| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XX Number 13 . . . . November 29, 2013

excerpt:

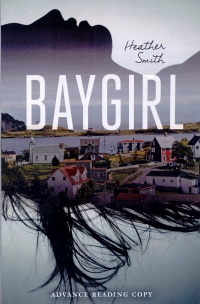

Taken from Baygirl, Heather Smith's timely new novel, the above excerpt offers an enticing fragment of a novel that I am eager to share with my students and one in which I am convinced many young adults are likely to find resonance, enjoyment and multiple opportunities for generating dialogue with self and others in literature circles or book discussion groups. This not soon forgotten book serves up a menu of plotlines relevant to today's young adults: alcoholism in the family, unemployment, the impact of residential and school mobility-feeling like a "teeny tiny fish in a humongous pond", rural versus urban binaries, starting over in a new place, first love, friendship, the othering of those who are not perceived to be from prestige locations or speak prestige varieties of English, and resilience and hope. Sitting at the juncture between historical and contemporary realism, Baygirl is, very much, a bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story that will captivate the attention of today's young adults. It is told from the perspective of 16-year-old Kit Ryan, a young woman from a scenic, fictional inlet community called Parson's Bay (Newfoundland). This well-crafted novel deals with the maturation and growing awareness of self and others. It succeeds in capturing the psychological, intellectual, and moral growth of a main character and her family when circumstances force them move and start over in a new location. The "colourful wooden homes of neighbours and friends" and the "steep, rugged cliffs" that flanked the inlet of this fishing community speak eloquently of the physical beauty of Kit's home town. This picturesque beauty, however, exists in juxtaposition with the material, psychological, and emotional turbulence that characterises the lives of many people in Parson's Bay after the provincial government found it necessary to "shut down the cod fishery" in 1992. The "fishing moratorium", as it was called, meant that there was "no fishing for two years." As a result, fishermen such as Kit's father, Alphonsus, and many like him from across Newfoundland lost their livelihood-the fishery-an institution that was the basis of their social and economic well-being for generations. One of the alluring aspects of this historically realistic novel is Smith's obvious insider-knowledge of the impact that the all-too-real moratorium on the cod fishery had on the lives of ordinary Newfoundlanders who depended on this natural resource for their livelihood. Smith is a Newfoundlander and appears to know much about what she writes. The plot, the dialogue, and shift from rural (Parson's Bay) to urban settings (St. John's) are expertly constructed and result in the unmistakable authentic feel of the novel as one about change, displacement, uprootedness and the impact of socio-economic change at the micro level-the personal lives of those affected. The impact of the change that hit Parson's Bay when the government made the decision to close the cod fishery is captured in the following:

The preceding speaks to the power of contemporary realistic fiction to depict reality in a manner that is compelling and full of resonance. The incident will come as no surprise to the many teens in Canada who live, have lived or are living with (an) alcoholic parent(s). In the above, Kit describes the scene that greets her regularly when she returns from school: her alcoholic father in a heightened state of inebriation. Seeing him in such a state fills Kit with disdain, disgust and lack of respect. Subsequently, the two enter a verbal tussle. On the surface, readers witness the teenage girl's shame and frustration at her drunken father and how drunkenness hobbles his comprehension of why she calls him a "friggin' loser." Beneath the surface of Kit's tongue lashing is a daughter's yearning for the sober, tender, dependable, and steady father she would like to have. Also beneath the surface is the father's equally strong need to be the reliable provider, guide and loving parent he hoped he would have been and a concomitant self-deprecation for not being the dreamed for and sought after ideal husband and father. Alcoholism fractures and fragments the fulfilment of these layers of yearnings and fantasies and unleashes a barrage of cutting words, outbursts of seething anger, and pain in Kit's family. It is in this morass of family misery that Emily, the wife and mother, agentically interjects a desperate action of intervention. She proposes that the family move away from Parson's Bay to St. John's in order to find employment and explore the possibility of rebuilding their lives after the closure of the cod fishery. The above complexities of the human condition are handled very well by author Heather Smith. She makes it clear that significant changes, such as the cod moratorium-the abrupt halting of a sociocultural practice on which economic well-being depended, are like death and can result in the accentuation of fragility and pre-existing social problems. This is evident in the progressive alcoholism of Kit's father, Alphonsus, when he was no longer able to fish and provide for his wife and daughter after the moratorium and in the similar reaction of her Uncle Iggy when his wife was suddenly killed. Equally true though in Smith's very engaging novel is the construction and development of characters whose words and actions make the strong suggestion that calamity, whether sudden or not, can accentuate and activate resilience and positive actions. I make these observations based on the behavioural change evidenced in Kit, her Uncle Iggy, and her mother. Contrastive to her husband, Emily, Kit's mother, is not downed by the calamity; she confronts it and maps an alternative storyline. Emily takes control of her family's material well-being by convincing her alcohol soaked husband and reticent teenage daughter to leave their much loved Parson's Bay and to move to St. John's. Once there, she wastes no time in finding employment and becomes the breadwinner and emotional anchor for Kit, her husband and her brother. As is illustrated in the preceding, Smith's characters undergo intellectual, psychological, spiritual and moral growth while they make their way through suffering, disappointments and pain. Though they experience painful episodes in their lives, characters such as Kit, her friend Caroline, Uncle Iggy, and mother Emily typify the full-heartedness and resiliency of most Newfoundlanders. They reciprocate and give back to suffering others as much and sometimes even more than they receive. They are responsive to each other's needs. This is one of the strong messages in the book and one that is bound to be of value to teen readers: we can endure, cope with, live through, and overcome painful episodes and thorny situations with the help of family, friends and community. The characters in Baygirl are not perfect; they make mistakes but are aided to strength and agency by their own inner resources and through the support and care of family and friends. Kit, for instance, is strengthened and grows in confidence by the loving and unfailing support she receives from her Uncle Iggy as he struggles out of the lead-like wet suit of alcoholism. As well, Kit is mentored and fathered by her grand-fatherly bluntly honest, hilariously funny and lonely, neighbour Mr. Adams. In addition to Mr. Adams, Kit is also sustained by and matures through her budding and hard-won relationship with Elliot, a teenage boy she meets at school in St. John's and with whom she eventually falls in love. Elliot is a good example of the kind of the balanced characters constructed by Smith. When we meet him, he performs masculinity in somewhat stereotypical ways (e.g., eagerness to help and impress an obviously new female student to the school with his "I know my way around here approach", his use of French, and the I am Mr. Popular, an announcement about having a girlfriend). However, Elliot is in the hands of a sensitive writer who understands the importance of constructing characters that are realistic yet not immune to social movements such as feminism and its impact on gender constructions in literature. Elliot undergoes change-and the prickly coming of age journey found in this piece of young adult literature. For instance, when Kit makes it clear that Elliot's advances are unwelcomed while he still has a girlfriend, the young man is forced to make moral choices. He is positioned to re-evaluate his tactics and strategies of courtship. He does have to choose. Predictably, Elliot eventually chooses Kit and reaches a level of maturity that sees him perform an admirable kind of masculinity and humanity through his decision to travel from St. John's to be with Kit while she and her father took care of her dying grandmother. Like Mr. Adams, Uncle Iggy, and even Alphonsus, Kit's father, most of the major and minor male characters in the book are constructed in complex ways that reveal their capacity for sensitivity, tenderness, emotional engagement and genuine concern for others-females as well as males. I appreciate this, and many young adult readers are likely to do so as well. That said, it is not only the male characters that are constructed with sensitivity, balance and complexity. Other examples of characters that are round, balanced and complex include Caroline, who befriends Kit at school, Emily who mediates the thick tension between Kit and her father, Alphonsus, and Nan, a loving grandmother who walks a delicate ethical line by avoiding condemnation of her son while providing a safe haven for Kit when she needs to get away from him. As a womanist/feminist educator and parent, I welcome such sturdy examples of female strength, grace, and humanity. They are mentors in print for adolescent readers. Along with offering up characters of depth and intrigue, as well as engaging plotlines, Baygirl is a special book for other reasons worth remarking. These reasons relate to Smith's inclusion and realistic portrayal of social schisms between urban and rural dwellers and issues relating to linguistic diversity-hot topics that are part of social discourses right across Canada. To illustrate, I point to the reaction of Amanda (Kit's antagonist) when the teacher introduces Kit to the class. "Amanda turned around and looked at [Kit] and said, "Oh, you're from the bay. No wonder you got lost. This school is probably as big as your whole town" (p. 85). Here Amanda, a self-nominated class bully and over-confident princess disparages and belittles Kit because of where she comes from-a small town, a less than prestigious social location from the perspective of the young urbanite. Kit feels compelled to defend her birthplace, but when she starts, Amanda cuts her off with this rock of hurt from her slingshot, "Oh, your accent" "It's so different ...", and this produced a few "giggles from the class." The linguistic incident described here is one that I experienced in school. It is also one that some of my former elementary and high school students experienced, is one experienced by some of my rural students today, and is definitely one frequently endured by many immigrants. Adolescent readers will not only empathize with Kit, they may find a sense of confirmation by the inclusion of such a realistically depicted scene. The encounter with such an incident in literature is one that may help victims of social stigmatization (based on birthplace, language and accent) see that they are not alone-they are not the only ones to experience such social sneers and jibes from members of dominant social and linguistic groups in schools and in society. The victims of such abuse may find comfort in the validation of their experiences and from Kit's ability to thrive in spite of such experiences. The preceding and other powerful scenes in the novel (e.g., Uncle Iggy's candid talk about his alcoholism and Kit's last conversation with her father) are believable, dramatic moments that can be fodder for teacher-led and intra-peer discussions about the systemic nature of othering, intergenerational alcoholism and issues of fathering. These teacher and peer-led discussions that the novel is likely to engender can open doorways that may help students understand that such problems cannot be solely located in individuals but are manifestations of structural and systemic problems at the macro level of society. Therefore, part of the charm and allure of this novel is its skilful depiction and stitching together of social and personal challenges in a believable ways. And this makes it ideal for book clubs and literature discussion groups inside and outside of schools. To conclude, Baygirl is a remarkable first novel that I vigorously recommend for students in Grade nine and up. I enjoyed it and will likely read it again after I turn it over to my teenage daughter and her older brother. Highly Recommended. Dr. Barbara McNeil teaches in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina in Regina, SK.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- November 29, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |