| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XVIII Number 30 . . . . April 6, 2012

excerpt:

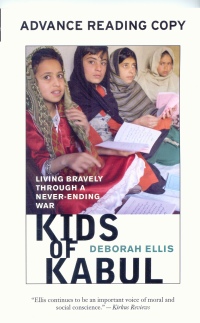

With a history of philanthropy and activism, Deborah Ellis is an acclaimed author of several award-winning works for children and young adults, including her well-known "Breadwinner" trilogy. Besides her fiction, she has published nonfiction works about people who have experienced hardship due to war, poverty, or illness, books such as Our Stories, Our Songs: African Children Talk about AIDS (2005) and Children of War (2009). Ellis' interest in Afghanistan is reflected in her writing of the "Breadwinner" trilogy as well as nonfiction works such as Women of the Afghan War (2000) and Three Wishes: Palestinian and Israeli Children Speak (2004). Through these works, Ellis contributes to our understanding of these situations and, at the same time, she validates the people's experiences by giving them a voice. Deborah Ellis's Kids of Kabul contributes further to this body of work by exploring the contemporary lives of people in Kabul through interviews that she conducted with Afghan children and teens. She discloses the hardships that they, their families, and communities have experienced as a result of Afghanistan's long history of war and occupation by foreign powers. Consequently, readers get an intimate and personal look at Afghanistan's situation from the perspective of young people by letting them speak for themselves. At the same time, sufficient historical context enriches the readers' understanding of the situation in Afghanistan. The book is organized as a series of interviews that Ellis conducted in 2011 when she was in Kabul, Afghanistan. Besides an accompanying photo of the young person, each interview is also prefaced with Afghanistan's cultural, political, economic, or social climate, which will help readers to understand the interview's significance and the broader societal context that affects these young peoples' lives. Ranging in age from 10 to 17, these young people's stories give readers a vivid window into people's daily lives in Afghanistan. Although the mainstream news sources do cover Afghanistan, the events are framed by the reporters' or broadcasters' viewpoint, without significant inclusion of perspectives from the people who actually live there. Ellis's Kids of Kabul provides such an approach as it goes beyond the "factual" reporting in the news and provides a more intimate understanding of Afghanistan from the perspective of young people. In doing so, the book validates their experiences and reveals the complexity of life in Afghanistan. All the young people express a desire for a better future for Afghanistan, their families, and themselves, but they also recognize that such a process does not come about quickly. Several of them acknowledge the difficult conditions that may hinder them, such as their impoverished circumstances, lack of education, and unstable family situations. For example, Mustala's family has been split apart by war while Karima must deal with an abusive domestic situation. Other young people's difficulties arise from their economic circumstances which are compounded if they are women. Palwasha affirms that the Taliban were hostile towards women's rights and that, even though they are no longer in power, it is still difficult to be a woman in Afghanistan because of close-minded people with certain views of what behaviours and jobs are appropriate for women. As Liza asserts, it is challenging to live without a man in the family because of restrictions on women's opportunities for making a living and improving their families' circumstances. These restrictions extend to the harsh treatment of women under the country's legal system. One anonymous interviewee was involved in an arranged marriage at a very young age, a marriage which caused her to sacrifice her educational and career aspirations. When she was caught for running away from her husband, she was sentenced to prison for seven-and-a-half years. As seen in these interviews, poverty-related illnesses, poor health conditions, and poor health care have also resulted from the war and instability in Afghanistan. The psychological despair that some people experience due to war may consequently drive them towards self-destructive behaviours that, in turn, adversely affect their family's lives. For example, Sharifa recounts how her father is addicted to opium because it helps him to forget his memories of the war. However, as the book illustrates, organizations are helping people to rebuild their lives. The Afghan Landmine Survivors' Organization (ALSO) has helped people who have become disabled due to land mines, while SOLA [see Note] has helped war-torn countries such as Afghanistan. Women's shelters have also arisen to help Afghan women who need to escape their homes due to domestic violence or other reasons. Besides the negative ramifications of poverty, Afghan citizens have become displaced internally as well as externally. Ellis's prefatory material to Shazad's interview states that there are over two million refugees in Pakistan and Iran and over 450,000 Internally Displaced Persons in Afghanistan. Other circumstances also affect their long-term mobility, such as mental illness, disability, and imprisonment. A recurring theme in this book is that for the rebuilding process in Afghanistan to occur successfully, it must occur at the grassroots level rather than simply from the level of government and must involve both the younger and older generations of people. As part of this process, people are reclaiming and transforming formerly hostile space into an empowering space for the community. For example, a room in a Taliban member's house has been converted into a