| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVIII Number 41. . . .June 22, 2012

excerpt:

Tecumseh is another of the books about the War of 1812 being released to coincide with the 200th anniversary commemorations. This book focuses on the life and accomplishments of the best known Native American leader during the War of 1812, Tecumseh.

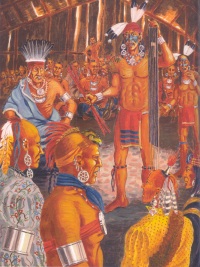

Laxer’s text, although written for junior age students, still manages to evoke a sense of the magnitude of Tecumseh’s accomplishment. At a time when there was no CNN or social media, Tecumseh’s skills as an orator and a warrior earned him the respect and trust of people who had previously lived and functioned as autonomous tribes. His insightful recognition of the vulnerability of individual tribes led Tecumseh to dedicate his life, and to eventually lose his life, fighting for justice for Native Americans. Richard Rudnicki’s illustrations are both a strength and a weakness of this book. Rudnicki’s well researched pictures portray rich details of the time period. He depicts the plants and animals, homes and buildings that make up the background of the pictures, as well as details of the apparel of the native people and the soldiers and administrators. Not surprisingly, given that this is a book about a war leader, the illustrations depict a lot of violence. The weakness of the illustrations is their failure to effectively depict the non-violent aspect of Tecumseh’s leadership. For example, there is something unsettling, even slightly sinister, in the portrayal of Tecumseh’s meeting with General Brock. Tecumseh begins with an explanation of the primary sources of information about Tecumseh’s life.

Included in the “For Further Reading” resources is a link to a digital copy of Stephen Ruddell’s Reminiscences of Tecumseh’s Youth in Ruddell’s own handwriting. This provides an excellent opportunity to teach the distinction between primary source material and other resources. Tecumseh also includes a “Table of Contents”, “Events in the Life of Tecumseh”, a glossary, a detailed list of sources, a map of the original Thirteen Colonies, 1733, a map of European claims to North American lands, 1800-1809, and a map of the lands defended by Tecumseh’s confederacy, 1810-1813. Tecumseh ends with an epilogue which summarizes events following Tecumseh’s death on October 5, 1813 in the Battle of Moraviantown near London, Ontario. The Treaty of Ghent, signed by the United States and Britain, resulted in no territory changing hands.

Inexplicably, the final sentence in the book describes Tecumseh as “a symbol of justice for the native tribes of North American.” A symbol of the struggle for justice would be more accurate and more fitting. Although the text of Tecumseh portrays the man as a visionary leader, the illustrations focus on the violence of the times. Your money would not be poorly spent if you choose this book, but you may want to see what else is available before you settle for this book. Recommended. Suzanne Pierson, a retired teacher-librarian, is currently instructing Librarianship courses at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- June 22, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

Author James Laxer presents a well researched, informative depiction of the man who formed and led a confederacy of tribes against the westward expansion of European settlement.

Author James Laxer presents a well researched, informative depiction of the man who formed and led a confederacy of tribes against the westward expansion of European settlement.