| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XVIII Number 27 . . . . March 16, 2012

|

Sugar Falls: A Residential School Story.

David Alexander Robertson. Illustrated by Scott B. Henderson.

Winnipeg, MB: Highwater Press/Portage & Main Press, 2011.

40 pp., stapled, $15.00.

ISBN 978-1-55379-334-2.

Subject Heading:

Native peoples-Canada-Residential schools-Comic books, strips, etc.

Grades 10 and up / Ages 15 and up.

Review by Joanne Peters.

*** /4

|

| |

|

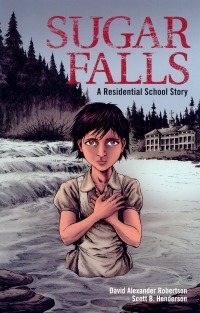

A young girl, dressed in a drab dress and pinafore, stands in the middle of a pool of water staring forward impassively, hands crossed on her chest. To one side of her is a cascade of water known as Sugar Falls. On the other side is a stretch of still water, behind which looms a two-story building, its roof surmounted by a cross-crowned cupola. It is a residential school run by the Roman Catholic Church. This scene is the front cover of David Alexander Robertson’s 40-page graphic novel, Sugar Falls. Although written as a work of fiction, it is based on the true story of Betty Ross, an elder from Manitoba’s Cross Lake First Nation.

Having just finished an essay about Helen Betty Osborne (whose story was recounted in Robertson’s The Life of Helen Betty Osborne), a high school student named Dan finds himself faced with yet another assignment. This time, he must consider aspects of the residential school system: “How does it affect the First Nations people and why does it affect them today? How does understanding the system change your view of First Nations People? Should it? [His] assignment is to consider these questions. . . .” However, the assignment also requires that Dan “seek out a personal account from a residential school survivor” and then tell that individual’s story. Although Dan doesn’t know anyone he can interview, fortunately for him, a classmate, April, happens to have a grandmother who is a survivor of the residential school system. April has always wondered about her grandmother’s school experience and so, after a quick phone call to her Kokum (her grandmother), the two young people hop on a Winnipeg transit bus to meet with her and to undertake the assignment. (Although the author does not directly name the city in which the story opens, the drawings feature a number of landmarks familiar to Winnipeg residents.)

Kokum has never before told the story of life at residential school to anyone, including her granddaughter. Attired in traditional garb, sitting in a round room on a star blanket, holding an eagle feather, and amidst the smoke that wafts from the burning of sacred medicines, Kokum begins her story after Dan asks her why she attended the school.

It is a sad story: abandoned at age five by her mother (herself a residential school survivor), Betsy wanders in the bush in a bitterly cold winter. A trapper finds her under a canoe near a lake, takes her to his home, and, until she turns eight, Betsy enjoys the warmth of a loving family. One evening, her foster father shares with her a disturbing vision, “a vision of darkness that comes in your future.” The only protection he can provide her is to take her to Sugar Falls where he reminds Betsy to find strength in the relationships “between our ancestors, our traditions with mother earth, and with each other. Knowing this will keep you strong.”

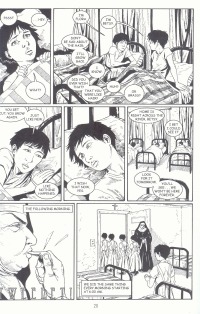

The darkness arrives in the form of the priest who takes Betsy to the residential school and gives her into the charge of Sister Marie, a martinet nun who scours her in the bath, cuts her hair, and initiates her into a daily regimen of prayer, substandard food, hard labour, and complete annihilation of personal identity. In her classroom, Sister Marie terrorizes students with disdain and with a ruler which is regularly smacked against the hands of girls whose transcription of Latin scripture fails to meet her standards for perfect penmanship. The days are unremittingly difficult; at night, Betsy remembers her home, and she stands at the windows of her dormitory, thinking about her parents and wishing she were with them. And at night, there is even more darkness: each of the girls in her dormitory is victimized, in turn, by the sexually abusive priest (he is never named in the book) who runs the school. Corporal punishment, sexual molestation, and denial of the right to speak their language – all this was endured by the students. “The way we talked, the way we looked – there was to be no more Indian by the time they were through with us.”

Finally, Betsy’s friend, Flora, decides to escape, and, together with another girl, they wade into the river and attempt to swim across; however, Flora perishes in the attempt. Undeterred, Betsy makes another attempt to leave the school; unsuccessful again, she remembers her father’s words and decides that she will succeed, but on her own terms. At the end of her story, Dan asks Betsy about the school friends that she lost, including Flora. One of those lost girls was Helen Betty Osborne, who lived in Norway House, downstream from Sugar Falls. Devastated by her friend’s murder, Betsy changes her name to Betty, to honour her friend’s life and keep her memory alive. Dan is honoured that Betsy/Betty shares this formerly untold story with him, and so the story ends with the hope that, by telling of stories from the past, the future will bring healing.

As an account of the residential school experience, Sugar Falls presents a sad and difficult story. Scott Henderson’s black and white drawings underscore the bleakness of residential school life, and Betty’s story reiterates the inter-generational impact of that experience on First Nations families. Unlike David Robertson’s “7 Generations” series, in which storylines shift between past and present, this narrative is straightforward, direct and accessible to high school readers of various reading abilities. However, there is much in the book’s content that is disturbing - particularly the depictions of corporal punishment and description of sexual abuse – making this a book unsuitable for audiences under the age of 15.

Sugar Falls can be used in a variety of senior high school instructional contexts: in language arts/English classes studying literature of the Aboriginal/First Nations experience, as a supplemental text in social studies classes, and in Aboriginal/First Nations studies courses. As well, it is worth acquiring for a high school library’s graphic novel collections. However, due to the book’s content, potential purchasers should read the book carefully prior to acquisition and consider possible challenges within its school community. As well, teachers and teacher-librarians working in Catholic education contexts or in public schools with large Catholic populations are cautioned that the nun and priest of this story present a shameful example of the Catholic church’s role in the history of residential schools. Use of this book in a Catholic school context necessitates careful consideration of how to offer balance, fairness, and sensitivity in the telling of this story.

Recommended.

Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- March 16, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |