| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XX Number 13 . . . . November 29, 2013

excerpt:

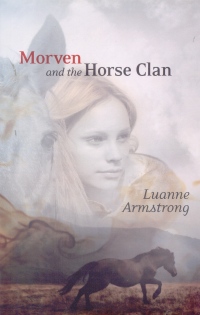

Morven and the Horse Clan is a work of prehistorical fiction, an adventure story set in 3500 B.C. Teenaged Morven lives in a hunter-gatherer clan on the plains of what is now Kazakhstan. Families within the clan are matrilineal, centring around a mother and her children, with the maternal uncle playing a provider/protector role. Fatherhood seems irrelevant. Morven has bright red hair like the northern people she has seen at a Gathering of the clans, but her two younger sisters are dark-haired like their mother, Botan. The nomadic clan migrates over the same territory, following the seasons. At clan council meetings, in which both men and women participate, discussion centres on where to go to escape the drought which is causing hunger. Although women hunt for small animals, there is a gendered division of labour in the clan, with the men hunting and the women staying in the camp to look after the children, clean hides, gather roots and berries, and prepare food. To her mother's consternation, Morven prefers the men's way of life. Her uncle, Nazar, says, "[S]he can learn both ways." Eventually, Morven's mother sends her out with her bow and arrow to hunt, saying that, although the men will not like having a girl along, her little sisters need more meat and fat than the men will give them. Morven comes upon a herd of wild horses and admires a young black stallion. On repeated visits to the horses she tames Black Horse and eventually gets on his back. She causes a sensation, riding him into camp. The clan members, particularly the men, want to hunt the horses for meat, but Morven tells them that the horse and his clan are now her friends and partners, and the horses will not be hunted any more. The men's circle insists that the horses are needed for food, but the shaman, Luz, tells them to leave her be and let her keep the black horse. The first fifty pages are about Morven's nonconformity with prescribed gender roles. As the novel goes on, readers encounter different peoples and different ways of life as author Armstrong depicts the clan's transition from the hunter-gatherer way of life to one of animal domestication and fixed settlements. When Morven goes scouting for a location where her clan can thrive and coexist with the horse clan, she encounters another kinship-grouping, a friendly people who live in wooden huts. They have more men than women, and few children. They are unfamiliar with tame horses. Morven decides to bring her clan to them so the wooden hut clan can "take us in and help us get strong again." A young man, Dura, accompanies her back to her clan, and, when Morven discourages his overtures, he mates with her friend, Lani, a young woman who seems destined to become a clan matriarch. Although some men want to eat the black horse prior to the move, Lani says no, that the horse can carry the children when they make the journey. The wooden hut people help Morven's clan survive and get stronger, but when Botan, her mother, discovers that this society survives by keeping their numbers down; that is, by killing girl infants through exposure to the elements, Morven's clan moves on. Once the clan is settled temporarily in a sheltered valley, Morven's mother and the other women ask her to tame more horses to help them with the load-carrying, which has hitherto been considered "women's work." When Botan dies, Luz, the shaman, praises her as "a leader among our people" and encourages Morven to take a new path in life. While hunting on horseback, Morven's clansmen encounter a people who live in one place which they call "Kazaan". The Kazaan people have houses with stone walls and wooden frames, wear bright clothes not made of animal skins and keep woolly horned animals in pens. They welcome Morven's clan with food served in "bowls carved out of wood with great care." Morven notes that "these people had the time to sit around and make beautiful things" and "the animals stank but their milk tasted good and the children in particular gulped it down." Kazaan men hunt. Women tend and herd the flocks, taking them out every day to graze and bringing them back to their enclosure every night. The women also gather plants and make clothes with the hair and wool of their animals. "In return," says Morven, "the people of Kazaan cared for these animals and kept them safe. It was like the bargain I had once had with the black horse, before he left me. These people hunted horses for food." Some Kazaan customs jar on Morven. In her clan, everything is shared, and everyone is part of a family. But Shuz, a herdswoman from another clan who ended up with the Kazaan, has not been accepted into any family. The Kazaans believe in private ownership. A group of their women, led by the first fat person Morven has ever seen, accuse Morven of stealing a bowl, and they go through the clan's encampment taking blankets, bowls, sticks and ropes. They make it clear that, if the clan needs more help, they will have to trade for it. To ensure her clan's survival, Morven unwillingly decides to tame horses, trade them for food and goods, and teach the Kazaan how to domesticate them. The Kazaan women see that domesticated horses would help them with carrying and hauling, but their young men are eager to ride. One youth, Kai, refuses to learn the taming process but jumps on a horse and gets thrown off. Later, after Morven successfully fights off his advances, Kai tells the elders that she made the horse throw him in an attempt to kill him. The Kazaan elders decide that Morven has "too much power" and that she and her people are "dangerous". They are afraid that the clan will someday try to take their land away from them. Soon Kazaan men with clubs keep Morven away from the horse corral.

When Morven's clan tries to take some horses and leave the Kazaans, violence erupts. In disrepute with both her clan and the Kazaans, and feeling guilty over enslaving the horses, Morven spends a winter camping alone except for a dog. Her mother appears to her in a vision, saying: "You changed the water's flow, my daughter. You brought a new thing into the world and no one knew how to think about this thing. Some people thought one way about it, some another, according to their natures. You did no wrong." In spring, returning to her clan, she finds a Gathering taking place, and a woman shaman, Elin, who invites her to study with her. The clans agree that the Kazaans are "cruel in their craziness." As the story closes, Morven's clan settles in a bowl shaped valley around a lake which they name "Botai" after Morven's mother. They construct log and stone houses with hides on top, trade for sheep and goats at the Gatherings, learn to spin and weave, and enjoy new foods like mares' milk. Near the end of the novel, a runner from another clan brings word that Kai, now calling himself Khan, is leading raids on the people of the plains, Morven rides out of camp on a golden horse to join him in uniting the plains people to fight the Khan. Luanne Armstrong deserves applause for creating a female protagonist who is not attracted to men, but prefers her own gender. Morven says, "I had no wish to be like Lani, surrounded by children, always either pregnant or nursing... I had never wanted this, had never felt the urges other women talked about... that compelled them to the sleeping robes with a man." Although Armstrong does not list the works she consulted while doing her research, a quick look at anthropological sources on the Internet indicates that her information about the domestication of horses is more or less correct. The March 6, 2009, issue of Science reported the findings of an international archaeological team led by the Universities of Exeter and Bristol, which traced horse domestication back to the Botai culture of Kazakhstan to 5,500 B.C. Analysis of ancient bone remains of horses showed "bit damage" to their teeth, indicating that they had been harnessed/bridled and ridden. Fats from horse milk were found in Botai pottery. Armstrong presents Morven's clan as adhering to a strict labour division, with hunting assigned to men and foraging, child rearing and chores assigned to women. Some scholars of prehistory hold that prehistoric women's participation in hunting was underestimated by earlier scientists. The very fertile stay-at-home type of woman, to which Morven refers, may have been a rarity among hunter-gatherers. The uncertainty of the food supply, with the consequent uneven nutrition, would affect fertility and infant mortality. It is impossible to know exactly when it was, back in the mists of time, that gender division of labour began, but the question has implications for present-day claims about the "natural" roles for women and men. Some anthropologists believe that the oppression of women, associated with the rise of private property, came more recently in history, with the shift from women-run collective soil-tilling to male-dominated plough agriculture. Novelists often take literary licence and compress a number of big changes into one character's lifetime. Authors of PF (prehistoric fiction) often research the customs of today's hunter-gatherers and semi-nomadic herders, and societies "discovered" by Europeans in the recent past. Then they extrapolate, imagining that the same customs prevailed in prehistoric societies. Prehistoric fiction (PF) is more like science fiction than like historical fiction. Both Sci-Fi and PF have a scientific basis, but each involves much speculation and imagination. Armstrong deserves applause not only for her unique heroine but also for taking on the challenged of writing PF. Recommended. Ruth Latta's most recent teen novel, The Songcatcher and Me (Ottawa, Baico, 2014, www.baico.ca), is set in 1957.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- November 29, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |