| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 35. . . .May 9, 2014

excerpt:

When you think of robots, it’s not likely the 12 “robo-animals” that author Helaine Becker describes in her newest book, Zoobots: Wild Robots Inspired by Real Animals. Unlike Pixar’s Wall-E, Star Wars’ R2D2, Zoomer the interactive rototic dog, and Honda’s humanoid, the robots Becker writes about have been developed to carry out tasks that humans can’t, and they mimic the physical characteristics of particular animals to do so. These animals include the bat described above, the pill bug with seven pairs of legs and overlapping scales of chitin, the octopus with boneless arms of muscle that act independently and can be strong and rigid or flimsy and soft, the cockroach with its tank-like build, 75 cm per second scuttle speed, and swarm intelligence, and jellyfish that also make use of collective intelligence and move through the oceans by expanding and contracting their bodies to push water behind them.

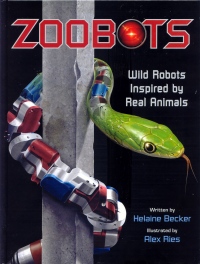

In the acknowledgements, Becker lists the university associated with the creation of each zoobot. Only one of these is Canadian. The Nanobot, a working prototype, was developed in the NanoRobotics Laboratory at École Polytechnique de Montréal. Of the 12 zoobots featured by Becker, the Nanobot is the only hybrid of living and non-living components. It uses a flagellated bacterium, Serratia mercescens, and adds to each bacterium a number of “mini-machines.” Because colonies of these bacteria can communicate and act like a single organism, the human-made components enable them to deliver life-saving drugs through blood vessels, to build microscopic parts for computer components, and to detect nuclear leaks and leaks in spacecraft. Zoobots is 32 pages in length and includes a table of contents, a two-page spread for each robo-animal, glossary, index, and one page wherein Becker makes clear that the zoobots described are first generation animal robots, and she predicts what the future for roboticists and their animal-inspired robots may be. As surreal and amazing as Becker’s descriptions are, they come alive through the artwork of Alex Ries and the design of Julia Naimska. Each page is beautifully planned, laid out, and illustrated. Readers who pick up the book because of the transforming snake on the cover will be amazed by the detailed depiction of the Shrewbot (based on the Etruscan pigmy shrew), Stickybot III (based on the gecko), the Ghostbot (based on the black ghost knightfish), and others of these astonishing mechanical animals. Highly Recommended. Barbara McMillan is a teacher educator and a professor of science education in the Faculty of Education, the University of Manitoba.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 9, 2014.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

Designed by roboticists who integrate mechanical and electrical engineering with computer science, zoobots are created to address a specific need. These needs can be for surveillance and reconnaissance, to perform or assist emergency personnel in search and rescue operations, for marine and terrestrial exploration and research, to inspect materials for flaws or damage, to perform delicate surgical procedures and operations, to fight forest fires, and to detect nuclear fallout, biological weapons, and toxic gases. One example is a serpentine zoobot, named Uncle Sam, developed by roboticists at Carnegie Mellon Biorobotics Lab in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It is built from indestructible, repeating, sensor laden parts, much like the links in a chain, that can be added or removed, and a “head” that incorporates a camera “eye”. As a result, it moves like a snake and can climb inside hollow pipes and ductwork, search for and locate trapped earthquake victims, perform surgical operations on human organs, and lift and place heavy parts on assembly lines. Even more amazing, Becker writes, is its ability to put itself together in the field.

Designed by roboticists who integrate mechanical and electrical engineering with computer science, zoobots are created to address a specific need. These needs can be for surveillance and reconnaissance, to perform or assist emergency personnel in search and rescue operations, for marine and terrestrial exploration and research, to inspect materials for flaws or damage, to perform delicate surgical procedures and operations, to fight forest fires, and to detect nuclear fallout, biological weapons, and toxic gases. One example is a serpentine zoobot, named Uncle Sam, developed by roboticists at Carnegie Mellon Biorobotics Lab in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It is built from indestructible, repeating, sensor laden parts, much like the links in a chain, that can be added or removed, and a “head” that incorporates a camera “eye”. As a result, it moves like a snake and can climb inside hollow pipes and ductwork, search for and locate trapped earthquake victims, perform surgical operations on human organs, and lift and place heavy parts on assembly lines. Even more amazing, Becker writes, is its ability to put itself together in the field.