| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 34 . . . . May 8, 2015

excerpt:

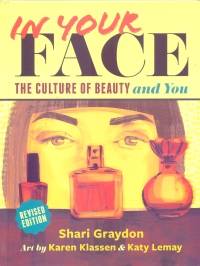

Ten years after its first release, Shari Graydon’s In Your Face has been given an anniversary makeover to attract a new set of readers. Gone is the thin 6¼” x 9” book that might have modeled itself after an art history guide, with its grayscale pages and reproductions of classic statues and paintings. In its place is a plumped-up volume of magazine-style layout and proportions (7¼” x 9½”), with colorful collage images. Updated for a contemporary readership, this revised edition extends an invitation to tweens or pre-teens used to image-rich Web and multimedia content. Dramatically different dimensions and design elements only enhance the substance and structure that already underlay In Your Face. First and foremost, the book’s central purpose remains unchanged: to educate readers about the political and economic forces governing standards of beauty. The author contemplates the myths and conventions that inform “the culture of beauty” which encompasses fashion, hairstyles, makeup, gender expression, and other aspects of personal appearance. She also demonstrates that the definition of beauty is elastic, depending upon time and place. Essentially, the book models critical thinking skills for readers who might otherwise unquestioningly buy into their culture’s beauty ideals. At its core, much of the content in this revised edition retains its basic shape, although it has been nipped and tucked and augmented to favorable effect. In terms of organization, for example, the table of contents, set out as a grid in 2004, here reverts to a traditional linear list. Ten chapters, the last two of the original 11 having merged, are fronted by an introduction renamed “Letter from the Author,” and followed by an afterword, “Tuum Est.” In addition, each chapter now begins with a page that frames its topic with a border and ends with a summary of take-away points, this time not in a bulleted list of “Image Reflections,” but rather in textboxes under the nattier title of “Double Take”. A few touch-ups to the back matter means it consists of “Notes,” “Acknowledgements”, “Image Credits” (in place of “Photo Credits”), a modified “Index”, and a new section, “About the Author and Illustrators”. The body of the text has been further contoured. For instance, excised are names of celebrities, movies, and brands no longer as trendy as they were a decade ago (e.g., Tiger Woods, Pretty Woman, and “Manolo Blahniks”). Also trimmed are redundancies, transitional phrases, rhetorical questions, hyperbole, extraneous details, and some of the more blatant descriptions of puberty, piercings, and cosmetic procedures. The text still relies on the second-person point of view, but the tone is more informal yet simultaneously more objective (that is, less personal) than before. Infographics contribute to the enhancement by reframing previously wordy comparisons as streamlined tables and diagrams, thereby reducing the density of information. To round out the content, updated research and references to selfies, social media, and video games replace older statistics and mentions of TV and newspapers. What really rejuvenates In Your Face, however, is the bold new magazine format. The splashy pages, with columns, sidebars (left, right, and bottom), blocks of text, “pull quotes,” and headings in a variety of font styles and sizes, inject vitality into the book. This new layout offers up information in smaller, discrete chunks. Meanwhile, the color scheme connotes a youthful vibe with a hint of maturity in its toned-down tertiary hues of maroon, coral, gold, and teal. These intense colors complement the collage-style artwork, a mash-up of found pictures and illustrations that are Pythonesquely playful; this art replaces most of the photographic reproductions of “high art” in the earlier edition. By and large, the restyling offers material that is more relevant and less hierarchically organized; consequently, it will attract a fresh set of readers, free to experience images and text in the order they choose, as if they were perusing an actual magazine. The book anticipates its new reader base will largely be younger, female, and more culturally diverse than it was ten years ago. Its size and cover composition (it uses an illustration instead of the 2004 photograph) suggest the new readers are on the younger end of the spectrum of young adulthood. Again, pointing to the cover, these readers will likely be female, because the illustration depicts a pair of eyes gazing at bottles of nail polish and fragrances, items typically associated with the feminine domain. Of course, males should read In Your Face and benefit from it, but the writing and images are slanted towards females. Finally, the text demonstrates a global awareness, rephrasing specific references to North America, Europe, and Ancient Greece, for example, in more generic ways. Therefore, even if libraries possess a 2004 copy of In Your Face: The Culture of Beauty and You, they should acquire the revised edition (available in hardcover, paperback, or e-book), because the made-over medium could reach more young adults with its important message. It would pair up nicely for thematic and display purposes with Flawed, an NFB animation by Andrea Dorfman that explores adolescence and body image. Already in 2004, In Your Face was attractive. Thanks to the treatment of a talented trio—author Graydon and illustrators Karen Klassen and Katy Lemay—it now possesses a revitalized visage. Highly Recommended. Julie Chychota makes her home in Ottawa, ON, and facilitates communication for post-secondary students with hearing disabilities by capturing speech as text on her laptop.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home | Next Review | Table of Contents for This Issue - May 8, 2015 | Back Issues | Search | CM Archive | Profiles Archive |