| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XX Number 11. . . .November 15, 2013

|

Evangeline for Young Readers.

Hélène Boudreau. Illustrated by Patsy MacKinnon.

Halifax, NS: Nimbus, 2013.

38 pp., pbk., $11.95.

ISBN 978-1-77108-010-1.

Grades 4-7 / Ages 9-12.

Review by Joanie Proske.

** /4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

Long ago, in the land of Acadie, there lived a young woman named Evangeline Bellefontaine. Evangeline was the star in her father’s eyes and was admired by many young men.

Evangeline’s small Acadian village of Grand Pré sat on the shores of the Minas Basin. Villagers grew flax and corn and hay for their animals in vast meadows by the sea.

The children of Grand Pré played in the roads in front of simple houses. Women spun flax, milked cows, and ran the households. The men worked long days, farming the fields. The Acadians lived simply and in peace.

The forced migration of the Acadians from Nova Scotia during 1755 to 1763 is a significant event in Canadian history. It illuminates the British government’s uncompromising policies towards the French inhabitants during the settlement of Canada. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem Evangeline, published in 1847, describes the expulsion of the Acadian people through the lens of a young Acadian woman named Evangeline as she searches for her lost love Gabriel.

As the title suggests, the intent of Evangeline for Young Readers is to retell Longfellow’s best-known work, making it accessible to a younger audience. Nimbus Publishing produces titles relevant to the Atlantic provinces, and Nimbus already offers a French translation of Evangeline, by Sally Ross and Barbara LeBlanc, and so it would appear that this version is intended to reach an English audience.

Historical significance aside, Evangeline for Young Readers does not fulfill its directive due to a number of ambiguities. The book’s cover, dimensions, pastel-coloured text pages, and larger font size initially suggest its intent as a picture book for younger primary audiences. However, the reader soon realizes that the story theme and chapter arrangement are more applicable for intermediate readers. The large font, narrow margins, and lack of paragraph spacing are an awkward combination that affects readability.

Acadian Métis author Hélène Boudreau successfully weaves relevant words and phrases from Longfellow’s original prose into this retelling of Evangeline’s story. Unfamiliar vocabulary, such as notary, flax, bayous, turbulent, tankard, and unusual turns of phrase might offer a challenge to some readers but are well supported through context. The story lacks a compelling narrative voice, perhaps due to the rather stilted use of dialogue between characters. However, despite Boudreau’s best efforts to present a more accessible version of the poem, the underlying juxtaposition is that the story of Evangeline’s tragic lifelong search for Gabriel is unlikely to resonate or capture the interests of younger readers.

The author wisely included factual information about the Acadian expulsion providing necessary historical background for Longfellow’s poem. While his Evangeline poem romantically highlighted the Acadian deportation, controversy exists about the accuracy of its portrayal. Perhaps discussion questions might have been included to explore various viewpoints about the Acadians, especially as this book would best serve as a supplement to school curriculum.

Patsy MacKinnon’s brightly-coloured watercolour illustrations attempt to breathe life into the story of Evangeline by reflecting the emotions of story characters. The full-page watercolour tableaus offer a sense of the historical time period and story events. Unfortunately, much like the story’s text, the illustrations will likely not engage a young audience.

Patsy MacKinnon’s brightly-coloured watercolour illustrations attempt to breathe life into the story of Evangeline by reflecting the emotions of story characters. The full-page watercolour tableaus offer a sense of the historical time period and story events. Unfortunately, much like the story’s text, the illustrations will likely not engage a young audience.

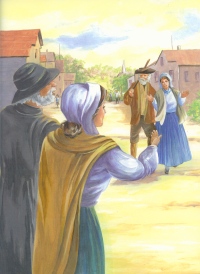

The original black and white inked illustrations of Longfellow’s poems are rich in their intricate detail and beautifully convey the atmosphere of the period. In this picture book, the paintings are bold and colourful but very staid and dated in their composition. Realism has been sacrificed as the artist tries to capture the mood of the poem. Character arrangements are stilted, and unfinished details give the artwork an awkward look. Although bees are mentioned in the text, Chapter Two begins with a small illustration of a wasp nest; the insects painted as undefined yellow oval-shapes without wings or segmented body parts. This primitive approach is also evident in the illustration of Evangeline greeting Basil the blacksmith and his son Gabriel, her beloved. Evangeline’s arms are awkwardly positioned; hands incomplete; the characters’ facial features are crudely depicted, especially in the development of necklines and foreheads.

It would appear that MacKinnon has attempted to replicate the style of the original etchings by leaving the outer edges of her own paintings undefined. In the above scene, the blurring extends into the picture resulting in the visitors being rather disconcertedly cut off at the knees. Compared to the artist’s more current artistic portraiture, such as For the Birds, the style of artwork she has used in this picture book feels dated and is uninviting.

However well intended, this picture book targets a very specific local audience and would not hold wide cross-country appeal. It could be used in a school context as an introduction to Longfellow’s poem or as a supplementary resource to an investigation into the Acadian expulsion.

Recommended with reservations.

Joanie Proske is a teacher librarian in the Langley School District, Langley, BC.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- November 15, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

Patsy MacKinnon’s brightly-coloured watercolour illustrations attempt to breathe life into the story of Evangeline by reflecting the emotions of story characters. The full-page watercolour tableaus offer a sense of the historical time period and story events. Unfortunately, much like the story’s text, the illustrations will likely not engage a young audience.

Patsy MacKinnon’s brightly-coloured watercolour illustrations attempt to breathe life into the story of Evangeline by reflecting the emotions of story characters. The full-page watercolour tableaus offer a sense of the historical time period and story events. Unfortunately, much like the story’s text, the illustrations will likely not engage a young audience.