| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 35. . . .May 9, 2014

excerpt:

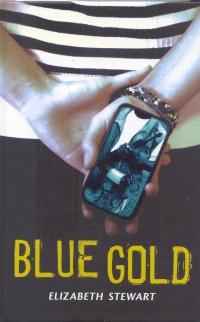

In this compelling story of injustice, the lives of three 15-year-old girls on three continents are wound together with the issue of how cell phones are made. Chinese Laiping moves from the country to the city to work at a factory job where cell phones are produced in order to better herself and help out her poverty stricken family. There, the company takes advantage of its desperate workers, withholding pay, abusing them on the factory line and demanding 12 hour shifts. After her father has a heart attack, Laiping is frantic for the money owed to her and begins to see the point of union rabble-rousers who are demanding better working conditions while they are beaten and dragged off to prison. However, she realizes that she will have to stay clear of them as she must keep her job to support her parents. African Sylvie and her family are in a refugee camp in Tanzania after fleeing the fighting in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Her father has been murdered over the mining of coltran for cell phones, and, because her mother is incapacitated by grief, it falls to Sylvie to take on the parent role. She makes sure that she and her younger brothers get to school, that she collects all the food supplies and cooks all the meals, and keeps her little sister safe. All this in spite of her being raped and facially mutilated when she was 10-years-old. But the family is slowly starving as the arrival of more and more refugees means that the same amount of food has to do for all. To Sylvie’s horror, her brother Olivier joins the camp warlord and gives Sylvie to this villain in marriage. With the help of the medical personnel in the camp, Sylvie and her family escape to the Canadian embassy where the staff generate so much media attention that Sylvie and her family eventually are permitted to immigrate to Montreal. Canadian Fiona leads a life of privilege in a wealthy area of Vancouver. She stupidly sexts a photo of herself to her boyfriend, Ryan, and then she has to deal with the fallout as the photo is posted online for all to see. In spite of her telling both her parents and her school principal, about the photo, Fiona insists on dealing with it on her own. Later, she discovers that it was really her stepbrother, not Ryan, who posted the photo, and so she posts that Ryan is not responsible but is, in fact, a good guy and to please do the decent thing and stop re-posting the embarrassing photo. She becomes drawn in to Sylvie’s story online and convinces her father, a big-shot mining executive, (whose company apparently does operate within guidelines) to use his influence to get Sylvie and her family to Canada. The main characters of Laiping, Sylvie and Fiona are all fascinating and realistic. Fiona’s idiocy and determination to act on her own without adult help is typical of Canadian teenagers. Her separated family situation is common, and she easily takes on the responsibility of a summer job, doing well at school and connecting with her step-siblings, negotiating with her powerful father over a new cell phone and being supported by all her girlfriends. Laiping’s fear and trepidation is artfully combined with her excitement over changing her life. An only child, her life is steeped in family obligation, and she endures awful verbal abuse, exhausting working conditions and arbitrary rules to help her mother and father. Like girls everywhere, she longs for the friendship of other girls and is attracted to the handsome, enigmatic anti-corruption boy who risks his life to improve the lives of others. Sylvie’s refugee camp life is all too normal in Africa, but she copes with it by remembering her father’s strong convictions and love. She actively tries to create a future in which she and her family will be safe, conscientiously going to a school that she knows is inferior, keeping track of her brothers, working at the camp medical clinic and staying away from trouble so she will not be raped again. She dares to dream of becoming a nurse or doctor and insists that she will not go to Canada without her entire family as she has promised never to leave them. In spite of suffocating memories, she gathers the courage to tell her story on video so that she might escape the horrors of war in Africa. Secondary characters, like Kai, the workers’ rights advocate, Fiona’s father and Laiping’s friend Fen, are compelling in their own way and provide depth to the stories. The story is told in alternating chapters, with more chapters dedicated to Laiping and to Sylvie than to Fiona. The dialogue is particularly well done with the voice of each girl coming through clearly. Although there is some telling, the author usually relies on action and dialogue to move the story along. There are some unrealistic moments, such as the idea that Fiona receives the cell phone with Laiping’s photo in it. It is a little too facile, also, that Fiona gets over the embarrassing photo so easily when, in the news lately, Canadians have been horror-struck at the suicides of girls in similar positions. There is an unfortunate implication that, if only these girls had told someone and been more determined to confront their bullies as Fiona does, disaster would have been circumvented. The responsibility of the bullies in these situations is not addressed in a telling manner. It is also unlikely that Sylvie’s family would have been brought to Canada so quickly in spite of the completely realistic influence of powerful executives and the overwhelming media blitz. However, the worldwide influence of the Internet, with Sylvie’s case coming to the attention of Fiona, and the Chinese blockage of internet sites, is well done. The message that an ordinary teen like Fiona can use the Internet and her father to influence world events will not be lost on the intended reader. The themes of sexual assault, worker’s rights, war, bullying and refugee life will resonate with both boys and girls. Recommended. Joan Marshall is a Winnipeg, MB, bookseller.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 9, 2014.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |