| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVII Number 13. . . .November 26, 2010

|

Harvey.

Hervé Bouchard. Illustrated by Janice Nadeau.

Translated by Helen Mixter.

Toronto, ON: Groundwood/House of Anansi Press, 2010.

168 pp., hardcover, $19.95.

ISBN 978-1-55498-075-8.

Grades 3-8 / Ages 9-13.

Review by Dave Jenkinson.

**** /4 |

| |

|

excerpt:

For me, the first spring is the time when my boots get heavy and slow me down.

I don’t know how it happens, but when spring comes, they suddenly get too big, the laces grow and hang down and my feet drag with every step.

And I’m hot and it even seems that my sleeves get longer. But this time of first spring is also the time when Cantin and I lost our father Bouillon.

And it’s the time when I became invisible. So there are lots of things to tell.

Harvey is the first book to win the Governor General’s Literary Award for both text and illustration. Originally published in French in 2009, this moving graphic novel about encountering death and dealing with grief is now available to an English audience via translation. The double GG award was truly merited as Bouchard’s text and Nadeau’s illustrations blend together seamlessly, almost like two harmonizing vocalists. Harvey is Nadeau’s third GG Award for illustration since 2004.

The book’s first five double-page spreads are wordless and function like the opening shots in a movie, shots that establish place and time as the camera begins with a long shot and then pans before focussing in on something important. In this case, the establishing shot reveals the setting to be a snow-covered hilly rural area in which can be found a small village. As the “camera” comes closer, viewers see a young boy riding a bicycle, and he simply identifies himself (“Everybody calls me Harvey.”) and then establishes the time setting (“My story begins just at the end of winter, at the very first beginning of spring.”). Harvey has a younger brother, Cantin, but because Cantin is taller than Harvey, “everyone thinks I’m the little Bouillon. And everything I wear he wore first.” The book’s first five double-page spreads are wordless and function like the opening shots in a movie, shots that establish place and time as the camera begins with a long shot and then pans before focussing in on something important. In this case, the establishing shot reveals the setting to be a snow-covered hilly rural area in which can be found a small village. As the “camera” comes closer, viewers see a young boy riding a bicycle, and he simply identifies himself (“Everybody calls me Harvey.”) and then establishes the time setting (“My story begins just at the end of winter, at the very first beginning of spring.”). Harvey has a younger brother, Cantin, but because Cantin is taller than Harvey, “everyone thinks I’m the little Bouillon. And everything I wear he wore first.”

One of the things that Harvey likes about spring is that he and his school friends can race their toothpick “boats” in the gutter, and that’s what Harvey, his brother and five of their friends are doing on this April day after school.

I colored the end of my toothpick red so I could tell it from the others and I put a tiny gray dot right in the middle. The gray dot is Scott Carey. I’m the one in charge of coloring everyone’s toothpicks so that each one is different.

While Harvey wants to do his usual play-by-play narration of the race, his idea is squashed by the others who also tease him about his short stature. Not completely deterred, Harvey “announced the race inside my head just for me, making Scott Carey look good.” Harvey’s “boat” gets hung up and finishes so far behind the others that only he and Canton are present when “Scott Carey plunge[d] into the drain.”

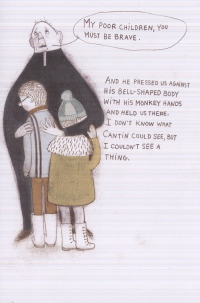

When the brothers arrive on their street, they find a quiet crowd assembled outside their home and “an ambulance stood in front of the house with its light flashing.” Intercepted by the priest, the boys are prevented from seeing what’s happening, but Harvey does hear his mother “calling out the name of my father Bouillon,” and he manages to sufficiently escape the priest’s grip so that he can see the ambulance attendants putting a stretcher bearing a blanket-covered body into the ambulance. After the ambulance departs, the book uses five double pages to show the crowd silently dispersing so that finally only Harvey’s mother is seen alone against a completely white background.

The story then moves into the house where three wordless dark spreads are followed by a fourth that simply reads, “Of course, my father Bouillon wasn’t there.” Harvey’s mother explains to her sons “about Father’s heart attack. And that it was over and that in Heaven everything was all right and that she was going to lie down now....” With his mother taking to her bed essentially until the funeral, it is up to Harvey to explain to Canton why his father is not in the house. That night, as Harvey stares at the slats of Canton’s bunk bed above him, he sees “a tiny dot that only I recognize. It’s Scott Carey.” For the next 16 pages, Harvey retells the plot of The Invisible Man, a 1957 black & white movie that Harvey had once secretly viewed by hiding in the hall and watching it on TV while his parents thought he was in bed. For Harvey, the critical point of the movie occurs when Scott Carey becomes so small that he becomes invisible, but Harvey “knows” that “Scott Carey keeps on living his life. He’s alone in the night, face to face with the stars.”

For the remainder of the book, the setting shifts to the funeral home, and readers see the two days of “viewing” through Harvey’s eyes. He overhears the mourners commenting on his dead father`s appearance in the coffin, and in his mind (and illustrated by Nadeau) Harvey creates some two dozen pictures of his father`s face, each a literal interpretation of someone`s comment. Finally, the time comes for the coffin’s lid to be closed. “It was the time for the big separation. Because afterward you would never see the person inside again.” While Harvey doesn’t want his brother to take this last look because Harvey doesn’t think the body in the coffin represents the real father he knew, Cantin does so anyway. Left alone, Harvey is hoisted onto his uncle’s shoulders and, over five wordless spreads, Harvey disappears. Like Scott Carey, Harvey can no longer be seen, but the reader will recognize that he still exists because it was Harvey who just narrated the story.

The juxtaposition of Harvey’s carefree childhood activity with the sudden harsh reality of death results in the book’s having a powerful emotional impact, especially as Harvey becomes invisible in the adult world that is carrying out its death-related rituals. Harvey is a very quick read, but the ending may leave some readers somewhat confused. Hopefully, readers will recognize that this book merits more than one reading so that they can plumb the meanings of the metaphors imbedded in the text and illustrations. Bouchard’s text is appropriately rendered in a font that resembles a child’s printing. Nadeau’s uses a limited colour palette, but her somewhat cartoonish illustration, coupled with the book’s design, effectively reveal the characters’ emotions. For young readers who are unfamiliar with the film The Invisible Man, a version can be located on the Web.

Highly Recommended.

Dave Jenkinson, CM’s editor, lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- November 26, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |

|

The book’s first five double-page spreads are wordless and function like the opening shots in a movie, shots that establish place and time as the camera begins with a long shot and then pans before focussing in on something important. In this case, the establishing shot reveals the setting to be a snow-covered hilly rural area in which can be found a small village. As the “camera” comes closer, viewers see a young boy riding a bicycle, and he simply identifies himself (“Everybody calls me Harvey.”) and then establishes the time setting (“My story begins just at the end of winter, at the very first beginning of spring.”). Harvey has a younger brother, Cantin, but because Cantin is taller than Harvey, “everyone thinks I’m the little Bouillon. And everything I wear he wore first.”

The book’s first five double-page spreads are wordless and function like the opening shots in a movie, shots that establish place and time as the camera begins with a long shot and then pans before focussing in on something important. In this case, the establishing shot reveals the setting to be a snow-covered hilly rural area in which can be found a small village. As the “camera” comes closer, viewers see a young boy riding a bicycle, and he simply identifies himself (“Everybody calls me Harvey.”) and then establishes the time setting (“My story begins just at the end of winter, at the very first beginning of spring.”). Harvey has a younger brother, Cantin, but because Cantin is taller than Harvey, “everyone thinks I’m the little Bouillon. And everything I wear he wore first.”