meeting room for teaching literacy classes to women. Similarly, a soccer stadium previously used as a torture chamber is now used for the Afghan Women's National Football Team's offices and football practice. However, rebuilding also involves more than the physical reconstruction of their communities that have been torn apart by war. As suggested in the book, it involves also the societal regeneration of communities in all facets of life: education, health, sports, and the economy. Central to this regeneration is the young generation, a position which is affirmed with cautious optimism by several of the young interviewees. One key aspiration expressed by them is that they would like to help to rebuild their communities, revitalize Afghanistan as a whole, and, in doing so, contribute to the well-being of their families. They aspire to various occupations, such as being a teacher, a lawyer, an artist, an ambassador, or even president of Afghanistan. Although Ellis's interviews are with people who are outside the realm of many North Americans' daily experiences, readers will be engaged with the book because they will be able to identify with the interviewees. Although their circumstances have caused them to grow up more quickly by necessity, they also have feelings and aspirations that are similar to other young people their age, regardless of nationality or cultural background. Like children in North America, the Afghan children want to enjoy their current lives. They want to experience life as kids and have fun with their friends, even if such opportunities are limited by their need to survive economically. Many interviewees express a desire to do well in school and complete their education, recognizing that this will enable them to take advantage of future opportunities for improving their communities, family's circumstances, and personal lives. This involves people working within their communities in their own ways, whether it is through teaching, assisting with organizations, rebuilding civic institutions such as the local museum, or other means. At the same time, other young interviewees regard the future with some trepidation, particularly some of the young girls who continue to feel constrained by gender expectations in their daily lives. The language of the book is appropriate for its readers of age 12 and up. The book also includes a glossary of unfamiliar terms, a map to indicate where Afghanistan is located, and an introduction in which Ellis situates herself in relation to her book. This will help readers who may be unfamiliar with some of the vocabulary used or with the location of Kabul in Afghanistan. At the end of Kids of Kabul, Ellis has a list of organizations and books that readers can consult if they would like to learn more about Afghanistan's situation. If the book has sufficiently sparked readers' interest, they may also wish to get involved in some capacity with the organizations. In her introduction, Ellis is optimistic that post-war Afghanistan's conditions will improve with time, but that it will require a concerted, sustained effort from its citizens as well as organizations and other individuals who are dedicated to the rebuilding process. Kids of Kabul would be a good addition to school and public libraries because its coverage of post-Taliban Afghanistan offers a unique perspective that is often unrepresented in the mainstream news and literature. Although the news does report on Afghanistan and works of fiction have also been written about it, few works focus on the actual experiences of young people who live in that country. Kids of Kabul is, therefore, timely because it offers a current view of Afghanistan from the individuals who will be affected by it most in the coming years: the young people who are growing up in that environment and who signify the tipping point between a past full of turmoil and violence and a future that is potentially more optimistic. As part of a teaching unit, Kids of Kabul can be used in a discussion regarding the immediate and long-term consequences of war and violence on people's communities and how, in turn, these consequences will affect people's daily lives in the most basic ways. Alternatively, the book can be part of a specific history or social studies unit about the Middle Eastern history and society. Even as part of a media studies unit, a discussion can be started about the extent to which the book may challenge the forms of media representation regarding Afghanistan and other countries in the Middle East. To facilitate the learning process of students and increase their engagement and interest in the book, teachers can provide background information about Afghanistan. As a work of literature, this book can be incorporated into an English unit about the representational strategies or representations of traumatic experiences in literature and non-fiction. For more information on Deborah Ellis, see her CM profile at http://www.umanitoba.ca/cm/profiles/ellis.html and her profile from her publisher's website, http://www.houseofanansi.com. Highly Recommended. Huai-Yang Lim has completed a degree in Library and Information Studies and currently works as a research specialist in Edmonton, AB. He enjoys reading, reviewing, and writing children's literature in his spare time. Note: According to the text, "SOLA is an organization that tries to repair some of the damage that war and the resulting poverty have caused. It arranges rehabilitative surgery in the United States for kids like Shyah, who are given a home and an education so that when their bodies are repaired, they are better equipped to make something of their lives."

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- April 6, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |