| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XVIII Number 23 . . . . February 17, 2012

|

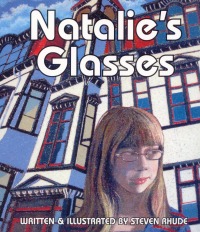

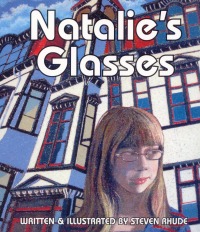

Natalie’s Glasses.

Steven Rhude.

Lunenburg, NS: MacIntyre Purcell Publishing, 2011.

52 pp., pbk., $19.95.

ISBN 978-1-926916-16-3.

Grades: 4-7 / Ages 9-12

Review by Keith McPherson.

**1/2 /4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

“I am here to day to deliver some very important news,” continued the superintendent, “next year, your dark, creaky, out-of-date, old, decrepit, in-need-of-paint…” She caught herself and continued again, “…in-need-of-paint school will be closed. You will now have a chance to attend a new school…a modern school. A school of the future!”

Nine-year-old Natalie is one of many children attending the Lunenburg Academy who listen to a Nova Scotia school district superintendent’s decree that their beloved 116-year-old heritage ‘palace school’ is to be closed. Not ready to blindly accept the superintendent’s decision, one of Natalie’s friends, Ezra (whose name means helper) asks the superintendent the question on every child’s mind, ”…why do we need a new school? This one is already built?” The superintendent’s response is that a new school is required because enrollment is down, the school is “old and creaky” and full of “needless details”. The children, however, don’t see it this way, setting the crisis around which readers begin to understand the significant impact that modernization can have on children.

Because the book is written in the first point of view, readers come to know Natalie’s deep insights and reactions to the closure of her beloved school. This perspective is particularly effective in that it clearly conveys Natalie’s thoughts, feelings, and struggles as she asks herself questions and tries to synthesize adults’ actions and reactions around the impending closure of her school. It is through these insights that readers not only feel like they are reliving the life and struggles of a nine-year-old, but readers also come to know the deep impact that adults decisions can have on youth and that children’s concerns and problem solving skills can be much more sophisticated and, sometimes, well informed than adults may assume.

The Flesh-Kincaid readability level of this 52 page chapter book falls around a grade 4.2 level, making it perfect for the average Grade 4 reader. My nine-year-old had no difficulty reading this book on his own over a four day period. Additionally, the text is accented with full-page paintings (aside from a few partial page images near the end of the story) which not only give the book a picture book feel, but also help to reduce the intimidation factor readers may experience when faced with reading eight chapters of uninterrupted text.

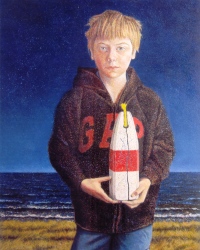

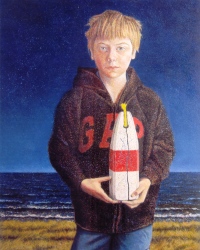

The images, themselves, are a mixture of paintings and drawings. Paintings are done in a pointillism style, yet often convey a crisp reality. Drawings are done using materials such as pencil and charcoal and have a soft, almost smudged, unclear/unreal look and feel about them. The images correspond closely to the story and add a great deal of information not conveyed through the text. For example, moments in the story when Natalie is being taken seriously by adults, and/or instances when Natalie’s thoughts rest upon a very sobering topic, the images are drawn in soft black and white smudged lines conveying a very solemn, unclear, and almost sobering tone. The many colourful painted images have a very real, clear and colourful feel about them and often capture and reinforce the beauty of the real world that Natalie sees about herself.

Additionally, Rhude does a fine job of conveying a child’s perspective of the world through his images. For example, children will likely have no difficulty at all relating to the huge in-your-face, fill-up-your-whole-vision painting of the superintendent’s face as her wrinkly and intimidating features reinforce Natalie’s written perspective that adults don’t really understand grade four children and that adults “like being the boss of you”.

Images and text also convey a very strong sense of an east coast Canadian community. Children who do not live on the east coast of Canada will be treated with images of dories, wooden buoys, scenery, clothing and other images indicative of an east coast Canadian community. Children who live on the east coast will have no trouble identifying with Rhude’s authentic portrayal of key attributes of his and their communities. Additionally, Natalie’s experience with her grandad on the water will leave children with an appreciation of the skills and dangers that Nova Scotian fishing communities require and face on a daily basis when making a living off the ocean. Rhune does a very solid job of using both image and text to have his readers see this Canadian community through Natalie’s eyes, and to temporarily identify with, and become part of, this vibrant community.

Although the story is short in length (it almost feels like it ends too soon – I wanted to see the results of Natalie and her classmate’s actions), it is definitely ‘long’ in plot. That is, the plot in Natalie’s Glasses is very sophisticated and complex, and adult readers will easily engage with the text on multiple levels. For example, I found myself stopping to view the artwork in an effort to make deeper and more full connections with the text. Additionally, I found myself making associations between Natalie’s struggle and those of Emily Carr, I contemplated Natalie’s encounter with Cyrl and the metaphorical message this conveyed, and I found myself questioning the wisdom of adults when they’re portrayed as often ignoring the perspectives and experiences of the young and elderly.

Even though this very complex plot masterfully illustrates the often confusing jumble of thoughts and experiences a grade four may carry around with her/him when struggling with big issues (such as the closure of “their” school), I believe that the plot complexity of Natalie’s Glasses also impedes the strength of the story and central message. That is, the crisis of being caught in fog without a compass, the crisis of the impending school closure, the crisis of Natalie’s losing her glasses and dreaming she talks to a Redfish who needs them more, the inability of adults to take children seriously, and other issues, seemed to compete with each other and not make strong connections with the main message. In fact, I felt these competing themes and crisis tended to muddy the clarity and impact of central message.

Natalie’s Glasses is a complex story that captures a very important struggle occurring across many rural communities in Canada, communities that are finding it difficult to maintain their schools in the face of declining enrollments and the questionable perception that ‘modern’ schools mean more effective schooling. Although children may not pick up this book on its title alone, and some may find the complex plot muddies the strength of the story’s central message, it is a story that parents and teachers can read and explore with their children in an effort to help children engage with, and make sense of, larger questions and issues facing their children and their communities.

Recommended with reservations.

Keith McPherson, an elementary teacher and teacher-librarian in BC since 1984, and is currently a lecturer for the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- February 17, 2012.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |