| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XIX Number 37. . . .May 24, 2013

excerpt:

The title of Janet Wilson’s informational picture book and the anecdote of the Star Thrower cited above announce two of its major premises: (1) all children have rights and (2) many children are exercising such rights to change the world for the better. Wilson’s rights and activists-based text suggests that making a meaningful and positive difference in local communities and beyond is important to the globe’s children. Driving home the messages of this thoughtfully illustrated and photograph-rich work are biographies about diverse children from around the world who actualize human rights and initiate and carry out social justice-oriented change in their lives and those of others.

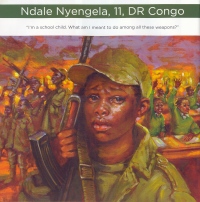

A recurring organizational pattern is used for each biographee. The author employs a double-page spread with a successful balance of exposition and narration to provide information about each biographical subject. The subject’s full name, age and country of residence are printed and centered boldly across the top of the left page. This is followed by a quotation from the child, and beneath that is Wilson’s unique illustration of him/her. The illustrations are detailed and iconical and sensitively capture the emotions and feeling of each child’s particular context through the use of strong lines and intense colours. The right side of the double-page spread has two text boxes: a photograph of the child, a fair-sized paragraph that informs readers about his/her human rights and activist work while the other text box comprises a quote and combines relevant words and photographs to showcase and elaborate issues important to the biographical subject. This organizational structure makes it easy for students to navigate their way through the book and provides just enough content to give readers an initial understanding about the biographee’s activism. Many children will appreciate hearing the compassionate and fairness-minded voices of their peers as the activists detail the motivations for their activism, and, in this way, readers experience the mentoring work of the book. Also, the textual load of the biographies is especially considerate of the needs of readers between grades 3-8. It will not overwhelm them and is likely to encourage interested readers to return to the book time and time again. The high interest value and accessibility of the book make it a solid choice for reading aloud to students. As concerns the entries, the 10 principal biographies spotlight the social activism of five girls and five boys. As well as respecting the principles of gender fairness among the main biographees, Wilson exhibits sensitivity with regard to the geo-political origins and social locations of the subjects. As a result, six of the principal biographees are from emerging nations and only four from developed countries. Of the four, the two from Canada are female and non-white. In this way, the author succeeds in being socially inclusive whilst illustrating that the role of activism, of acting as an agent for positive social change, is available to all children—especially those from minoritized and marginalized groups. It is interesting to note that, while caring and moral work of one of the featured Canadian activists (Shannen Koostachin) was focussed on fighting for the right to a quality education in Canada, the other was concerned with preventing the “commercial exploitation of children and providing homes and counselling for survivors.” The inclusion of these examples gives the book a local as well as global perspective and informs children that there is work to be done at home and abroad, thereby encouraging them to look in and to look out. Thus, this is a book that casts light on the moral reasoning and work of the children. The author deserves credit for making readers aware that we live in a world where parents, guardians, families and communities contribute to raising children to think and act in ethical ways. A good example of the compelling and clearly-written entries Wilson provides is the one about Shannen Koostachin. She was a member of the Cree Nation from the Attawapiskat reserve in Ontario who refused to keep quiet about inequitable schooling in her community. At the age of 13 (2008), Shannen travelled to Parliament Hill. There, she courageously used her voice to tell the nation about the harsh material conditions she experienced as she sought to get an elementary education (cold classrooms, limited learning resources, sub-standard school) that is commonplace to many Canadian children and youth. Two years later, Shannen died in a car accident. With such a heart-wrenching, tragic situation, Wilson, as illustrator and writer, needed to create a befitting entry that would honour Shannen visually and textually. She does so. Wilson’s illustration of Shannen shows a bold, quietly pensive and empowered young woman whose face catches and resonates the radiating light emitted by the medicine wheel that is positioned just behind her right shoulder. Painted in red, black, white and yellow according to Cree tradition, the medicine wheel is symbolically representative of Shannen’s core values, individuality, indigeneity and connection to the wider world. Complementing this is a quote from Shannen and facts about inequities Indigenous children experience in Canada. Our Rights: How Kids Are Changing the World is worthy of space in school and public libraries. This collection of short, factual biographies is well-written and documents the activism of children from far and near (e.g., South Korea, Philippines, Yemen, and the United States). It concretely demonstrates that children are making, and can make, positive changes in their worlds while fighting for and actualizing their rights. Thus, the book is inspirational as well as aspirational for young people-- especially those in grades 3-8. A practical and rewarding feature of the book is the information that follows the biographies. Here, readers learn about kids who “take action”, “create” and “what youth can do.” This is a fitting conclusion to a book about child activists because it scripts and illuminates concrete actions that kids can take to participate in the construction of the worlds they wish to see and experience. After examining this book, I was eager to learn about the process the author used to assemble the information and admit to being disappointed that there is no evidence to show that she has met or spoken with any of the biographees. However, located at the back of the book is explicit information about the sources for the information about the biographical subjects—the organizations concerned with promoting and celebrating the work of young activists and reformers. Included as well, is a compilation of sources of additional information, such as the website where readers can find the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and web links to some of the featured activists. In view of the subject matter and the intended audience, the absence of a table of contents, pagination, an index, and a reading list detracts from this otherwise useful informational work that introduces and informs children about their rights, active citizenship, social responsibility for self and other, and possibilities for positive social change. Above all, Our Rights: How Kids Are Changing the World is valuable because it explicitly educates and encourages children and youth to know their rights and work alongside others to co-create and re-create the world. It is written by someone who values children and is inspired by their challenges to the status quo. Recommended. Barbara McNeil is an instructor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Regina in Regina, SK.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 24, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

The book begins by highlighting each article of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), thereby immediately alerting and informing readers of the fundamental rights of all children. With that as its central platform, this timely work of collective biographies highlights the courageous and significant contributions of 10 human rights and social reform-minded children under the age of 16. They include children from places such as Brazil, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo and India.

The book begins by highlighting each article of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), thereby immediately alerting and informing readers of the fundamental rights of all children. With that as its central platform, this timely work of collective biographies highlights the courageous and significant contributions of 10 human rights and social reform-minded children under the age of 16. They include children from places such as Brazil, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo and India.