| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume xxi Number 25 . . . . March 6, 2015

excerpt:

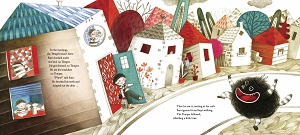

This review of Sam’s Pet Temper will be interpreted in light of the above considerations, but, before that, I commence with a summary of this new contribution to the repertoire (fiction) of Canadian children’s literature. Sam’s Pet Temper recounts the story of young Sam who found a new pet on the playground one afternoon when he could no longer wait his turn to enjoy the various apparatus that beckoned him. The pet that Sam found was a powerful something that was seething inside and was now released: his temper. Within seconds of its release, Sam’s temper, a black and furry, golliwog looking creature with a long, scarlet tongue, had cleared the playground, thus leaving the teeter-totter, slides and swings for Sam’s sole enjoyment. The illustration depicting the impact of Sam’s furry, frizzy, anthropomorphised, as well as zoologized, temper shows the cartoon-looking children of the playground, eyes agog, fleeing in fright in all directions. What ensures the characters’, as well as the readers’, fright is the illustrator’s— Arbona’s visual representation of the Temper: his frizzy, curly hair, blackness, round-button eyes, wide mouth, and intensely red tongue and wide mouth. As well, the terror of the children inside the story world and the real children who may view it in classrooms is assured by the particular interplay and contrast evoked by the colour of hair (black), eyes, tongue and inner mouth (blood red). He is scary-looking. The illustrator chose to render the Temper in a manner that makes the Temper something that should be, and would be, shunned by child readers and/or viewers. While it is generally true that we want children to resist giving into their tempers, the way the matter is handled in Sam’s Pet Temper is unfortunate. It is primarily the symbolizing of the Temper that is deeply problematic. The semiotics used by Arbona to symbolize the Temper appears to draws on, and summon, iconology of negativity. The Temper—this fictionalized zoological creature—is dreaded because of his size, his blackness and how this blackness is represented. The Temper is hideous. He frightens children. Few, if any, children would want to be him or be like him. This, of course, is the point the author wishes to make. The Temper is a powerful, negative force. For instance, when Sam sees the effectiveness of the Temper in getting him what he wants on the playground (the frightened children), he invites it home. Relishing his liberation and his ability to provoke fear and dread in other children, the “Temper bounded into Sam’s arms and licked him across the face” as indication of gratitude for the invitation. “The Temper was so funny! Sam knew they were going to be the best of friends.” Emboldened by his powerful Temper, Sam defied his mother when he arrives at home. The Temper kicked and slammed the door, kicked the wall. When reprimanded, Sam blamed his Temper for these actions and was reminded to “control his temper.” This was not easy to do, and by bedtime Sam wished he did not have a temper. However, it followed him to school the next day, created even more havoc and resulted in Sam’s early departure. Though he is reminded that he alone can “control” his temper, this is difficult for Sam until he begins to find it increasingly burdensome and embarrassing. It is then that Sam commences to employ temper controlling strategies learned from his father and his teacher. When Sam employed the strategy of saying the ABCs backward as his teacher had taught him,

Ultimately, Sam is able to control his “Terrible Temper” by reminding it that he is the “stronger”. He exercises this useful self-knowledge and power whilst taking a deep breaths and letting them out s-l-o-w-l-y.” With Sam’s using this strategy, the Temper was now “sitting at Sam’s feet” and under his control. Sam was now able to rejoin and engage in cooperative play with his playground friends. As for the Temper, he felt abandoned. He sulked in a corner until he spotted his next victim/friend—“a screaming toddler in a pink stroller.” Looking on and smiling knowingly, Sam realized that, if a “Temper ever found him again, he’d know what to do.” Sam’s Pet Temper is a book aimed at addressing an important theme in child development, but, ultimately, it is an overly-forceful work whose visual images may do more harm than good in contemporary classrooms in a diverse and plural society such as Canada. For this reviewer, Sam’s Pet Temper is unsettling on two accounts. The first is related to the over-the-top, historical, archetypal and unfortunate conflation of blackness with negativity, evil, and unpleasantness in a book intended for young children. The second is the explicit summoning and use of a major racist symbol/icon from the past—the Golliwog. Sam’s Pet Temper, as rendered by the illustrator, is archetypically a creature of low values, the lowest emotions, expressing Sam’s baser inclinations, the “dark side of the soul”—[Sam’s soul] (Fanon, 1967/2008). A tragic example of this can be seen on the double-page spread I have numbered page 21 and 22. Sam is seen desperately trying to regain control of, and over, the terrible, destructive thing that is now toppling his relationship with others and causing overall havoc in his world. This image is meant to scare children, and, in its golliwog hideousness, it is bound to do so. The fierce struggle we see between Sam and his temper from page 22-25 (based on the illustrator’s depiction) is a binary one that presents a battle between lightness /whiteness /brightness on one side and, on the other, darkness/blackness (the frightening golliwogish creature and his metamorphosis into a two-headed serpent (pp. 22-25). During this intense struggle between good and evil, whiteness and blackness, the fuzzy hair of the temper can be seen spreading into blackness “that thundered like a furious storm cloud” and that threatened the safety of the frightened children on the playground (pp. 25-26). Based on the visual images deployed, the foregoing pages can be read as a struggle between the moral side of Sam and his immoral, dark side. In this struggle over moral consciousness, our hero must be, and is, victorious as is indicated on page 27 where Sam towers over his now tamed and under control Temper—a diminutive, closed mouth golliwogish creature. The next page shows Sam, now a more morally conscious child, having a “wonderful afternoon” playing and collaborating with other children on the playground. To what extent does this literary work for children fit the description that children’s literature is, or can be, a highly influential moral technology? My answer is this: while children’s literature can be an influential moral technology, we need to consider the orientation of that technology and the interests it serves. Sam’s Pet Temper is a deeply disturbing book whose regrettable visual images of the Temper have the potential of doing great harm to the self-esteem and concept of black children, and this should be of concern for all who value respectful and dignified representation of self and Other. Furthermore, as indicated earlier, the book, Sam’s Pet Temper is unsettling because it summons and/or appears to be informed by a hurtful, pejorative racial iconology—that of the Golliwog (originally spelled Golliwogg). In an article posted on the site of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorobilia (http://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/), Pilgrim (2000) explains that the Golliwog “is the least known of the major anti-black caricatures in the United States” and “began life as a story character created by Florence Kate Upton” in 1895. Pilgrim adds that, “Golliwogs are grotesque creatures with very dark, often jet black skin, large white-rimmed eyes, red or white clown lips, and wild, frizzy hair” (para. 1). This is very similar to the image Arbona illustrates of Sam’s temper on pages three to twenty-one in the picture book. And if there is any doubt about the disturbing nature of the Golliwog, Pilgrim cites Johnson (n.d.) who reports that whilst reminiscing about the doll (the Golliwog) she created, Upton had this to say, “and before he had become a personality … We knew he was ugly!” The manner in which the Temper is symbolically expressed is disturbing. And it is this that matters: the outcome; the impact of the book on its audience--children. It contributes little to the well-being of children. Certainly the zoological construction of Arbona is not something any child would want to be or to be associated with … What will be the reaction of black children if this image is presented to them in a picture book? Citing considerable research evidence, Roberts (2004) points out “during the 1960s, studies consistently concluded that most Black children internalized the negative evaluations of their race perpetuated by the larger white society (in toys, books, and television programming), and thus developed lower self-concepts than white children” (p. 137). Likewise, Pilgrim (2000/2012) informs us the “campaign to ban Golliwogs in the United Kingdom was similar to the American campaign against Little Black Sambo—it was launched because “racial minorities and sympathetic whites argued that these images demeaned blacks and hurt the psyches of minority children” (n. p.). Therefore, for reasons outlined above in this paper, I agree with Darcus Howe who states that “Golliwogs have gone and should stay gone” (Pilgrim). Visual allusions and/or representations of golliwog imagery and iconology have no place in literature for young children. Through its illustrations, Sam’s Pet Temper commemorates this caricature by summoning negative icons and imagery in the character of the Temper as a Golliwogish creature. Therefore, I cannot recommend Sam’s Pet Temper. Although we need books to teach about emotion socialization, this is not one of them. This possibility was disrupted by the illustrations--by what appears to be allusions to Golliwog iconology. Rachna Gilmore’s (1999), A Screaming Kind of Day and Fiddle Dancer by Wilfred Burton and Anne Patton (2007) are good Canadian choices to explore the theme of emotions and emotion socialization. They are affirming, and it is such literature that augers well for the use of children’s literature as a highly influential moral technology. Not Recommended.

Barbara McNeil is an Instructor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina in Regina, SK.

References Burton, W., Patton, A., & Farrell Racette, S. (2007). Fiddle Dancer. (Norman Gleury, Trans.). Saskatoon, SK: Gabriel Dumont Institute. *Eagleton, T. (1985-1986). “The Subject of Literature.” Cultural Critique, No. 2 (Winter, 1985-1986), pp. 95-104. Fanon, F. (2008). Black Skins, White Masks. (Richard Philcox, Trans.). New York: Grove Press. Fanon, F. (1967). Black Skins, White Masks. (Charles Lam Markmann, Trans.). New York: Grove Press. Gilmore, R., & Suave, G. (1999). A Screaming Kind of Day. Toronto, ON: Fitzhenry & Whiteside. Pilgrim, D. (2000/2012). The Golliwog Caricature. Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorobilia: “Using Objects of Intolerance to Teach Tolearance and Promote Social Justice, http://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/golliwog/ Roberts, E. M. (2004). “Through the Eyes of a Child: Representations of Blackness in Children’s Television Programming”. Race, Gender & Class, 11(2), 130-139.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

(Table of Contents for This Issue - March 6, 2015.)

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |

Children’s literature is a highly influential moral technology* that can be leveraged to entertain, inform, inspire, problem pose and problem solve. While it does so, this literature simultaneously assists in the construction and production of subjectivities (Eagleton). Children’s literature proposes ways of being, thinking, acting, feeling and valuing, and, as such, the impact of such literature on its intended recipients (primarily children) requires careful, compassionate, and nuanced emotional, social, cultural and political understanding of the sociohistorical context in which it produced and received. Since children’s literature is implicated in the construction and production of subjectivities, those who are privileged to select literature for children need to be mindful of the best interests of the children when deciding what to select and share with them.

Children’s literature is a highly influential moral technology* that can be leveraged to entertain, inform, inspire, problem pose and problem solve. While it does so, this literature simultaneously assists in the construction and production of subjectivities (Eagleton). Children’s literature proposes ways of being, thinking, acting, feeling and valuing, and, as such, the impact of such literature on its intended recipients (primarily children) requires careful, compassionate, and nuanced emotional, social, cultural and political understanding of the sociohistorical context in which it produced and received. Since children’s literature is implicated in the construction and production of subjectivities, those who are privileged to select literature for children need to be mindful of the best interests of the children when deciding what to select and share with them.