| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 2. . . .September 12, 2014

excerpt:

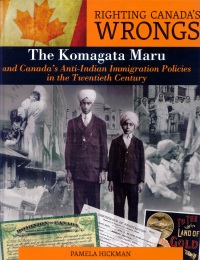

The year 2014 marks the centenary of the sailing of the Komagatu Maru. Carrying over 300 Indian citizens wishing to immigrate to Canada, the ship sailed from Hong Kong in 1914, destined for Vancouver, BC. As British subjects, Indians were supposed to have the right to travel to and to settle anywhere in the British Empire. But, like Chinese and Japanese immigrants to Canada, Indians faced a backlash of anti-Asian sentiment, and they were denied a series of fundamental rights, despite their status as British subjects. For nearly two months, the ship remained anchored offshore while government, legal and political figures argued over resolution of the case. Finally, a Canadian navy gunboat forced the ship to return to India, with tragic results for its passengers, upon its arrival. The third volume in Lorimer Publishing’s “Righting Canada’s Wrongs” series, The Komagata Maru, authored by Pamela Hickman, begins the story of the Indo-Canadian experience with a brief overview of Indian history, prior to the establishment of Britain’s East India Company, a monopoly which operated much as the Hudson’s Bay Company did in Canada. In addition to its mercantile ventures, the East India Company created a private army of Indian soldiers who served under British officers. These “sepoys” assisted the British in exerting ever-greater control over landowners and local authorities. However, the vast majority of Indians experienced increasing poverty, and, as a result, a general sense of injustice festered. By 1857, following a sepoy mutiny and a series of rebellions throughout northern and central India, the British Raj, or Kingdom, was established in India. While officers of the East India Company lived a very privileged life, rural Indians often faced extreme hardship and hunger, despite surpluses of food grain (bound for the export trade), within India. Not surprisingly, many Indians became economic immigrants, seeking work in other parts of Asia, or travelling as far as South Africa or the West Indies. As indentured labourers, their status was only marginally better than slavery, and they frequently suffered all manner of abuse and inhumane living conditions. Indian immigration to Canada began in the early 1900’s with the arrival of thousands of young men who had heard stories of a land of promise and opportunity. Like many nineteenth century immigrants, they found laboring jobs in the farming, fishing, and industrial sectors. It was a difficult existence: “they were housed in crowded, substandard housing and were often paid less than their white co-workers for the same jobs. . . . As time went on, some were able to start their own businesses and hire others from within their cultural community.” (p. 26) Of these early immigrants, some were Muslim, some Hindu, but the majority were Sikhs. The Sikh religion and culture was established in India’s Punjab region, and, by the seventeenth century, it had developed a strong spiritual identity; in Canada, Sikh immigrants built temples (Gurdwaras) to maintain that identity and provide a focal point for their community. And it was a largely male community; in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Canadian government passed a series of orders-in-council, halting any further immigration, including the wives and children of men already living in Canada. As a result, the Indian community in Canada became increasingly discontented, and its anger focused on Britain, the Empire, and the Raj. Just as anti-Asian sentiment found expression in Canadian organizations such as the Asiatic Exclusion League, Indians in Canada formed societies, such as Vancouver’s Khalsa Diwan Society, in order “to respond to ‘all the difficulties that confronted the Indians – Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims – relating to political, economic, social, and religious problems.’” (p. 44) News of Indo-Canadian activism spread to Indian émigrés living in other colonies, fueling the movement for an independent India. The test of Canada’s openness to Indian immigration came in December 1913, when Gurdit Singh, a Sikh businessman and supporter of the Indian independence movement, met with a group of frustrated Indian men at a Hong Kong Gurdwara. He chartered a Japanese-owned vessel, the Komagata Maru, and, by the time the ship had reached its last port, 376 passengers were on board and sailing for British Columbia. Singh stated, “If we are admitted, we will know that the Canadian government is just. If we are deported, we will sue the government and if we cannot obtain redress we will go back and take up the matter with the Indian government.” (p. 48) But the passengers were not allowed to land as either refugees or as immigrants, and except for 20 passengers who were returning to Canada, as well as the ship’s doctor and family, no one was allowed to leave. Two weeks after the ship anchored in Canadian waters, neither food nor water was provided to Komagata Maru passengers. Meanwhile, the Vancouver Indian community organized a “shore committee” to provide food and water and paid off the shipping agent in order to gain control of the charter. Two passengers were taken from the boat in order to be tried as a test case under the Immigration Act. The passengers lost the case, the boat was ordered to leave, and did so on July 23, 1914, having been provided only with water and no food. Rather than returning to Calcutta, as originally planned, it landed