| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XXI Number 23 . . . . February 20, 2015

excerpt:

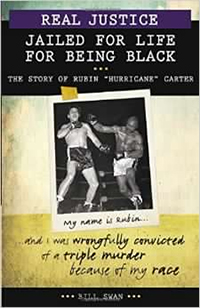

Following upon his earlier volumes on Steven Truscott, Real Justice: Fourteen and Sentenced to Death: The Story of Steven Truscott, and Donald Marshall, Jr., Real Justice: Convicted for Being Mi'Kmaq: The Story of Donald Marshall Jr., two Canadians who were wrongfully convicted, Bill Swan turns his considerable talents to the story of Rubin Carter, a professional African American boxer who was convicted with a friend, John Artis, of a triple murder that took place in Paterson, New Jersey in June 1966. Swan grabs the attention of readers from the beginning as he describes the shooting and introduces the first witnesses to the crime. He then details Carter's activities that night that culminated in his being stopped by police, brought to the crime scene and then questioned and detained for another half day before being released. Swan emphasized details and the untrustworthy nature of key witnesses that should have made a jury question the guilt of the two men. While the subtitle, Jailed for Life for Being Black, is sensational, Swan does set the context of 1960s America where racism remained blatant in policing and society. A black man driving a late model car was commonly pulled over for "Driving While Black." Sadly, this kind of racial profiling remains an issue in 2015, including in Canada where the controversial practice of "carding" by police has been demonstrated to be heavily targeted in Toronto towards black youth. Prior to returning to the tale of Carter's unjust conviction and long quest for exoneration, Swan provides a concise biography of Carter's complex early life. As demonstrated in the excerpt above, Carter had a lot of anger and frustration that manifested itself in physical fights and unlawful behaviour. When a corrupt official halted Carter's release from a reformatory, Carter left the institution and made his way to Philadelphia where he enrolled in the U.S. army as a paratrooper. It was in the army that he learned the sport of boxing with gloves and rules as distinct from street fighting. He also enrolled in speech therapy and began to learn from a Muslim friend that religion can bring one confidence. In describing Carter's short professional boxing career, Swan emphasizes the one, unsuccessful, attempt that Carter had to win the World Middleweight Championship in a bout against Joey Giardello in December 1964. Subsequent discussion of the trial that found Carter and Artis guilty of murder is certain to startle the reader who has been taught that the judicial systems in the U.S. and Canada are models of fairness and justice. Rather, it becomes clear that both the police and the prosecutors hate to admit when they make a mistake. Sometimes, they even conspire to twist facts in order to obtain a conviction. Despite sloppy policing, a failure to ensure that the jury was one of their peers (no African Americans served on the first trial) and key evidence came from a shady or untrustworthy witness, Carter and Artis were both convicted of three counts of first degree murder. The first appeal to the state's Supreme Court ended in July 1969 with the judge upholding the original verdict. In prison, Carter studied law and wrote The Sixteenth Round, an autobiography published in 1974. This book inspired others to take up Carter's cause, and they joined with an impressive list of supporters who raised funds for another challenge. Two key witnesses recanted their original testimony, but the trial judge dismissed this new evidence as unbelievable. Another appeal to the state's Supreme Court, however, found unanimously that Carter had not been treated fairly. A second trial was ordered. Witnesses changed their testimony, and Carter was found guilty a second time in the fall of 1976. After returning to prison, Carter maintained his innocence and focussed his energy on studying world religions and philosophy in a quest to understand himself and the meaning of life. The story of Lesra Martin, the suburban New York native adopted by Canadians living in a commune located in Toronto and the role that they all played in the successful appeal of Carter's case to the United States Supreme Court in 1985, has been told in the book Lazarus and the Hurricane and in Norman Jewison's 1999 film The Hurricane that also draws upon Carter's earlier life as told in The Sixteenth Round. The judgement ruled that Carter's rights had been violated in both trials, and he was freed pending appeal. The New Jersey prosecutors took another two and a half years before deciding not to seek a third trial. Carter moved to Canada and devoted his final years to working for the defence of others wrongfully committed in Canada and the United States, including Guy Paul Morin and others whose stories are told in other volumes of the "Real Justice" series. In the foreword, Ken Klonsky who helped Carter write his second volume of autobiography, Eye of the Hurricane, notes that even in his last days of life (Carter died from cancer in April 2014), Carter was writing letters in support of an individual that he believed was wrongfully convicted. Students interested in the law or social justice will not be disappointed by this book. The brevity of chapters, judicious use of recreated dialogue, inclusion of two pages of photographs and a map of some key sites in Paterson should appeal to the intended audience. A glossary and name laden index may be of some value. More useful is the list of additional sources that includes YouTube videos featuring some of Carter's boxing fights (some of the videos are no longer available), several interviews and an address by Carter, two websites concerning the wrongfully convicted, and Lesra Martin's site promoting his motivational speaking. In the end, Jailed for Life for Being Black is an inspiring, balanced portrait of a complex but inspiring man and the injustice that cost him two decades of freedom. Ironically, he may never have found his calling if he had not been denied a fair trial and wrongfully convicted. Recommended. Val Ken Lem is a collections librarian at Ryerson University in Toronto, ON. Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- February 20, 2015. |