| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVII Number 1. . . .September 3, 2010

|

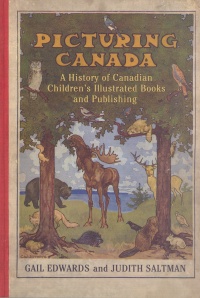

Picturing Canada: A History of Canadian Children's Illustrated Books and Publishing.

Gail Edwards & Judith Saltman.

Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

381 pp., pbk. & hc., $39.95 (pbk.), $95.00 (hc.).

ISBN 978-0-8020-8540-5 (pbk.), ISBN 978-0-8020-8759-6 (hc.).

Subject Headings:

Illustrated Children's books-Publishing-Canada-History.

Children's literature, Canadian-History and criticism.

Children-Canada-Books and reading.

Professional.

Review by Gregory Bryan.

**** /4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

When children in centuries past picked up illustrated books with Canadian subject matter, they usually saw a reflection of the country in texts and images created by expatriates, visitors to Canada, and armchair travellers, published in Britain and the United States for middle-class domestic readers fascinated with the exotic and unfamiliar. These publications, written from the metropolitan centre, draw on the literary traditions of travellers' tales, pioneer and emigrant narratives, outdoor adventure and survival sagas, in an imaginative recreation of the colonial space as a romantic and alien wilderness, very different from the urban domesticated social space inhabited by the reader. (p. 17).

Picturing Canada: A History of Canadian Children's Illustrated Books and Publishing is a major undertaking by Gail Edwards and Judith Saltman. As the book's full title makes clear, in Picturing Canada, Edwards and Saltman provide a history of illustrated Canadian books for children, from the earliest days of the genre through to the present time.

The authors not only come well qualified for the task that they have undertaken, but they represent an interesting combination, with Edwards' specialization in history and Saltman's specialization in children's literature. Edwards is the chair of the Department of History at Douglas College, BC, and Saltman is an associate professor in the School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies and the chair of the Master of Arts in Children's Literature Program at the University of British Columbia. They write with authority and with a close eye for detail. They write also with a precision that makes their arguments logical and persuasive.

Picturing Canada consists of nine chapters. The book is arranged both chronologically and by themes, with a focus not just on the picturebooks themselves, but also upon the related history of Canada and of Canadian childhood. Picturing Canada is almost 400 pages in length, but over 150 of these pages comprise the book notes, bibliography and index. There is also a nine-page chronology entitled Children's Print History in Canada. There are almost 70 pages of notes. Given such precise, academic attention to detail, this book is not intended for wide, everyday readership. It is a scholarly resource and, when approached as such, readers will find the information that they want is accessible, and, although skewed in their direction, the book need not be limited only to academics.

Black-and-white illustrations (excerpts from children's books) are sprinkled throughout the text. Twenty colour plates are also included. These illustrations help the reader to appreciate and understand Edwards' and Saltman's discussion of various books and publishing/illustrating trends.

Chapter one is an introductory chapter in which Edwards and Saltman begin by discussing, defining, and distinguishing between picturebooks and illustrated books. This is followed by a discussion and definition of what the authors mean by the terms "Children's books" and "Canadian." This detailed, precise approach sets the scholarly tone for the remainder of the book.

Chapter two traces the history of Canadian children's books from the genre's beginnings through to the 1890s. Throughout this period, the primary focus was on what Edwards and Saltman term the "Otherness" of Canada. That is, in materials for children, Canada was portrayed as "a place of ice and snow, dark and dangerous wooded forests, infinite prairie expanses, and towering mountains, populated by mysterious, savage, and primitive peoples and dangerous wild animals" (p. 17). Canada was presented as a place free from the constraints imposed by the so-called civilized societies that existed in Britain and in the United States. Canada was a setting for wilderness escape and adventure, and, we learn, by the end of the Nineteenth Century, Canada was one of the most popular settings for illustrated boys' adventures stories. Amongst other titles in chapter two, reference is made to early works such as Northern Regions: or, A Relation of Uncle Richard's Voyages for the Discovery of a North-West Passage (1825), A Peep at the Esquimaux; or, Scenes on the Ice (1825), and Little Grace, or, Scenes from Nova Scotia (1846).

Of particular interest in chapter two is the discussion of the life and work of Amelia Frances Howard-Gibbon. One of the most prestigious of all Canadian children's literature awards is named after her. Another who receives individual attention is Ernest Thompson Seton, who is credited with developing the genre of wild animal biographies, focusing on animals in their natural habitat. Influenced by Seton's work, Edwards and Saltman tell us, as the Nineteenth Century drew to a close, Canada's wilderness began to be portrayed less as a place to be feared, and more as a place to be "celebrated, embraced, and protected" (p. 29). Given today's world-wide appreciation of the beauty of Canada's out-of-doors, Seton's work represents a significant moment in Canada's history.

Chapter three describes and discusses the period from the 1890s through to the end of the Second World War. This period was characterized by increasing technology, including within the children's book industry. There was large growth in the industry in Britain and the United States, but the Canadian industry remained small, with the few publishers that did exist having trouble finding a market for their work. One very bright light in Canadian children's literature from the time was, of course, L. M. Montgomery with Anne of Green Gables (1908).

Despite the success of L. M. Montgomery, the financial hardships of the Great Depression of the 1930s caused what Edwards and Saltman describe as the "near-collapse" of Canadian publishing for children (p. 50). Despite this, a significant development from the first part of the Twentieth Century and through the 1930s was the emergence of children's librarians within public libraries. With the children's collections in public libraries growing, positions were made for children's literature specialists on library staff. In 1939, the Canadian Association of Children's Librarians was formed.

The enigmatic Grey Owl is also discussed in the third chapter. His children's book, Sajo and her Beaver People, was published in 1935. As with his other books for adult readers, Grey Owl conveyed a strong environmental message with his children's book.

In chapter four, discussion centres on the postwar period. William Toye and Elizabeth Cleaver are credited with what Edwards and Saltman describe as the "first true picturebooks published in Canada" (p. 59), producing books in the late-1960s and through the 1970s.

Although children's books had been reviewed in Canada before this period, it was not until In Review began publication under the editorship of Irma McDonough that the Provincial Library Service of Ontario established the first journal to "systematically" review Canadian books for children (p. 66). In Review was published from 1967 until 1982 and is described in Picturing Canada as a key figure in not only describing and reviewing the Canadian children's book scene, but also in improving its quality.

Canadian publishers are described by Edwards and Saltman as entering the 1970s with a sense of caution in terms of developing their lists of children's titles. This caution was largely supplanted by the decade of development which is the focus of chapter five. At the start of the decade, imported children's books accounted for over 90% of Canadian sales, but the number of Canadian-produced books increased as the Canadian children's book industry experienced important development through the 1970s. The 1970s saw the establishment of what are today important publishing houses like Annick Press, Tundra Books, and Kids Can Press, among others. A number of new children's literature awards were also instituted during the 1970s. These awards not only served to acknowledge good work from authors, illustrators and publishers, but they also helped to provide monetary compensation and reward for excellence. This is significant given the interesting chapter five discussion of the struggle for credibility for children's book illustrators. Within the world of art, illustration is depicted as having lacked credibility as an art form. Another important milestone of the 1970s was the development of the Canadian Children's Book Centre. Since 1976, the Centre has served many important purposes. Among other purposes, the Centre has served as a research depository for Canadian children's books, the organizer of the Children's Book Festival, and publisher of the journal, Canadian Children's Book News.

An important name that is discussed in chapter five is that of the poet, Dennis Lee. Lee's Alligator Pie (1974) was a big seller that helped to establish the commercial viability of publishing material for children. Illustrated by Frank Newfeld, Lee's rhythmic collection of poems was the first Canadian-published children's title to achieve "overwhelming commercial success" (p. 75).

The 1980s are the focus of the sixth chapter of Picturing Canada. The chapter heading denotes this decade as the "flowering" of Canadian illustrated books. The 1980s were a period of rapid expansion and improvement of Canadian materials for children. Among other causes, two things to which this expansion and improvement are attributed are the use of offshore technology and the literature-based movement in schools. The use of offshore companies for printing and binding Canadian authored and illustrated books made available technology otherwise inaccessible. In schools, the whole language move away from the use of textbooks toward classroom use of children's trade books increased the demand for material that teachers could confidently use within their classrooms.

During the 1980s, some big names emerged from the Canadian children's book scene. The author Robert Munsch, illustrator Barbara Reid, and the character, Franklin the turtle, are included for discussion in chapter six. Robert Munsch and his work are discussed in particular depth. The publication of The Paper Bag Princess in 1980 is said to have made him the "first contemporary superstar of Canadian children's literature" (p. 108). Additionally, his best-selling Love You Forever (1986) is discussed in detail. The book is identified as the "best-selling Canadian picturebook of all time" (p. 125), but Edwards and Saltman include a fascinating discussion of the diametrically opposing viewpoints held by readers who are described as either loving or hating the book.

Another significant landmark of the 1980s is the emergence of small Aboriginal-owned and run publishing houses. Theytus Books and Pemmican Publishing began to provide a venue for authentic indigenous stories, as well as to give voice to Aboriginal, Métis and Inuit authors and illustrators in telling their stories.

Chapter seven and chapter eight are dedicated to the period from 1990 until the present. Chapter seven is subtitled Structural Challenges and Changes. I personally found this chapter to be the most interesting of the whole book. While the chapter was interesting in that it describes the current situation, I also found the topics for discussion, and the manner in which the discussions were written, was particularly interesting. The challenges and changes of the past 20 years are identified as including an increased publishers' emphasis on commercial success juxtaposed against—or inspired because of—increasingly difficult economic times. Within this difficult economic environment, the challenges of the past 20 years have also included decreases in government funding, reduced public library spending, and a sharp fall in the numbers of teacher-librarians. At the same time, increasing book costs have caused consternation among some consumers. In many schools, the 1990s also saw a movement away from literature-based teaching toward the use of materials other than trade books for reading instruction.

As a book reviewer myself, I was also particularly interested by the discussion of children's book reviews. The past 20 years have seen a large decline in the number of reviews of Canadian books in sources such as newspapers and magazines, at the same time as the proliferation of reviews by what are described as "non-expert communities of readers" (p. 152) in online Internet sites. Another interestingly presented discussion is the increasing numbers of awards for children's literature, including the emergence of Canadian young readers' choice awards. Virginia Davis, a former director of the Canadian Children's Book Centre, is quoted as saying that the effect on books sales of these readers' choice awards has been "phenomenal" (p. 148), while Edwards and Saltman say that, "as a way of bringing children and books together, the readers' choice awards…have been an unqualified success" (p. 149). Additionally, the 1990s saw the decline of many independent bookstores, while (and partially because) Canada's two largest bookstore chains, Coles Book Stores and SmithBooks, merged in 1995 to create Chapters, Inc..

Chapter eight is used to continue the discussion of the Canadian children's literature scene from 1990 through until the present, but this chapter focuses on specific titles from various Canadian publishers. Some of my own favourites that are discussed to varying levels of depth in the chapter are Orphan Boy (Mollel, 1990, Oxford Canada), Something from Nothing (Gilman, 1992, North Winds), Ghost Train (Yee, 1996, Groundwood) and Kids Can Press' "Franklin" series (Bourgeois & Clark) and the artistic visual re-imagining of classic poems in the "Visions in Poetry" series of books. In the introductory comments for the chapter, the past 20 years are described as a time in which Canadian publishers have sought to "push the boundaries" and employ "more adventurous book design" in their picturebooks and illustrated books (p. 153).

Edwards and Saltman focus on the notion of Canadian identities in chapter nine. They explore the idea of what it is to be Canadian. Illustrated books and picturebooks are discussed in terms of providing a reflection of Canadian norms and values. This discussion is, of course, a complex one given the diversity of contemporary Canada, and Edwards and Saltman do a good job at presenting varying perspectives from people looking from different vantage points. The issue of appropriation is discussed in particular depth and, as one who wonders aloud about this issue in teaching my university children's literature classes, I found this section enlightening as well as interesting. The discussion of different story-telling techniques and patterns is also noteworthy and informative, particularly when considered in terms of how these different approaches to the telling of stories might impact the bottom line of commercial viability in publishing. Furthermore, I was also intrigued to read in chapter nine about the changes to text and illustrations that sometimes occur when Canadian material is subsequently republished in the United States of America. Chapter nine involves a shift in focus for Edwards and Saltman. It is a strong addition to the book, but it certainly can stand alone and allow a reader to read the final chapter without having read the preceding chapters.

One hundred and thirty-six "industry" people (writers, illustrators, publishers, editors, children's literature academics, and the like) were interviewed for the book. The authors also examined 573 award-winning Canadian children's illustrated books published in Canada between 1947 and 2005.

As mentioned earlier, the book consists of many pages of end notes. One of the many design features that I found to be extremely helpful was the page header indicating the relevant main text pages to which each page of notes corresponded. I found this to be helpful on those several occasions when I wanted to flip back to check a note or two.

This book is not for everyone. It is a scholarly resource, and many will find the information and presentation dense and perhaps occasionally cumbersome. For those with a scholarly interest in the topic, Picturing Canada is an invaluable document, and the authors and University of Toronto Press are to be congratulated for their efforts in producing such an important chronicle of a special part of Canada's historical record. Others with more of a passing interest in the topic will, however, also be able to use the detailed index and the table of contents to locate the information they seek. The research for Picturing Canada was funded in part through a Frances E. Russell Grant administered by the Canadian branch of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY Canada). IBBY Canada can consider the grant money well earned.

Highly Recommended.

Dr. Gregory Bryan is a professor of children's literature at the University of Manitoba.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- September 3, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |