| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 32. . . .April 24, 2015

excerpt:

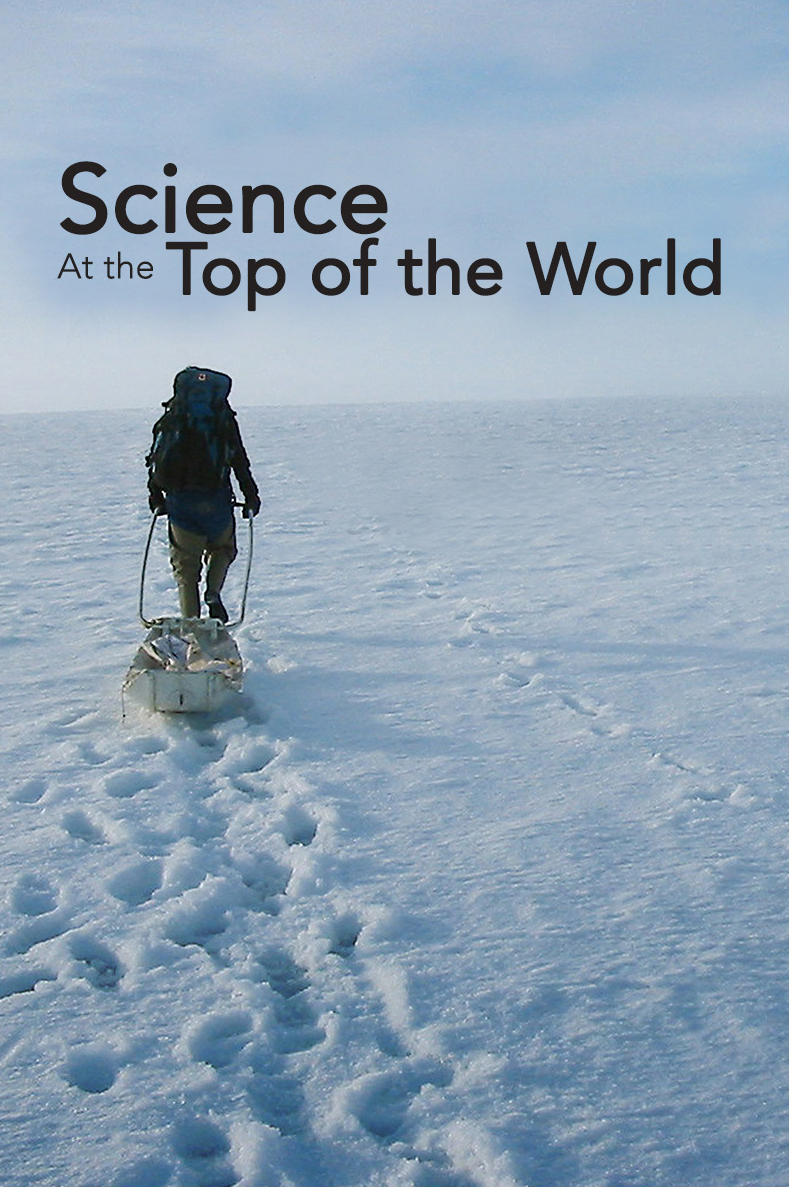

Each day there is more news of the impact of global warming on ecosystems and their inhabitants. This morning it was an item reported by National Geographic that “globally, one in eight – more than 1,300 species [of birds] – is threatened with extinction.” Two days ago, the BBC reported on an article published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society that concluded economic development is driving the extinction of minority, world languages. Like the extinction of a species and the repercussions this empty niche has on an ecosystem, the loss of a language is commonly tied to the loss of a culture in the global human community. In this context, the film, Scientists at the Top of the World could not be more timely. It is a film about the changes in Canadian arctic ecosystems that scientists are seeing, recording and beginning to understand. The film was directed by Partick McGowan. He and his crew travelled with scientists from the Geological Survey of Canada, The Canadian Centre for Remote Sensing, the Canadian Space Agency, and Laval University who are working for Parks Canada. Small teams of these scientists are studying on the ground in Ivvavik National Park in the northwest corner of the Yukon Territory, in Quittinivpaaq National Park at the top of Ellsmere Island in Nunavut and in Trongat Mountains National Park along the Labrador Sea in northern Labrador. These are three of the 12 parks in the Canadian arctic. Stephen Woodley, Chief Ecosystems Scientist for Parks Canada, tells viewers that more than 220,000 square kilometers in the Arctic are part of the national park system, and that Parks Canada is increasingly becoming an Arctic focused agency as a consequence of climate change (read the second excerpt above). Through narration and the voices of the scientists working in the Yukon and Labrador, viewers learn that they are there to study how the ecosystems in the park are responding to climate change in order to create useful models from which to predict, with confidence, what is going to happen to the parks as the Arctic warms. To do this, they collect samples of vegetation and construct ecotypes - “categories of vegetation” that enable patterns of plant diversity to be detected within each of the parks. They also gather photographic information, identify areas of permafrost and discontinuous permafrost, measure the depth of the permafrost and the depth to which plants can root, study water sheds, set up portable weather stations, and determine waypoints using handheld GPS devices. They then link this ground data to pixel information in satellite imagery of these regions. Given the location of Quittinirpaaq National Park at “the tip of North America”, the focus is on ice shelves, sea ice, the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems, and identifying and recording the diversity of microbial life that operates in arctic extremes. Warwick Vincent, an aquatic ecologist at Laval University, suggests that the first aim is to determine what’s actually there. Then, the next aim is to figure out what each organism is doing and how it manages to exist; that is, to determine an organism’s adaptive characteristics. And the final aim is to understand how each organism is most likely to respond to changes related to future warming. As in the previous two sites, much of this data is linked to satellite images of the park. Through several iterations of this type of field work, paired with satellite imaging technology, the scientists are able to monitor changes in all of the components for which data exists. The information collected extends beyond measurements and images to include the traditional knowledge of the original human inhabitants of Canada’s arctic regions, the Inuit. As one of the scientists explains, the scientific data from the North is limited; it doesn’t go far into the past. The Inuit, however, have memories of the past through experiences and oral stories, and these memories provide information about periods of good hunting and fishing, when to expect the formation of ice and breakup, and times when it was early or late, and most recently, when no ice formed at all. They also are aware of the presence of birds, and other forms of animal and plant life, never before observed in the Arctic. This knowledge, in combination with the knowledge possessed by the individual scientists and the space-age technology that portrays vast areas of the Arctic at a glance, is making possible the most detailed picture of the North ever created. While the primary focus of Scientists at the Top of the World is the scientists and their work on the land with local people, this is not the only content. The film also shows scenes of the North that take one’s breath away. It is a stunningly beautiful part of Canada and of the world and difficult to imagine without glacial ice and snow and the plants and animals that have adapted to living above the 60th. Highly Recommended. Barbara McMillan is a teacher educator and a professor of science education in the Faculty of Education, the University of Manitoba.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- April 24, 2015. |