| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XVII Number 24. . . .February 25th, 2011.

|

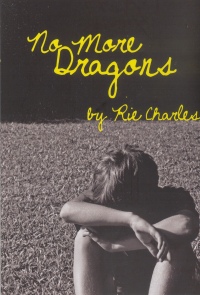

No More Dragons.

Rie Charles.

Toronto, ON: Napoleon, 2010.

114 pp., pbk., $9.95.

ISBN 978-1-926607-12-2.

Grades 6-9 / Ages 11-14.

Review by Ellen Wu.

**1/2 / 4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

...I suggested we put on a play for Mom, Dad, Grandma, and Uncle Peter and Aunt Marion [...]. We got one of Margie’s old story books called There’s No Such Thing as a Dragon. She bought it for five cents at a garage sale years ago. It’s all tattered. But she still likes reading it, especially to Tobey.

We had to change it around a lot. Tobey got to be the mom, because all he had to say was “There’s no such thing as a dragon.” Margie of course had to be the dragon. I was the narrator and general organizer.

We practiced it all morning. We had Tobey dressed in an apron. He just roared around saying over and over, “There’s no such thing as a dragon,” pretending to vacuum, pretending to serve dinner. I’m always amazed how well he gets around, despite being blind.

...

After dinner we went to the living room and performed the play. Everyone clapped and laughed uproariously. Even Dad seemed to be enjoying himself, although Grandma had to keep shushing him because he kept making remarks.

I think I’m going to call Dad the dragon in the house. I wonder if it’s the same thing. The more we don’t talk about what he’s like and the more he gets his own way, the bigger a dragon he gets.

I forgot to tell you--we did go to grandma’s for Christmas dinner. Dad got his way as usual. And Mom, as usual, didn’t stand up for herself. When she asked him to help set the table, he refused. Even Grandma suggested he help, because she gets tired quickly, but he just lounged around and watched TV. Mom did all the food preparation, and I looked after the littlies. We went out and made snow angels and played board games in the spare bedroom. It was okay.

Why doesn’t Mom ever stand up for herself? Why does Grandma mostly give in to him too?

Rie Charles’s No More Dragons is a series of letters written by the main character, thirteen-turning-fourteen Alex Crispin, to his friend Graham. They chronicle daily life in the countryside in the Canadian Shield: taking care of his younger siblings, the “littlies,” discovering his passion for writing and acting, learning to stand up for a bullied boy at school who ends up becoming his new best friend. His epistles are simple, frank accounts of his baby brother Tobey’s struggle with cancer, overshadowed at times by one of the central concerns of the novel: his father’s hostile bullying and abuse of the family. Graham is Alex’s only friend. Too bad he is an imaginary one.

Charles’s No More Dragons is a deceptively straightforward account of a tumultuous period in Alex’s life, dealing with serious issues without over tipping the balance from pathos into melodrama. A sensitive, lonely boy with no one to confide in but Graham, Alex is the type to prefer writing in his attic room to hockey. He is constantly berated and abused, both verbally and physically, by his father, who dominates the entire household with his unpredictable temper. His mother, soft-spoken to the point of voicelessness, has to take care of the children and manage the household, one of whom is dying of cancer and needs constant medical attention, but she is still yelled at and physically hurt for the most arbitrary of reasons (or no reason at all).

Things are changing for Alex, though, as he confronts what he considers his lack of courage and grows. In seeing how a new schoolmate is resilient in the face of bullies, Alex soon dares to stand up to them, too, in defense of his younger brother, nearly blind due to cancer, or the bullied friend, Bennie. Alex assumes an alter-ego at times, calling himself “Mac,” a boy with acting chops, whom he invests with the talents and confidence he feels he lacks. Alex knows that his father is the ‘dragon’ in the household, getting bigger and bigger in size the more his tyrannical behaviour is ignored. At one point, after a trip to church, Alex mulls over what he heard in the sermon: “You can’t be afraid of someone you love“ (76). Does Alex hate his father? Alex can’t answer the question himself, but he responds to it with another question of his own: “How can I love my dad if he I’m afraid he’s going to hit me,? Or hit Mom?” (77). Standing up to school bullies is one thing. Can Alex summon up the strength to stand up to the biggest bully he faces of all?

Alex makes the choice he knew he would all along when his father rampages after his little sister, Margie, shortly after the death of his baby brother, Tobey. Alex, his sister, and mother escape by a hair’s breadth, and seek refuge at a woman’s shelter.

The letters to Graham so faithfully kept up over the months, which provided a kind of therapeutic outlet for Alex, draw to a close, as Alex puts the last one aside, to one day “read them all again,” to remember how he was (114). He has real friends now, and also, real strength to be who he wants to be. He has kept faith with his beloved brother Tobey whose death he still grieves and won’t recover from for a long while. Charles realistically captures the ambivalent feelings that Alex has: some days, Alex thinks it will be easier to have his father come back than to face the challenges of growing up in a single-parent home. Other times, and more often, he knows he made the right choice. No matter what though, the reader is assured that Alex, tested in his character by adversity and loss, is ready to face whatever comes next for him.

This is an important, if at times troubling, novel for young people to read and may serve the purpose of bibliotherapy in demonstrating one young boy’s journey from emotional fragility, in a situation of domestic abuse, slowly attaining self-belief and strength. While its epistolary nature precludes a more quickly paced plot, the point is for the reader to empathize with Alex and at least be aware of the issues raised in the book. The narrative is seldom heavy handed, with the grave issues of domestic abuse and cancer alleviated by lighter subjects, such as Alex’s discovery of his love and gifts for acting and writing. Nevertheless, Charles’s description of Alex’s father still veers toward frightful caricature at times, rather than a more nuanced portrait of a troubled and violent man, as he growls over not having his preferred dessert, or berates Alex for not playing his best at hockey. That portrayal, however, does not take away from rich inner life of Alex, the discovery of his inner strength, and his faith and capacity to love and protect his family.

Recommended.

Ellen Wu holds a MFA in children’s literature from Hollins University in VA, and is a MLIS student at the School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies at UBC.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to

cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE- February 25, 2011.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |