| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 6. . . .December 6, 2013

excerpt:

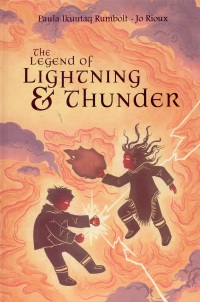

Paula Ikuutaq’s retelling of this legend opens with a celebration. It is spring, and Inuit people gather together in camps to sing, dance, and feast to share their happiness with each other. Two people, however, are not so happy. Orphaned siblings, a girl and her younger brother, have travelled a long way to join the camp, but they are shut out of the festivities on the grounds that there is not enough food to go around. Desperate and too hungry to travel further, these children become the first thieves when they steal hunks of caribou meat and wolf them down. Still hungry, they search the other families’ bags. Finding no more food, they search for toys to distract them from their hunger. The girl finds a piece of hairless caribou skin which she waves in the air and beats with her hand to make sounds. The boy finds a piece of flint and a rock, and he strikes them together to make sparks. When the brother realizes that the dances are over and their thefts will be uncovered soon, the sister knows they must hide or they will be punished. The boy suggests nine animals they could turn into, but the girl rejects each one and concludes that the only safe place is the sky. So they flee into the sky with their toys, and that, concludes an elder to her audience of children on the final page, is why we have thunder and lightning – because these orphans were neglected.

This tale comes from the traditional Inuit repertoire, and the illustrations pick up on the setting and cultural context by depicting the characters in their beautiful traditional dress (one woman has facial tattoos, a subtle detail) and emphasizing the natural setting. When the orphans consider the animals they could change into in order to hide, the animals they suggest appear as shadows, surrounding and visually representing how trapped the siblings feel. The illustrations are done in an appealing graphic novel style which adds to the emotional as well as natural landscape of the story. When the orphans are unable to find more food, for instance, the sister is drawn gnawing on her own hair in hunger and frustration. The sister, as the elder of the two, is more decisive, and the text states that her brother always obeys her. The illustrations depict the sister a few times in distinctly nurturing-mothering postures. The brother also has agency; he suggests ideas, notices the setting sun, and initially objects to her plan to flee into the sky. The text and illustrations work together to create a believable close sibling relationship. It is odd, however, that the tale is called The Legend of Lightning & Thunder, which gives lightning (the brother) primacy of place when most of the text suggests the reverse since it is the sister who has a (slightly) more active role – she finds her “toy” first, directs their course of action, and leads her brother into the sky. The only word that may confuse readers is “qulliq” which is not defined in the text or in a glossary. The illustrations depict a curved stone bowl holding a clear liquid. A simple web search revealed that a qulliq is an oil lamp made of soapstone carved in a crescent. Since qulliq is not defined in the book, curious readers may find this book a springboard for research about Inuit culture. Overall, The Legend of Lightning & Thunder is a lovely retelling of a myth that reveals a great deal about Inuit culture’s emphasis on caring for everyone, regardless of status, and an enjoyable picturebook to read. Recommended. Janet Eastwood is a student in the Master of Children’s Literature program at the University of British Columbia.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- December 6, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

The orphans are never identified by name or age, although the sister is two years older than her brother. The illustrations portray them as approximately ten and eight-years-old, give or take a few years. The story is told in third-person narrative, and on the final page the reader meets the narrator who, for the first time, uses the word “we”. The illustrations depict this narrator as an elderly Inuit woman in traditional dress, concluding her tale before five children (three girls, two boys) also in traditional dress. The illustrations pick up on this framing device quite well. This last page is a double-spread: on the left is an illustration of lightning streaking towards the ground outside a tent, while, on the right page, the elder and children are given little background so that the reader’s focus is drawn to their faces instead. The texture of the small amount of visible background hints that these characters are seated within the tent. The illustrations here also hint that, as this tale explains the cause of thunder and lightning, the demonstration of these phenomena outside the tent was the reason for the elder to tell her tale. This lends the story a strong sense of people and place.

The orphans are never identified by name or age, although the sister is two years older than her brother. The illustrations portray them as approximately ten and eight-years-old, give or take a few years. The story is told in third-person narrative, and on the final page the reader meets the narrator who, for the first time, uses the word “we”. The illustrations depict this narrator as an elderly Inuit woman in traditional dress, concluding her tale before five children (three girls, two boys) also in traditional dress. The illustrations pick up on this framing device quite well. This last page is a double-spread: on the left is an illustration of lightning streaking towards the ground outside a tent, while, on the right page, the elder and children are given little background so that the reader’s focus is drawn to their faces instead. The texture of the small amount of visible background hints that these characters are seated within the tent. The illustrations here also hint that, as this tale explains the cause of thunder and lightning, the demonstration of these phenomena outside the tent was the reason for the elder to tell her tale. This lends the story a strong sense of people and place.