| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 27. . . .March 20, 2015

excerpt:

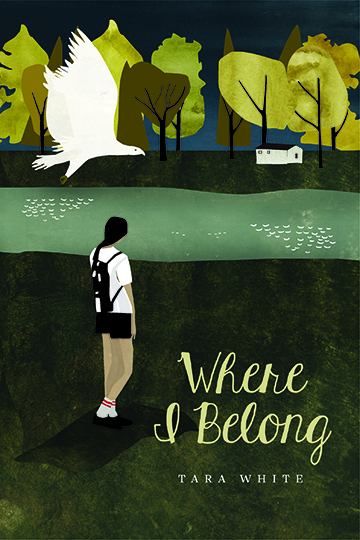

It’s the summer of 1990, and Carrie Stowe lives in McDonalds Corners, a small Ontario town within a few hours of the provincial border of Quebec. She’s lived there with her physician parents since infancy: “I always knew I was adopted. I never thought too much about it. As the only black haired, dark skinned girl in town, I was used to feeling different.” (p. 11) May is hockey playoff time, and in most small towns throughout Canada, tournaments are major social events. For high school girls, they are an all important opportunity to check out cute guys. Carrie’s parents aren’t thrilled at the idea of their daughter missing out on an opportunity to study for upcoming final exams. As well educated professionals, it’s clear that they have ambitions for her and are highly protective. As Carrie sees it, they want her to be “a nun. A doctor nun.” (p. 16) Still, Carrie manages to escape and heads off to the game with her best friend, Dana. When a team of hockey players piles out of their bus, Carrie is rivetted by the sight of one young man, in particular. He’s very good looking, and, as she takes in all the details, she realizes he’s not just the man of her dreams, he’s “the guy from my dream!” (p. 19), a dream of someone to whom she feels “connected . . . by an invisible string.” (p. 14) Like Carrie, the boys on that team bus are all black haired and brown skinned. And in one of those fairytale romance moments, Tommy, the guy from her dream, stops to talk with her before boarding the bus back home to Akwesasne, the Mohawk reserve near Cornwall, ON. Tommy is handsome, charming, and like any prince, he says good bye with a kiss, tucking a note with his phone number into her jacket pocket. Wow! But, her parents are waiting in the parking lot, see it all, and Carrie is busted. The ride home with them is an inquisition, peppered with reminders about her upcoming attendance at a summer science camp, a necessity for students with medical school hopes. Like any teenaged girl, Carrie is furious at her parents’ well intended interference, and, as she drives home with them, “the feeling that [she] didn’t belong in this family was getting stronger by the minute.” (p. 24) That night, she has another dream, but it’s not about Tommy; it’s a dream about the man with a gun, one of many recurring dreams of violence in which she, or someone close to her, is threatened. At breakfast the next morning, she asks her parents about her adoption, expresses her curiosity about her birth parents, and her feelings of just not fitting in with the folks in McDonalds Corners. As far as the Drs. Stowe are concerned, she’s their daughter, they love her dearly, and just don’t understand the source of her discontent. So, after summoning her courage, Carrie calls Tommy and arranges to meet him at the mall. But, before she does, she heads off the school library and does a bit of research on the Mohawks. Typical of the 1990’s, the library’s collection is not exactly up to date on Native issues; even Ms. Cook, the bespectacled teacher librarian with appalling fashion sense, admits that the book Carrie has selected is “really old”. But, lacking anything else in the collection, Carrie checks out a dictionary of Indian tribes; the author states that “the word Mohawk meant ‘man eaters’. There was a drawing of a brown man with an evil smile on his face and a thick strip of hair, holding up a scalp in one hand and a knife dripping with blood in the other.” (p. 37) It’s a gruesome stereotype from a time long past, or so one would hope. One of the best scenes in the novel follows Carrie’s date with Tommy. Of course, she’s told her parents that she’s gone shopping with Dana at the mall in Perth. But, a lack of full shopping bags leads quickly to the revelation that one of her mom’s patients saw Carrie walking through the park with a tall boy. To her credit, Carrie doesn’t try to lie her way out of the situation, but her mom and dad are outraged, her telephone and television are unplugged, and Carrie is grounded, “forever”. At this point, she decides, “It’s time to do something radical”, (p. 41) and after experiencing another of her frightening premonitory dreams, she has a plan. She sees Tommy as the key to finding out who she really is, and after her last exam, she’s going to take all her savings, hop on the Greyhound to Cornwall, and get in touch with him. Of course, she’s confided her plan to Dana, who is loyal to a fault, and the best girlfriends head off together. But, the plan is thwarted at the bus station by a policeman holding a “missing persons” flyer, and the girl on the poster, Jessica, looks exactly like Carrie. And, so, through the intervention of a social worker from the Children’s Aid, Carrie finally does meet her biological father (her mother died in an accident, shortly after her birth ), her twin sister, Jessica, and the rest of her extended family. She spends time with them, growing close to her grandmother, who teaches her to make cornbread, while teaching Carrie the language, stories, and traditions of the Mohawk. Still, Carrie’s disturbing dreams continue, and then, as the Mohawk Nation blockades the highway in Kahnawake, the entire Oka crisis erupts, and all the violent images of Carrie’s dreams finally come together. And while the political crisis continues, Carrie’s grandmother suffers a medical crisis. Carrie quickly realizes that her grandmother, who understands the power of dreams and who tells Carrie that “the dreams are a gift from [her] ancestors. “(p. 95), has gone into diabetic shock. Only insulin can save her, and daringly, Carrie and Jessica drive through the forest, evading the roadblock, and reach Chateauguay where Carrie’s mom is staying. Dr. Stowe saves Gramma, and then Carrie heads out to fight for her people. But, rather surprisingly, there’s a happy ending. At the end of the story, Carrie realizes that “Kahnawake or McDonalds Corners, it doesn’t matter. As long as I have the love of family, my entire family, I will always be exactly where I belong.” (p. 109) How fortunate she is, to have come to such an understanding. Where I Belong is a short novel (109 pages), but Tara White manages to pull together a variety of issues: the identity crises experienced by Native children who were adopted by well meaning non Native families, the politics of Native land and culture which ultimately led to the Oka crisis, the prejudices faced by the Mohawk both in Canada and in the United States (where so many Mohawk worked on high rise construction as “sky walkers”), and the perpetuation of stereotypes by anachronistic educational materials, to name but a few. Some of the conflicts and issues (notably Carrie’s adoptive parents’ discomfort with her need to meet and connect with her biological family) were resolved too easily, I thought, but sometimes, a happy ending is a good thing. However, the authenticity of Carrie’s thoughts and voice pull it all together. She’s like any teen, white or Native, who has a best friend to whom she can tell everything and who is incredibly loyal to her; who has parents who know what’s best for her and who unwittingly embarrass her in front of her friends; and who is swept off her feet by an incredibly dreamy guy. And she’s also a young woman with the insight to accept that she feels different and who has the courage to “do something radical” and find out where she belongs. This is a good, short novel for upper middle school and high school female readers. Young male readers aren’t going to enjoy all the BFF (best female friend) dialogue, and the hockey tournament is merely a means of introducing Carrie and Tommy. Where I Belong also provides backstory to the Oka crisis of decades past, and for readers in other parts of Canada who are unfamiliar with the Mohawk Nation and their struggles, the book provides an approachable introduction to that history. Where I Belong is a worthwhile acquisition for middle school and high school libraries, especially those looking to add fiction with a Native perspective to their collections. Recommended. A retired teacher-librarian, Joanne Peters lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- March 20, 2015. |