| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 7. . . .October 18, 2013

excerpt:

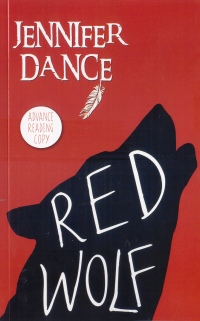

Jennifer Dance's Red Wolf is a heartrending, relentlessly compelling novel about the impact of the Indian Act of 1876 and the residential schools system upon indigenous cultures. She takes readers alongside Mishqua Ma'een'gun, or "Red Wolf", from the age of five, when his family goes onto a reserve, to his mid-teens when he is released from residential school. Dance is uniquely qualified to write this novel. In her "Dear Reader" letter at the beginning, she writes: "I first learned about Canada's residential school system in 1980. I was only 30, yet racial hatred had already touched my life, leaving me a widow with three mixed race children." Years later, when Dance's daughter married a "Status Indian", Dance was welcomed into her son-in-law's family, where she learned about First Nations cultures and school survivors. In writing Red Wolf, Dance worked with a Native consultant to ensure accuracy in her representations of the Anishnaabe language and culture. Red Wolf is set in Ontario in the 1880s, a time of settler expansion when Native people were being forced from the land. As the novel begins, a starving wolf cub with a crooked ear approaches an Anishnaabe camp. His pack members have been shot by "Uprights", as he calls human beings. A small native "Upright", Mishqua Ma'een'gun, befriends the wolf who becomes his part-time companion. Red Wolf's parents and their community are in the middle of a hard choice. A government agent comes to tell them that loggers will be coming to the area and that they should move onto the reserve where the government will provide money for food and education for their children. During the confrontation, five-year-old Red Wolf leads the agent's horse to better grass. For that, the agent labels him "Horse Thief" and develops an animosity toward him. Some of The People (as the Anishnaabe call themselves) stay to fight the loggers, others move to new hunting grounds, and some, like Red Wolf's parents, move to the reserve for the sake of the education being offered in order to fit their children for life in the "new world". Red Wolf's father has no idea that he will henceforth need a pass to leave the reserve, or that his son will be taken to a boarding school five days' journey from the reserve. Dance does an excellent job in presenting her novel from the Native point of view. Part of it is the depiction of the boy's confusion and terror as his braids are cut off and his hair is washed in kerosene by rough white people who bark at him in a foreign language. Red Wolf is given a number and a new name, George. Dance shows, too, how harsh treatment and loneliness damage the child's self-confidence. Red Wolf wonders if his family can no longer feed him, or if they took him to school because of his mild jealousy of the new baby. Dance's skill in structuring a novel helps her show the spiritual richness of Red Wolf's culture. Several times, in crises, Red Wolf thinks or dreams of his grandfather's stories about the origin of the world and the cycles of life. In contrast, the Christianity taught at the school is confusing and problematic to the little boy. Watching a school Nativity play, Red Wolf does not realize that "the boy in blue was supposed to be the mother of Jesus, and that the boxes that the wise men carried were empty." Here, the child's innocent observation contains another level of meaning. On returning to his parents for the summer, Red Wolf has forgotten some of the People's language, and he cannot adequately describe the horrors of the school. He tells his father about Jesus: "He's dead. His head is on the wall at school." Red Wolf has also learned about Hell: "A big wiigwam [sic] under the earth... hot.. smells bad. The people cry forever." His father asks, logically, "Can they not throw open the door flap?" When Red Wolf says no, they never get out, his father replies:

The wolf, Crooked Ear, who turns up when Red Wolf comes home for the summer, is a comfort, but the school becomes gradually worse. Thanks to the help of a white neighboring farmer, Red Wolf escapes, and when Crooked Ear appears and joins him on his journey, the reader thinks that his escape may be successful. The boy does get home, but before his father can organize a winter hideout for him, the police arrive to take him back. Red Wolf is angry at his father for not putting up a fight for him, and thenceforward, his spirit is broken. Dance's presentation of the European characters in the story is insightful. The couple who run the school under the supervision of Father Thomas are uneducated crude people who unquestioningly accept and perpetuate the stereotype of Native people as "filthy savages". The priest's cold objectivity is captured in the quote at the beginning of this review; the detail about the sticky sap suggests that he has blood on his hands. One of the teachers abuses a boy named Henry, who, in response, becomes the school bully. Through the Indian agent, the villain of the novel, readers get a hint of explanation for the white characters' brutality and lack of feeling. While tracking the escaped Red Wolf, the Indian agent admires the landscape for its cleanliness and beauty, "compared to the squalor of London... the one room his whole family had lived in, so close to the Thames that at low tide the stink of slimy mud pervaded even the smell of frying sausages...Never again would he doff his hat at landed gentry." Readers can see that the violence of an unequal, hierarchical society has made him a savage. Two white characters are more or less decent people, but they fail to help Red Wolf. One, the farmer who helps him escape, has observed and deplored the hard farm labor demanded of the children. Another farmer, who employs teenage Red Wolf as a farmhand, promises him his Clydesdale horse, but dies before he can put the gift in writing. Crooked Ear, the wolf, is the co-protagonist of the novel. Dance presents much of the story through his heart and mind as she does Red Wolf's. Crooked Ear is Red Wolf's friend, rather than his pet, because he has an independent life. Like the boy, he loses his family and has to struggle for acceptance within a group. Not only do boy and wolf share a spiritual bond, but there is also something mysterious and magical in the way Crooked Ear and his successor turn up when Red Wolf needs them most. Through Crooked Ear, Dance conveys that The People, and indeed, all people, have fuller and more spiritual lives living free in nature. "George's" best chance of becoming "Mishqua Ma'een'gun" again is to seek the help of one of the People who never went on a reserve. This possibility occurs to the reader during the boy's escape journey, but, because the author has more tragic historical truths to show, she postpones this chance of his recovery and healing for another fifty pages. As a mature reader who has read two recent adult nonfiction works about the residential schools (Speaking My Truth and Conversations with a Dead Man) I was surprised to find myself intensely emotionally involved with Dance's characters. My reaction is a compliment to Dance’s skill as a novelist. Because the injustices that Red Wolf faces are so relentless that they might overwhelm a reader as young as nine, I would recommend the novel to ages 12 and up rather than the age group 9 to 13, which Dance says is her target audience. Also, the vocabulary and concepts are a bit advanced for a nine-year-old. (Example: "Before coming to school George would have empathized with the victimized bird and would have tried to stop the carnage, but his... childish desire to help the helpless and rectify injustice had been replaced with a cold neutrality.") I share Dance's hope that her book will be used in schools to "increase understanding and compassion" and will also have "a place in healing the lasting wounds of residential schools among survivors and their families." Highly Recommended. Ruth Latta's most recent youth novel is The Songcatcher and Me, (Ottawa, Baico, 2013, baico@bellnet.ca or ruthlatta1@gmail.com).

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- October 18, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |