| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 24 . . . . February 27, 2015

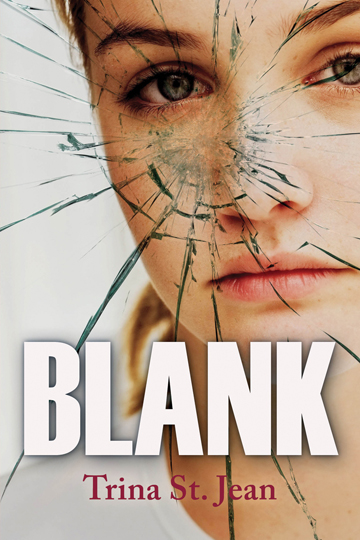

Blank is the first novel for writer and teacher Trina St. Jean who has a background in psychology. In her author’s note at the end of the book, St. Jean states that she wanted to explore the role “memory plays in our sense of self”. Jessica, the teenaged protagonist of Blank, struggles through most of the novel to determine how much she needs her memory to help define who she is and how she wants to live her life. When the novel opens, Jessica is in the hospital, recovering from a brain injury caused when a bison bull charged her on her family’s ranch. Not only can she not remember this traumatic event, she has retrograde amnesia, which means that she recalls very little of her life before it happened. After emerging from an 11-day coma, Jessica regains her physical strength fairly quickly but learns that she may never recover her memories. Jessica’s amnesia creates immense frustration for her and also for her parents. Although they are understandably relieved that their daughter survived such a devastating injury, they are saddened and confused by her inability to remember her life before it happened. It’s incredibly challenging for Jessica to try re-establishing relationships with her parents and friends. There’s an awkward scene in which her three best friends visit her in the hospital--and Jessica has to ask their names--that would be compelling reading for many teenagers. One spot of brightness in this dark time is Jessica’s little brother, Stephen, with whom she easily reconnects. The scenes involving the two siblings are perhaps the strongest and most engaging in the novel. Jessica’s detachment from herself is also troubling, both for her and for the reader: “I wonder what Jessica did when she couldn’t sleep in the middle of the night.” She frequently examines “the Girl in the Mirror” and wonders about what motivates her, what her personality traits are. Once back at home on her family’s ranch, she can search her room for evidence of the girl she used to be:

The “new” Jessica begins to question what the old Jessica valued, and she starts to suspect that perhaps she was too good to be true. She redefines herself in part by determining the ways in which she is different from the old Jessica. This focus on Jessica’s interior life is necessary to the novel’s development, but it may not be appealing for some readers. At times, I found myself not as sympathetic or connected to Jessica’s character as I had hoped to be, perhaps because her sense of self is not fully defined. I think Blank would appeal primarily to YA readers who are, themselves, very interested in the process of forming their own sense of self and who may have an interest in psychology. Teenagers don’t have to have amnesia to feel the need to break from whom they used to be and create a brand-new persona, even (or perhaps especially) if it’s not the persona their parents or friends are accustomed to. Blank contains some swearing and a party scene in which Jessica gets drunk. These factors, as well as an unconventional new friend for Jessica, help prevent the novel from seeming too “tame” for teen readers who prefer a bit of an edge to the fiction they read. Several of the scenes involving Jess and one or both of her parents are tense and realistic. The chapters are very short, and the novel is divided into three sections: Awake, Homecoming, and Surrender, which mark the stages of Jessica’s recovery from her injury. As Jessica gradually uncovers some of the details about the day of her accident, the pace picks up and the narration seems a bit tighter. St. Jean skillfully navigates a tricky ending that satisfies the reader without providing easy answers or clichéd wrap-ups. In the end, Blank does a nice job of teaching some lessons that apply to all of us, not just those who have suffered a brain injury. It reminds us about the power each of us has to form and re-form our identity and to move forward with the support of those who love us. Recommended. Gillian Lapenskie is a teacher-librarian at Barrie Central Collegiate in Barrie, ON.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home | Next Review | Table of Contents for This Issue - February 27, 2015 | Back Issues | Search | CM Archive | Profiles Archive |