at a small town called Budge Budge (Baj-Baj) where violence ultimately erupted between passengers and police. Gurdit Singh went into hiding and remained so for many years. However, the return of the Komagata Maru had encouraged Indian dissent both in Canada and elsewhere in the Empire, and, as a result, in 1918, the Canadian government changed its immigration policy so that wives and children of Indian immigrants in Canada could finally come to Canada. Interestingly, the author notes that “when the women arrived, their husbands often insisted that they dress in Canadian-style clothes in public. Most young men got their hair cut, abandoned their turbans, and bought new clothes. . . . Trying to blend in was an attempt to reduce the racism, alienation, and fear that the new immigrants felt from the local population.” (p. 66) Few immigrated to Canada following 1918, but in 1947, after India’s independence, immigration to Canada grew slowly, and by 1967, following major changes to Canada’s immigration policy which focused on “personal characteristics of the immigrant, instead of on race and country of origin” (p. 74), Indian immigration increased enormously. The 2011 census now indicates that 1.1 million people of East Indian descent live in Canada with nearly half living in the Greater Toronto Area and one quarter living in BC (p. 84). The Indian community has made a concerted effort to maintain its culture and identity while sharing deeply in the life on Canada. There’s even a Punjabi broadcast of Hockey Night in Canada! The tradition of political activism has also continued, with some Canadian Sikhs being vocal supporters of Khalistan, an independent Sikh state in India (the 1947 independence resulted in the partition of India, splitting the state of Punjab, leaving Sikhs without a homeland). As with all political issues in any ethnic community, the Indo-Canadian community is divided on the subject of Khalistan, with some believing that the issue is past, while others believe that “My parents’ generation may have given up on Khalistan but mine hasn’t. Sikhs all over the world want it, including those in India. We’ll campaign for it always . . . peacefully, of course.” (p. 81) Since 1914, other boatloads of refugees have arrived on Canada’s shores: in 1987, 174 Sikh migrants arrived in a small Nova Scotia fishing village, having travelled illegally from India in order to escape anti-Sikh violence in their homeland, and, as recently as 2010, a boatload of Sri Lankan migrants arrived on the BC coast, fleeing civil war in their country. Canadian immigration laws cannot deny entry to refugees based on either their race or country of birth, but those claiming refugee status can be detained for indefinite amounts of time while the legitimacy of their claims is investigated. Those who are successful in claiming refugee status are accepted into Canada, and of those whose claim is rejected, deportation is often their fate. In 2006, descendants of Komagata Maru passengers met to begin the process of seeking an official apology and redress from the Canadian government, and in 2008, Liberal MP Ruby Dhalla tabled a motion in the House of Commons, a motion asking for an official apology. While Prime Minister Stephen Harper did make an apology at an Indo-Canadian festival event in August of 2008, because the apology did not take place in the House of Commons, some members of the Indo-Canadian community consider it insufficient. However, the Canadian government has funded many projects which are designed to provide public education of the event: memorials, plaques, artistic events and so on. Many Canadians know of the World War II internment of Japanese Canadians, and some may know of a similar injustice done to the Italian Canadian community during that time. 1914 also marks the centenary of Canada’s first internment operation when Ukrainian and other eastern European immigrants from territories which were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were interned as enemy aliens. The story of the Komagata Maru may be less well-known than the internments of World War II, but it is no less shameful, and it evidences that Canada does not always “embrace” its immigrants with open arms. The Komagata Maru does an excellent job of telling a regrettable story of injustice and government-legislated controls of immigration. Even more so than the previous two volumes in the “Righting Canada’s Wrongs” series, this book tells much of the story through presentation of a truly impressive collection of images, visual material, and video clips: the colour and black and white photos and the facsimiles of personal and government documents are richly captioned and hugely informative. Throughout the book, icons titled “Watch the Video” direct readers to excellent visual and audio content posted on the web-site, Komagata Maru: Continuing the Journey (http://www.komagatamarujourney.ca), as well as other web-based videos. A Timeline providing significant events in Indian and Indo-Canadian history, a Glossary of terms, and a listing of materials For Further Reading, all add to the book’s value as an acquisition for high school libraries and as a supplementary work for use in social studies classrooms. A most useful work, both as a source of information on the history of Indian immigration to Canada and of systemic discrimination, enacted by the government of Canada, based purely on ethnic intolerance. Highly Recommended. Joanne Peters, a retired high school teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- September 12, 2014. |