| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume xxi Number 15 . . . . December 12, 2014

excerpt:

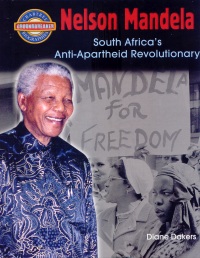

Nelson Mandela is the powerful story of the life and times of one of the twentieth century’s most decorated and acclaimed leaders. In a balanced and very readable narrative, Dakers shows the reader how “even a little boy from a tiny village that’s just a speck on a map in the wilds of Africa—has a voice in the world.” She emphasizes people and events who helped to shape Nelson Mandela into the man, activist and statesman that he became. Mandela was named Rolihlahla when he was born in a small South African village to the village chief and his third wife in July 1918. A change in family circumstance forced him to move with his mother to her family’s nearby village. His mother enrolled him in the local British Methodist mission school where the teacher gave him the English name Nelson. A few years later when Mandela was 12, his father died, and Mandela moved to the home of the grand leader of the Thembu people, Chief Jongintaba Danlindyebo, who had agreed to become Mandela’s guardian. Watching how the Chief settled disputes in a way that respected everyone taught Mandela valuable lessons about leadership and its exercise. Daker describes in some detail the coming-of-age rituals that Nelson, then 16, and his male peers experienced. In explaining the customs of the people, often in side stories, Daker sensitively provides information on topics such as polygamy and arranged marriages. She introduces historical concepts, such as truth in oral history, and questions the reliability of written accounts. Numerous photographs in black and white illustrate the text appropriately. Mandela was sent to boarding schools where he met people from other tribes and was exposed to new ideas and leadership opportunities. Increasingly, he began to question his future in a country where a white minority held power over the black majority. Early political activism got him expelled from the University of Fort Hare where he was studying politics, Dutch law and other subjects. After running off to the city of Johannesburg, he eventually met Walter Sisulu and other influential people who would become colleagues in the quest to end state sanctioned racial discrimination in South Africa. Mandela worked as a clerk in a white law office and continued pursuing a university degree and eventually became a lawyer. In 1942 with Sisulu’s urging, Mandela joined the African National Congress, a political organization dedicated to uniting black Africans, improving their living conditions, and fighting racism. Soon he was a co-founder with Sisulu and others in the creation of the ANC Youth League that adopted a more radical stance. The success of a week-long boycott that was triggered by a huge increase in the fares of the buses that transported blacks from the township of Alexandra to downtown Johannesburg where they worked showed Mandela first-hand the power of a group of people united in a cause. Other events in the early 1940s reinforced this learning. However, things took a turn for the worse following the whites-only election of 1948 that brought to power the National Party that brought in apartheid laws making official previously unofficial rules that sought to separate whites from blacks and so-called colored peoples. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the ANC and its Youth League accelerated protests against racial discrimination by holding boycotts, rallies, strikes and other actions of peaceful civil disobedience. The government established stricter laws, continued arresting dissidents, and supported increasingly brutal policing. By 1953, Mandela admitted for the first time that nonviolence had been “a useless strategy” in the fight for equal rights. The radicalization of Mandela and other ANC leaders was accompanied by the installation in 1958 of an even more oppressive government. The requirement for black men and women to carry a pass to allow them to enter white areas of the country was met by the ANC and a rival protest group’s anti-pass campaigns. At Sharpeville, a township south of Johannesburg, police killed 69 and injured hundreds of other protesters on March 21, 1960 when they showed up at a local police station without their passes. As the situation deteriorated, Mandela and others took up more dangerous actions, such as bombing government property and sabotaging power plants, in an effort to cripple the government with a minimum of risk to civilians. While Mandela was back in prison in the summer of 1962 for political offenses, more serious charges were laid supported by evidence from his own diary outlining guerilla activities and bomb-making instructions. When the trial concluded two years later, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison and became the most famous prisoner at the maximum security prison on Robben Island. International pressure, along with local calls for freedom for Mandela and an end to apartheid, finally met success when Mandela and his peers were released in 1990. President de Klerk had been elected a few months previously with a mandate “to bring justice to all.” He abolished the apartheid laws and worked with Mandela to develop a new constitution that decreed that all citizens were equal. In 1994 when the nation held its first election under universal suffrage, Mandela’s ANC party won a large majority. Despite the emphasis on the political, Daker does not ignore the basic facts about Mandela’s families. His first wife, Evelyn, was not particularly interested in politics. They divorced after 14 years of marriage. Only one of their four children survives today. Mandela married Winnie shortly after his divorce. She was an enthusiastic supporter of the anti-apartheid movement and often served as a spokesperson when Nelson was in prison. Her troubled history and downfall is dealt with in a sympathetic manner. By the time Mandela was freed in February 1990, his marriage to Winnie was pretty much over. She had become involved with another man, and she and Mandela separated officially within a couple of years and divorced in 1996. Mandela was fortunate to find a third loving wife when he married Graça Machel in 1998. The volume includes a useful chronology, glossary and index. The list of further resources includes several age-appropriate books, some videos/dvds including (some freely available online) and five excellent websites. Minor complaints about the book include some repetition about Mandela’s multiple names and a failure to mention the role of the Truth and Reconciliation process in the early years of the post-apartheid nation. Highly Recommended.

Val Ken Lem is a librarian at Ryerson University in Toronto, ON.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

(Table of Contents for This Issue - December 15, 2014.)

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |