| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XIX Number 27. . . .March 15, 2013

excerpt:

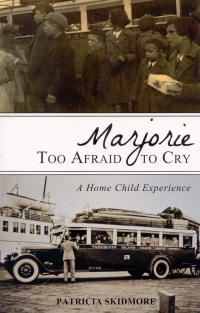

Marjorie Too Afraid to Cry, is the third book from Dundurn Press about child immigrants to Canada. Between 1833 and 1948, British philanthropic societies and the Church of England moved thousands of poor children to Canada and other British colonies/dominions. "Barnardo" children were sponsored by Dr. Thomas Barnardo's well-known homes. The Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School Society, which sent Marjorie Arnison to Canada, was sponsored by the royal prince who later became the Duke of Windsor. As Patricia Skidmore points out in Marjorie Too Afraid to Cry, the children provided "white stock" and cheap labour for the countries receiving them, while decreasing the number of people "on the dole" in Britain. Not all of these children were orphans. Many, like Skidmore's mother, Marjorie Arnison, had parents who were persuaded that their children would have a better life in Canada. For many, including Marjorie, being shipped overseas meant loss, "loss of country, loss of records, loss of family and roots." Skidmore's book is unique in several ways. First, the central figure in her story, her mother, Marjorie, is still alive and was able to travel to London in 2010 to meet British (Labor) Prime Minister Gordon Brown when he formally apologized to all child migrants for their exportation. Other books, centring on Victorian "home children", cannot provide the closure that Skidmore's book can, nor her "then and now" photographs showing Marjorie both as a frightened child and as a good-looking senior citizen. Skidmore's book stands out, as well, for her solid research and documentation along with her fictionalized account of Marjorie's five years under the guardianship of the Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School Society. There are 127 pages of factual information and documentation (including the text of Prime Minister Gordon Brown's 2010 apology to the child emigrants) and 158 pages of historical novella. When an author is presenting a tragic historical event, especially one which stirs debate as to the scale and level of tragedy, it may be best to write it as nonfiction and back up your assertions by citing sources. On the other hand, fiction can bring a story to life and touch the heart in a way that non-fiction often fails to do. Skidmore, very sensibly, does both. Marjorie Too Afraid to Cry is also unique for its focus on the harm done by the uprooting of Marjorie and her siblings, rather than on their sufferings in Canada. One cannot deny that many "home children" were exploited in Canada, but for many, like Skidmore's mother, it was the trauma of being ripped from their families that blighted their lives and those of their own offspring. As a girl, Pat felt rootless because of her mother's reluctance to talk about her past. Judging from what Skidmore tells readers, there was nothing much wrong with the Arnison family except that, for reasons beyond their control, they were poor at a time when the world economy was in chaos and the social welfare system was rudimentary. Until age 10, Marjorie and her family lived in seaside Whiteley, near Newcastle upon Tyne. During the Great Depression, her father, like many other Tyneside workers, left home to find work elsewhere. Marjorie's two teenaged brothers committed petty thefts and were sent away to reform school; Mrs. Arnison had trouble finding housing, and the town council reported to the children's school that the father had deserted the family. Thus the question of a children's "home" and possible emigration arose. Skidmore reproduces a letter from Marjorie's father to the Fairbridge Society:

While this letter shows the predicament of a struggling worker who hopes to move his family near him, an official in the Fairbridge Society interpreted it otherwise, writing, "This is a consent" across this letter, and with that, four of the Arnison children, including Marjorie, were whisked away against their mother's wishes. (Skidmore reproduces this letter in her book.) Since Marjorie had not seen her father for three years, it was her mother she blamed for giving her up. At first, she believed she was going to jail like her elder brothers. Four of the Arnison children were taken to a Fairbridge home near Birmingham, and Marjorie and her brother Kenneth were sent overseas to the Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School near Cowichan Station on Vancouver Island. Their sister Audrey was sent later while Joyce, the older sister, was left behind. In 1986, Pat Skidmore visited the Fairbridge Farm School grounds.

In 1942, at age 16, Marjorie was placed as a domestic servant in British Columbia. (Girls from the Fairbridge School became domestic servants; boys, farmhands.) At 22, in 1948, she married the love of her life, Clifford Scott Skidmore, who was in the Merchant Navy and stationed in Esquimault. When Cliff died at 32, leaving Marjorie five children ranging in age from infancy to eight years, she had to go on provincial welfare. When a social worker suggested that she give up some of her children, she refused and fought to keep her family together. "It has taken a couple of generations, a formal apology and a strong reconnection with our English family to finally feel that we have a place of belonging, a sense of family pride, and a sense of family history," writes Skidmore. When Marjorie eventually contacted her siblings in England, she learned that their mother had never got over losing three of her children to Canada. In February 2010, in London to take part in the official apology ceremony, Pat noticed that Marjorie "shed any vestiges of shame and walked with her head held high" after hearing Prime Minister Brown's words. The Family Restoration Fund, part of the Child Migrants' Trust, later enabled Marjorie to meet her youngest brother, stationed in Cyprus, who was born after she left England. The best part of the 2010 trip, to Marjorie, was getting together with her English siblings. "A bad home is better than a good institution," wrote British psychiatrist Sir Alfred Forrie, commenting on the World War II evacuation of London children away from their parents to safer locations. Skidmore agrees with Forrie to a point, but she takes his thought further. She points out that do-gooders of the past believed that the only way to make decent citizens of impoverished children was to remove them from their families' influence. Many "home children", who were told repeatedly that they were bad and that if they'd stayed in England they would have ended up in jail, had their spirits broken. Marjorie Too Afraid to Cry will make readers want to cry. After drying their tears, they may think about other questionable social engineering experiments (like the residential schools for native people) and about the big holes in our present-day social safety net. Let's hope that Skidmore's excellent book completes the restoration of Marjorie Arnison's spirit. Highly Recommended. Ruth Latta's most recent book, one for teens, is The Songcatcher and Me (Ottawa, Baico, 2013, (baico@bellnet.ca).

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- March 15, 2013.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |