| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 11. . . .November 15, 2013

|

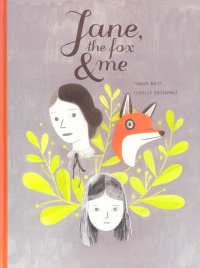

Jane, the Fox & Me.

Fanny Britt. Illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault. Translated by Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou.

Toronto, ON: Groundwood Books/House of Anansi Press, 2013.

104 pp., hardcover & ePub, $19.95 (hc.).

ISBN 978-1-55498-360-5 (hc.), ISBN 978-1-55498-361-3 (ePub).

Subject Heading:

Graphic novels.

Grades 5-11 / Ages 10-16.

Review by Lian Beveridge.

***½ /4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

“Tomorrow I’ll be getting on a bus to Lake Kanawan with forty kids in shorts, not one of them a friend.”

Fanny Britt and Isabelle Arsenault's graphic novel Jane, The Fox and Me is a moving representation of the cruelty of early adolescence. It captures the feelings of helplessness in a period when one’s peers can write “Don’t talk to Helene, she has no friends now” on a bathroom wall, and it becomes the truth (p. 15). Helene has recently been outcast from her group of school friends, and she has taken refuge in Charlotte Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre. At the turning point of the novel, Helene is forced to go on a school camp where she makes friends with a classmate, Geraldine, and a wild fox. After she makes these connections with friends and nature, Helene is able to be happy. The illustrations are evocative and thoughtfully constructed. Nature is quietly represented as a redemptive force throughout the text. Bendy, blobby, wonderful trees creep out through the city skyline and take over full-page spreads by the end of the novel.

The book is pleasurably grounded in a Quebecois setting. I enjoyed the Montreal-specific details – Helene waiting for the bus on Sherbrooke Street, walking up an external winding metal staircase to get to her apartment. Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou’s translation from the French flows well. The slight awkwardness of some phrases make Helene a convincingly idiosyncratic narrator. For instance, she describes “the minuscule laundry room that we call the sewing room because it sounds more promising” (p. 24). Helene’s internal monologue is funny and defiant, although she rarely speaks out loud. When she and her mother are listening to a saleswoman describe a ruffled and belted nautical-themed swim suit, the text says, “I’d like to ask her what sport Monaco Team 51 could possibly participate in just to see the expression on her face, but no sound comes out” (p. 44). The clever language and the surprising beauty of some images keep the book from being melodramatic or overly sad. The book is pleasurably grounded in a Quebecois setting. I enjoyed the Montreal-specific details – Helene waiting for the bus on Sherbrooke Street, walking up an external winding metal staircase to get to her apartment. Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou’s translation from the French flows well. The slight awkwardness of some phrases make Helene a convincingly idiosyncratic narrator. For instance, she describes “the minuscule laundry room that we call the sewing room because it sounds more promising” (p. 24). Helene’s internal monologue is funny and defiant, although she rarely speaks out loud. When she and her mother are listening to a saleswoman describe a ruffled and belted nautical-themed swim suit, the text says, “I’d like to ask her what sport Monaco Team 51 could possibly participate in just to see the expression on her face, but no sound comes out” (p. 44). The clever language and the surprising beauty of some images keep the book from being melodramatic or overly sad.

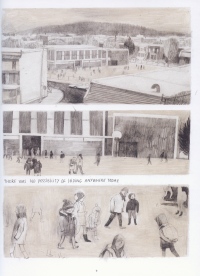

The images capture the isolation and trapped feelings of the narrator. The full-page image of Helene alone and sad in a pool of her own sweat is one of the many times that the images exist independently of words to tell a captivating story (p. 41). Arsenault expresses Helene’s distorted self-image in two images of herself as a human-sized sausage in bathing suits: “In the Monaco suit, I’m a ballerina sausage. In the black suit, I’m an undertaker sausage” (pp. 46-7). The pictures of the Helene-sausage are both funny and terribly sad.

My favourite image in the book is the somewhat surreal picture of Mr. Rochester embracing a large sausage wearing a swimsuit patterned with sailboats (p. 83). Bertha is flailing out the window at them. Although the plot of Jane Eyre is summarised at intervals throughout the text, this image was one of the few times that the stories of Helene and Jane were integrated. The real life pages are black and white and are mainly panelled in a comic style. They have a sketchy unfinished look in parts, which nicely evokes Helene’s emotional state. The pages about Jane Eyre are full-page illustrations, in colour, with cursive rather than block capital lettering. They are mostly watercolour, rather than the scratchy cross-hatching of the real life pages. By the end of the text, Helene’s real life has become full coloured and her words are written in the cursive of Jane’s narrative. While I enjoyed the two distinctive aesthetics in the text, I wish the parallels between the two story arcs had been more carefully drawn out throughout. The fox Helene meets on camp is foreshadowed in the first image of Rochester; I wish there had more nice detail of this sort. I think a stronger editorial hand could have brought to realisation the great possibilities in Jane, the Fox & Me.

I did not enjoy the representation of Helene’s budding eating disorder. The uncritical representation of food as reward for exercise (rather than fuel for exercise) was worrying, and the punch line that Helene isn’t actually overweight is problematic. Lots of people are actually fat, and it doesn’t mean that they “drive off both boys and foxes” (p. 92). I found the story of friendship and the torment of school much more compelling and satisfactory than that of Helene’s unhappy relationship with her body.

Jane, the Fox & Me is a pleasurable and very readable novel. The main character is complex and interesting, the emotional tenor of the narrative plausible and compelling, and the illustrations evocative and pleasurable to look at. It is a text that would bear reading and re-reading slowly in order to enjoy the subtleties of both image and word. I look forward to further collaborations between Britt and Arsenault.

Highly Recommended.

Lian Beveridge is a PhD graduate from the University of British Columbia. Her primary research interests are children’s literature and queer theory.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- November 15, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

The book is pleasurably grounded in a Quebecois setting. I enjoyed the Montreal-specific details – Helene waiting for the bus on Sherbrooke Street, walking up an external winding metal staircase to get to her apartment. Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou’s translation from the French flows well. The slight awkwardness of some phrases make Helene a convincingly idiosyncratic narrator. For instance, she describes “the minuscule laundry room that we call the sewing room because it sounds more promising” (p. 24). Helene’s internal monologue is funny and defiant, although she rarely speaks out loud. When she and her mother are listening to a saleswoman describe a ruffled and belted nautical-themed swim suit, the text says, “I’d like to ask her what sport Monaco Team 51 could possibly participate in just to see the expression on her face, but no sound comes out” (p. 44). The clever language and the surprising beauty of some images keep the book from being melodramatic or overly sad.

The book is pleasurably grounded in a Quebecois setting. I enjoyed the Montreal-specific details – Helene waiting for the bus on Sherbrooke Street, walking up an external winding metal staircase to get to her apartment. Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou’s translation from the French flows well. The slight awkwardness of some phrases make Helene a convincingly idiosyncratic narrator. For instance, she describes “the minuscule laundry room that we call the sewing room because it sounds more promising” (p. 24). Helene’s internal monologue is funny and defiant, although she rarely speaks out loud. When she and her mother are listening to a saleswoman describe a ruffled and belted nautical-themed swim suit, the text says, “I’d like to ask her what sport Monaco Team 51 could possibly participate in just to see the expression on her face, but no sound comes out” (p. 44). The clever language and the surprising beauty of some images keep the book from being melodramatic or overly sad.