| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XIX Number 8. . . .October 26, 2012

excerpt:

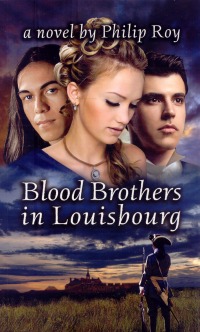

The fortress of Louisbourg, the setting of Philip Roy's novel, was founded in 1713 at a major Atlantic seaport and cod fishing base on present day Cape Breton Island, NS. The fort was barely completed before an expedition of English soldiers and New England settlers captured it in 1745. In the subsequent 1748 peace agreement, it was given back to France. Then, in 1758, the English recaptured it, en route to conquering Quebec. In 1961, Canada's federal government authorized a program to restore fortress and town to the 1740s, and Louisbourg is a popular tourist site today. In this historic setting, Philip Roy tells a coming of age story about two youths searching for father figures and considering what it means to be a man. The novel is presented from two viewpoints in alternating chapters. It begins with Jacques, a 15- year-old French student who is in dismay when his father, a Captain in the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, wants to take him to Louisbourg now that Louis XV has declared war on England. Jacques' father loves warfare and has been away from home for most of Jacques' life. Unlike his father, Jacques likes scientific and philosophical matters. He reads books by the radical philosopher Voltaire, is interested in the new keyboard instrument, the pianoforte, and plays the violoncello. The second chapter is presented in the third person through the heart and mind of Two feathers, a Mi'kmaq youth on a quest to Louisbourg to find his parents. Why are Two feathers's chapters in the third person while Jacques' are in the first person? Possibly the author made this narrative choice to distinguish between two young male voices. Well trained by his community's elders, Two feathers is skilled at living off the land. He is also a deeply spiritual person who hunts only when necessary, communicates telepathically with animals, and feels in tune with the spirit world. On his way to Louisbourg, he is led by a doe to a great oak with birds singing in its branches and the snow melting around its trunk. "Two feathers was in awe. It was as if he had discovered the very origins of spring." Two feathers' mother had left their Mi'kmaq community for Louisbourg earlier in the season in the hope that her lover would come back from France. "After two seasons he [had] returned to his own land and she to her people... where she gave birth to Two feathers, so named because the blood of two people ran through his veins." In a cavity in the tree trunk, Two-feathers finds her bones, identifiable by the cameo pendant his father had given her. While conducting her funeral ritual, Two feathers feels sad but sees the tree as a "fitting resting place for his mother." The political situation is presented in conversation between Jacques and Monsieur Anglaise, a rich merchant staying with the governor. M. Anglaise has arranged for Jacques to give violoncello lessons to his 16-year-old daughter, Celestine. "We're here ... mostly for the fish... for the money," he tells Jacques. "Beneath the surface of political intention you will always discover the deeper cold current of commerce." The English colonists along the Atlantic seaboard are a formidable enemy because they are fully committed to life in the New World and perceive Louisbourg as a threat. "Between you and me, Jacques," he says, "I worry that we may be a sitting duck." In 1754, ten years after the novel takes place, the philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) wrote in Discourse on Inequality: "The fruits of the earth belong to us all and the earth itself to nobody." Roy's novel conveys the feeling that the European project of conquest and colonization is bad not only for the conquered, but also for the conquerors. Jacques sees no glory in killing or being killed. He learns that many enlisted men at Louisbourg had been forced into the army as an alternative to imprisonment on trumped up charges of theft. On an expedition to conquer the English fort, Annapolis Royal, Jacques is shocked at the lies his father tells the Acadian settlers to try to persuade them to join the war party. Two feathers, convinced that he will find and recognize his father among the "blue coats", begins sneaking into the fortress at night. One morning, hiding in a sheep pen, he sees the lovely Celestine getting water. He thinks of her as "the rainbow girl" and loves her from afar. When she eventually notices him, she is fascinated, not frightened. Later, she asks the priest if Natives have souls. Throughout the hungry winter, Two feathers brings her gifts of cooked rabbit and other game when he sneaks into the fortress. On these nocturnal adventures, Two feathers discovers some hungry children, offspring of French soldiers and Native mothers, with no one looking after them. In the long run, Two feathers' sense of duty to these Metis children is stronger than his attraction to Celestine. Ultimately, he takes on a parental role, providing for the children and also telling them that he, and they, are metis, "something new." Meanwhile, on night watch, Jacques glimpses the intrepid Native running around the fortress. Jacques is so fascinated by the other man's agility and daring that he never alerts his comrades. Tension builds during a brief encounter between Jacques and Two feathers, and ultimately, with the danger of an English attack. Although this novel is a boys' story, centring on the two male co protagonists' coming of age process, girls will be enticed by the attractive cover design and the romantic triangle created by the attraction both young men feel for Celestine. Readers of both genders who like to solve puzzles and feel smart will enjoy the hints that Two feathers' deserting "blue coat" father is Jacques' war loving father. Other than one brief encounter, the young men never meet, and neither is aware of their blood connection, though Jacques wonders how Celestine happens to have the turquoise cameo pendant that his mother had given his father on his first trip to Louisbourg. Evocative detail, lyrical language and good pacing make this novel a winner. There are a couple of small problematic details, however, along with a larger question. Since the French and the English (les Anglais) are at war, why call a character "Mr. Anglaise"? Since he is a rich merchant, couldn't he be called "Mr. Bourgeois"? Also, "Two feathers" is a fluffy, lightweight name for so dramatic and heroic a character. Throughout the novel, Two feathers is presented as being more courageous, self possessed and spiritual than any European. Clearly he is what Monsieur Anglaise would call a "noble savage". (see p. 20) This term, undefined in the novel, was used in a positive sense by its 17th and 18th century originators who believed that human beings in a state of nature were better in most ways than those who had been spoiled by civilization. The term is often associated with Jean Jacques Rousseau, but at the time the novel takes place, he had not yet published his major works on human beings in society. In 1699, however, the Earl of Shaftesbury used the term "noble savage" in an essay taking issue with Thomas Hobbes' assertion that, in nature, human life was "nasty, brutal and short." Eighteenth century Europeans were fascinated by tales of sea voyages to faraway places inhabited by people living free in Edenic surroundings, and in many writings of that era, native people are romanticized. It seemed to me that Roy romanticized Two feathers by making him so heroic. However, I do not doubt that the skills and inner resources demonstrated by Two feathers came from Roy's research into Mi'kmaq culture and his wish to represent it authentically. Highly Recommended. An Ottawa, ON, resident, Ruth Latta says her latest novel is The Old Love and the New Love (Ottawa, Baico, 2012, baico@bellnet.ca)

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- October 26, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |