) Latta, a former elementary school teacher, has a Master's degree in History from Queen's University. For information about her books visit http://ruthlattabooks.blogspot.com

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home | Next Review | Table of Contents for This Issue - May 8, 2015 | Back Issues | Search | CM Archive | Profiles Archive |