| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XVII Number 37 . . . . May 27, 2011

excerpt:

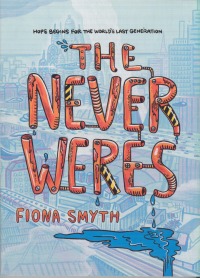

The year is 3088, and the stories that Sasha is re-telling were programmed into her memory nearly a millennium past. The "metropolis" of Fiona Smyth's graphic novel, The Never Weres, is none other than the city of Toronto, now changed substantially. Some of the change is demographic: the Eaton Centre is crowded with "oldies"(people in their sixties), and in the food court, Big Macs ™ and sub sandwiches have been supplanted by torta, udon noodles, all-day dim sum and bubble tea. Thanks to climate change, the sun rarely shines, rain and humidity are constant, and food is really expensive. Cloning offers a possible solution to the population decline, but the horrifying results of past experimentation have driven scientific research underground, "keeping human cloning as an illegal pursuit." (6) Globally, the social fabric is fraying, and locally, "the occurrence and ferocity of protests and riots are on the rise. Anarchists, anti-government militias, and end-of-the-world cultists commonly take to the streets. But no groups clash more than the pro- and anti-cloning activists." (21) Humanity seems doomed. Although the bleak, pessimistic dystopian outlook is not new to futuristic fiction, it's uncommon to see the concept explored in literature aimed specifically at a teen audience. What would it be like to be a member of the last generation of teens on Earth? After my first reading of the book, I decided to invite Gregory Smilski, a Grade 9 student (only a year younger than the protagonists of the novel), and an avid reader (especially of graphic novels) to read The Never Weres and to provide a response to his reading. In the following review, Gregory's comments will be presented in italic font. One of the more unusual aspects of this novel is that the three teens are all equally strong characters; "They each seemed to have their own personalities and opinions and they stuck to them". Although they attend the same high school (and they are all really bright), they come from radically different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds. Jesse is an affluent white Rosedale resident whose mother worked on a very controversial genetic mutation research project, and whose scientific interests mirror those of his now-divorced parents. Mia is an aspiring young artist of Caribbean background who volunteers as an art therapist at St. Anthony's senior citizens' centre where she has a special friendship with an elderly client named Mrs. Campbell. Xian is an edgy, Asian-Canadian computer wizard who lives in a housing project, alone but for her robot cat; her parents died in an airplane crash and her older brother works for a mining company on Mars. Each of the three has a very different perspective on life: Mia is hugely compassionate towards the "oldies" and the physical and mental decline they experience; Xian is totally focussed on the "bots" and technology, and Jesse sees cloning as the only hope for the future. Gregory commented that it was good that the opinions of the three main characters gave us multiple ideas for what to think of the problems of the future. Xian scavenges electronic "garbage" dumped throughout the city (that's where she obtained the parts to build her e-pet, Loly), and one of her haunts is a set of underground tunnels where a mysterious, graffiti-like "tag" keeps appearing. And this is where the story gets complex, as the three friends alternately fight and co-operate to solve the mystery of the "tag" and its connection with the story of Amelia Brown, a 15-year-old who disappeared from a Toronto hospital nearly 60 years ago. Was Amelia "kidnapped by a sicko? Did she run away with a boyfriend? Was she eaten by some kind of urban-myth zombies?" (61) What's down there, besides the City of Toronto's waterworks? Is there any truth to rumours of the remains of secret research labs in which cloning experiments took place. And why does Mrs. Campbell become so agitated when asked about her drawings? The answers emerge more than a hundred pages later, after the story takes more twists and turns than the tunnels of underground Toronto. Gregory commented "I liked the concept of the story. Although the idea of the human population dropping, and in danger of extinction is not a new one, I found the idea of cloning very original." He noted also that "the dystopian, futuristic city reminds me of The Hunger Games and The Matrix. Personally, I thought that Storybot Sasha's appearance looked a bit like the creatures in the movie Avatar". As a former high school English teacher who led (or was that "dragged"?) countless classes of Grade 11's through Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, I think that The Never Weres offers a more accessible look at a future in which "normal" age demographics have changed drastically. However, neither Gregory nor I were satisfied with the book's conclusion, in which cloning becomes legal and humanity is rescued from the brink of destruction by the creation of a new generation of clones who begin life at adolescence. Childhood, as we knows it, "becomes mythic, lost, as new life is found." (234) Gregory stated: "I did not like the ending. I found it too perfect and unrealistic. As soon as cloning was legalized, all controversy seemed to disappear. This would not be realistic because, despite the fact that cloning would be safe, arguments like ‘it's not moral' and ‘it's not natural' would still be present."

Although the Press Release from the publisher suggested that readers of age 10 and older are the intended audience, both Gregory and I agreed that the audience is more like age 12+. Younger readers aren't going to understand the nuances of the cloning issue, and, at times, the language of the text was quite sophisticated. Neither of us thought that the book would appeal much to adults, but I did notice a few clever allusions that a younger reader might not catch: in one frame, an "oldie" is wearing a "Bieber" t-shirt, and the movie night at St. Anthony's features a screening of Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (121).

I especially appreciated Gregory's observations on the way in which Smyth used both text and graphics to tell her story. Although Gregory thought that Smyth was a good artist, he commented that he "found paneling and text boxes confusing. In pages where one large panel was the background for other panels, sometimes the panels were placed in an order that did not make sense." There's a great deal of detail in many of the panels, and it takes successive re-reads to catch them all. When I first read the book, I didn't much care for the black/white and grey tones of the graphics. On reflection, I now realize the grey tones are perfectly appropriate for a story in which the future looks bleak. My co-reviewer commented that "the lack of colour did not hinder the story in any way. I found that it gave me the ability to imagine the setting in my own way. It helped make the story more real to me. Both of us independently arrived at a final "highly recommended" rating of 3 ½ stars. I think that The Never Weres would be a good choice as a senior high school library acquisition, especially as an accessible "read-alike" for students struggling with classics such as Brave New World and The Handmaid's Tale. I'll leave the final comment for Gregory: "The story was very interesting and posed a very good question: ‘Would the cloning of humans be good if it was the only way to survive?'" Highly Recommended. Joanne Peters, who lives in Winnipeg, MB, is a recently retired teacher-librarian. Gregory Smilski is a Grade 9 student at Bishop Allen Academy in Etobicoke, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 27, 2011.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |