| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XX Number 3 . . . . September 20, 2013

excerpt:

Ged Martin is a respected historian who has previously written works on the origins of Canadian Confederation and on Macdonald's relations with the voters of Kingston, ON. This background makes him an authoritative voice and appropriate author for this biography. Martin brings fresh insight into the narrative that may correct earlier descriptions of the people and events in Macdonald's life. Martin should be congratulated for concisely describing the socio-political conditions of the time and emphasizing that readers try to judge Macdonald by the values of his era and not our own. His explanations of the evolving electoral system and the nature of nineteenth century politics are enlightening. In the introduction he writes:

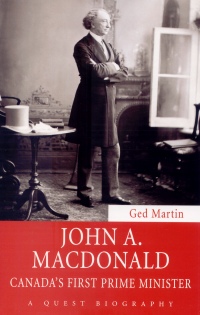

Born in Scotland in 1815, Macdonald moved to Canada with his family when he was five. They settled initially in Kingston, the community that would be central to most of Macdonald's business ventures and political career. The death of his brother left Macdonald as the only son to fulfill his parents' (especially his mother's) expectations and ambitions that he prosper in the new world, even though his father failed to do so. By the age of 15, he was apprenticed to a law clerk and went on to become a lawyer himself. Martin speculates that Macdonald's unfulfilled dream of obtaining a university education was one of the reasons for his drive to succeed. His militia service included combat against the Mackenzie-led rebels that shook the establishment in Upper Canada in 1837. Martin credits the Rebellion and Macdonald's experience of it for his recognition that Canadian society was fragile, and that "the art of government involved avoiding conflict among its contrasting elements – Tories and radicals, Catholics and Protestants, English and French." The biography is naturally heavily focused on politics, but aspects of Macdonald's personal life are developed. His marriage in 1843 to a cousin, Isabella Clark, was marked with sorrow. She was sickly, and their first-born son died in infancy. Macdonald had been elected an alderman in Kingston in 1843 and the following year as the Conservative member for the Kingston in the provincial assembly of Upper Canada. Themes begin to emerge including workaholic tendencies, commencement of binge drinking, efforts to be a good husband and emergence as a distant father from Hugh John who was born in 1850 and who would lose his mother seven years later. Macdonald remarried in 1867 to Agnes Bernard. Their only child, a daughter named Mary, was born in 1869 with a severe disability. Macdonald's abuse of alcohol likely inspired one writer's understatement that Agnes "had a good deal to put up with." The political world is portrayed as less than glorious, with dirty tricks being commonplace, including irregularities in voting rolls and complicated political games that are hard to grasp today. The nasty and unrelenting attacks by Liberal opponent George Brown in his newspaper The Globe led Macdonald and his supporters to establish their own papers in Toronto to counter the attacks. The use of mass media for political ends continues to evolve today. Macdonald exercised his considerable negotiating skills to convince four provinces to form a union as the Dominion of Canada. As the first prime minister of the new country, Macdonald continued to face opposition to Confederation in Nova Scotia. The Hudson's Bay Company's agreement to sell territorial rights to the vast Northwest to the Dominion government allowed the unstable young country to envision a vast westward expansion, but it didn't understand the aspirations of the Metis and aboriginal peoples in present day Manitoba. A promise to build a transcontinental railroad was the cost of getting the colony of British Columbia to join the Confederation. Macdonald's resignation due to the Pacific Scandal almost ended his political career, but his political comeback saw him engage in a new form of campaigning: the political picnic, the end to his alcohol abuse, and advocacy of a National Policy with protective tariffs against foreign made goods. The Riel Rebellion of 1885 and execution of Louis Riel created a deep divide that pit Francophone and Catholic Quebec against the Anglophone and largely Protestant provinces. His hope that ethnic and religious strife would fall away proved to be elusive. With no successor on the horizon, Macdonald continued to lead the Conservative government until his death following a series of strokes in 1891. Martin's balanced biography is a welcome addition to the growing body of work that is re-examining the life and legacy of Canada's first prime minister. The photographs, chronology and index are all adequate and familiar features of works in the series. Martin's decision to include a bibliography that records sources in short form is disappointing and likely confusing to readers, but perhaps understandable given the vast quantity of resources consulted. Highly Recommended. Val Ken Lem is the liaison librarian for History, English and Caribbean studies at Ryerson University in Toronto, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- September 20, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |