| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 37. . . .May 23, 2014

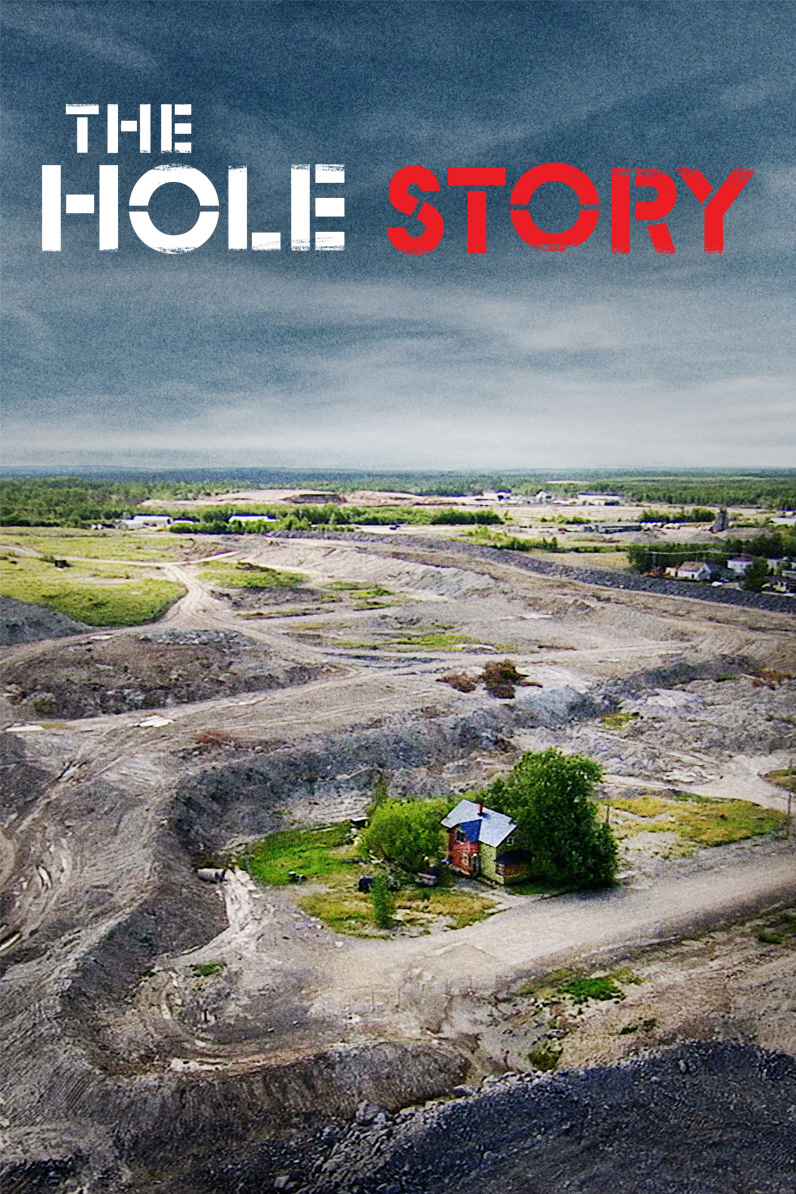

Unless one is celebrating a “hole in one” on the golf course, there is not much good in the word “hole”. “I have a hole in my sock”, “You have to get out of that apartment; it’s such a hole”, “What were you thinking? It’s like you have a hole in your head” “If you don’t dig yourself out of that hole, you’ll never get ahead.” So when Canadian mining is presented in the film entitled, The Hole Story, there should be no surprise that this is not going to be a kind look. What appears as a general history of mining in Ontario from the discovery of ore at Sudbury, then Cobalt and Timmins then west through Kirkland Lake and into Rouyn-Noranda, Val D’Or and Malartic Quebec, immediately becomes a condemnation of mining practices from the early years until the present. The film begins with the historical fact that much of Canada as we know it was owned by the Hudson Bay Company. The land was a source of great natural resources which were completely owned by a foreign company. The Native inhabitants were moved from their traditional lands and placed on reservations. The land exists for profit, and nothing and no one will get in the way of that. Things do not seem to have changed much over time. Canada is rich in mineral resources. Because much of the mining activity happens “north of cottage country and underground where no one wants to go”, many Canadians are unaware of its impact. Unless the price of gold increases or “there is a mining accident”, the mining industry stays under the radar. As the railroad went through what is now Sudbury, ON, a dynamite blast uncovered what looked to be “a major copper deposit”. Mining expertise was sorely lacking in Canada at the time, and so money poured in from Ohio, and the copper was sent to New Jersey for processing. Labourers from Europe came to Canada to work the mines “because no one else would do it.” Environmental laws did not exist, so, to remove the sulphur impurity from the copper ore, logs were coated with sulphur and set on fire: “the sulphur burned for months.” Sudbury had the only known deposit of nickel in the western world. No one much cared until the discovery that nickel combined with steel made stainless steel. When the United States went to war against Spain in Cuba in 1898, the new stainless steel clad ships were unsinkable. In this war and in the US war against Spain in the Philippines, “the navy did not lose a single ship. Nickel did the trick.” This newfound use for nickel was so attractive that “Germany offered to buy the entire production.” J. P. Morgan, the American industrialist whose financial holdings were “twelve times that of the American budget”, absorbed the Canadian Copper Company into the International Nickel Company or INCO: “America didn’t need an army to invade Canada; they did it with cash”. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier “was given a $1000 cheque as a personal dividend”. Shortly after the development of Sudbury, silver was discovered at Cobalt, ON. On 27 May 1906, The New York Times called Cobalt “the new El Dorado” and set off a “classic rush” bringing thousands of prospectors and adventurers from everywhere—even the Klondike which had been played out.” As silver is found mostly on the surface, mining did not require a major investment, and so “the poor Canadian capitalist could make their entry into the mining world and run it in English.” The workers, various ethnic groups of non-English speakers, were kept apart “to discourage any union attempts.” Workers were expecting to make “a bundle of cash and then return home.” The reality was “a 10 hour work day, for six and a half days a week. Working underground by candlelight, no ventilation, their lungs filled with dust from drilling, 40 per cent suffered from incurable silicosis. Fatal accidents, which occurred regularly, cost the mines a $100 fine. The life expectancy of a miner was 46 years.” According to the film, the silver from Cobalt was used by England to “fund its army’s occupation of India.” In 1909, the Cobalt Silver Kings defeated the Montreal Canadiens “on their home ice”. In July of the same year, “the town was burned, 1000 were afflicted by typhoid of which over 200 died.” To date, “2 million kilos of silver arsenic has seeped into Lake Temiskaming.” In 1909, another find—this time gold-- was uncovered in the Porcupine Camp. In 1913, Noah Timmins gave his name to the new town. From the three mines, Hollinger, MacIntyre and Dome alone, “seven times more gold was extracted than in all the Klondike—$100 billion in today’s dollars.” In 1912, when Hollinger imposed a wage cut on the workers, the surrounding 12 mines did the same. Five thousand men stopped working. This action was led by the Wobblies, “an American group determined to set up a union somewhere in the northern mining area.” The mining companies called in the Pinkerton Guards, an American private police force to break the strike. The strikers managed to block the railway from bringing in scabs, but they also blocked any supplies from coming in. Starving by winter’s end, “they went back to work. Many were deported. The mining industry could continue to prosper in peace.” During World War I, 80% of the world’s nickel came from Sudbury. Of that, “60% went to England and 40% went to Germany. Canadian soldiers at Vimy were being shot at by nickel plated bullets from their own mines.” In August 1916, “340 tons of Sudbury nickel was shipped to Germany by way of Baltimore.” By the end of the war, “Sudbury had been stripped of all its topsoil.” A returning soldier said, “It looks just like the battlefields overseas”. The Cadillac Fault stretches from Kirkland Lake, ON, to Malartic, PQ. Over “100 mines set up on both sides of the provincial border.” In 1926, the Quebec government “allowed the mining companies to control towns.” In the new town of Noranda, “the mine manager would act as mayor and police chief.” The Mining Act was rewritten to ensure “that no resident can claim damages caused by gasses or smoke produced during the operation of a smelting mill.” Noranda Mines claimed “soil, subsoil and air.” Quebec became “the best place to invest in mining. You can’t break the law, when you are the law! Those unable to find work in the mines “set up homes outside the mine concession thereby forming the town of Rouyn.” Gold producing areas never felt the depression. The harder the times, “gold becomes more attractive.” Strikes had been defeated in Kirkland Lake and Noranda. However, in the early 1930s, workers “were no longer satisfied with a Christmas turkey”, and they “began meeting openly to celebrate International Workers’ Day in Timmins.” A fire in the Hollinger mine earlier left 39 men dead. The closest mine rescue team was “In Pennsylvania—22 hours away.” The men were buried in a common grave. Still, “it would take another 15 years to form a union.” As new mines opened in the Sudbury area, “Germany remained a good client.” With the outbreak of World War II, Sudbury went into high production. Miners worked “seven days a week with every second Sunday off. Sudbury supplied 95% of the demand.” More nickel was extracted during the war “than in the first 55 years of their history.” In 1944, the Mine Mill and Smelter Union was accredited as “attitudes towards unions had softened.” So the bombs that dropped on Dresden and Hiroshima were “coated with union nickel.” With nickel making its way into household appliances after the war, “INCO was able to set the world price.” Companies were “getting richer, but not sharing the wealth.” Mining companies began to look to “nondemocratic countries—Chile, Indonesia, Dominican Republic” to establish mines. Union activity focussed on safety issues in the mining industry. Clearly, there was a link “between cancer rates and silica dust.” Safety standards came into place. Compensation was given to widows to the amount of “$500 million”. In 1973, “INCO owed $300 million to the Canadian government. While it paid out $300 million to shareholders, payout of the taxes was systematically deferred from year to year—earning them the title of ‘corporate bums.’” INCO only paid its municipal taxes to the city of Sudbury in the mid 1970s and “only on the value of the buildings on their land—a practice still in place today.” John Rodriguez, Mayor of Sudbury, admits that he has to go to the mining companies “begging for funds.” He condemns the “spineless Canadian governments who allow foreign companies to come in.” In 2006, Vale from Brazil took over INCO, and Extrata from Switzerland took over Falconbridge. Federal Member of Parliament Charlie Angus states that Canada “lost a great opportunity” in not combining both companies under a Canadian flag. Historian Benoit Beaudry admits that, “when shareholders are offered 30-40% on their shares, Canadian pride goes out the window and Quebecois pride could do the same.” In 2009, after Vale demanded a radical overhaul of the collective agreement, the workers voted to strike--the first in 60 years. The mine production was not affected as former Ontario premier Mike Harris passed legislation 10 years earlier that allowed for the use of scab labour. The Union force of 18,000 in 1969 was now at 3000. After 10 months, “a Brazilian company was able to tear up a collective agreement in a time of collective indifference.” Extrata now sends its ore to Norway for processing, and Vale sends its to Wales. Sudbury Mayor John Rodriquez states, “Private ownership means they can do whatever the fuck they want and whenever they want to do it. They take the resources out and we get the crumbs.” Until 1979, the law prevented anyone from suing INCO for environmental damage. In Val D’Or, in the event of a sulphur leak, residents are advised to “go indoors, seal up all openings and watch tv. The heavy metals in the air are being found in blood levels, and sulphur residue appears in the foundation of houses. The soil has been removed twice in 20 years.” No one wants to talk about it with “jobs at $30 per hour”. The town’s medical officer admits, “You can’t shut down 500 jobs—unemployment would be a bigger health risk than the exposure to arsenic.”. Many mines still leeching poisons into the environment have been abandoned with the owners “nowhere to be found”. The largest chemical dump in North America “lies between Rouyn and Val D’Or.” Mining practices have changed claims Louise Grondin, VP Environment and Sustainable Development, Golden Mines, Agnico-Eagle: “Mining companies do good things for the environment. We must stop bringing up images of the past.” True, mining has changed. Fewer workers are required. The work is not as physically demanding. The pay is good. Unions are not required. The environment is supposedly being rehabilitated. The film shows, however, that even this rehabilitation could prove disastrous in the future. In the town of Malartic, there is a hole where the houses used to be. Homeowners do not own mineral rights. Consequently, if the ground under one’s house shows promise, the houses can be moved, and they have been. The Hole Story is a condemnation of the mining industry in Canada, and its concerns can be applied world wide—especially as Canadian companies working abroad have taken advantage of lax laws in other countries. I grew up in Timmins, and my university costs were paid for by the money I made working at one of the local mines. It was not pleasant work, but I appreciate the work I was given. However, I found much of the content of this film both angering and shocking. Clearly, there is a bias in this film, but it does not pretend otherwise. All that the damage caused by mining for ore is now taking place in the oil and gas industries. The film serves as a warning, but fears we seem to be learning nothing. The Hole Story works on so many levels: as a history of the mining industry, a history of North Eastern Ontario and North Western Quebec, a history of the Union movement, the need for environmental protection, worker safety. It has great applicability in History, Geography, Geology, Civics, Science, Ethics, Environmental Science, Business, Media bias. It also serves as a warning regarding our treatment of the environment. No doubt this film could provide the basis for some very spirited debate. This is a long film, and it would be best shown and discussed in segments. The film should be required viewing for all Canadians (one f-bomb warning). Highly Recommended. Frank Loreto recently retired from his role as the teacher-librarian at St. Thomas Aquinas Secondary School in Brampton, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 23, 2014.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |