| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVI Number 36. . . .May 21, 2010

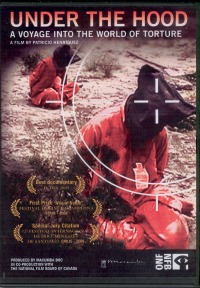

So often on movies and television shows, when the bad guy is being uncooperative under questioning, the good guys will apply some physical pressure to persuade and the answers come out freely. Whatever nefarious plot is in the works is thwarted, and the show cuts to a happy ending. Sadly, this mentality carries over to the real world, and, in many cases, people believe that the end justifies the means. If torture is required to get answers, then torture should be applied. Under the Hood looks at the use of torture not in a philosophical way, but through the eyes of those who have been victims of such acts. In all cases, the torture did not yield any information as those tortured had nothing to reveal. That fact, however, did not save them from suffering. When Mourad Benchellai’s brother suggested he take advantage of a summer camp being offered in Afghanistan, the idea sounded appealing. The older brother had gone already and said that all the information about the Taliban in the news “was fake. They are good people.” While his parents came from Algeria, Benchellai had spent all his life in France. After his arrival in Kandahar, he and many others were taken to a camp where he found out that they were to undergo military training. He recalls the day when Osama bin Laden came to speak at the camp. Since the speech was going to be in Arabic, Benchallai did not attend as he would not have understood. Days later, the attack on the World Trade Centre happened, and Benchallai decided to get out of Afghanistan. Once across the border in Pakistan, he was taken and ultimately sent to Guantanamo. Said Nabi Sidiqy an Iraqi police sergeant, arrived at work and was taken by surprise. He was stripped of his police uniform, blindfolded and led away. Abused, sexually tormented and nearly beaten to death, his torture lasted 15 days during which he was asked, “Which warlords do you know?” and “Do you know Fidel Castro?” Jamal Gal was arrested and tied up outside his own home alongside his 94-year-old father. He was held for 10 days during which he was marched hooded. They “beat me a lot and did unimaginable things.” He was never formally interrogated, but “seven or eight Americans took turns beating him up.” From there, he was sent hooded and tied for more questioning. The torturers were trying to link him to the Taliban, but he preferred torture to making things up: “I did not want to confess to what I’d never done.” After a year of imprisonment, but no further questioning, Gal was told that they could find nothing on his file. He would have been released sooner, but his actual file ended up on the bottom of a pile and forgotten. Gal knows who gave his name to the authorities. Often during personal disagreements, the best way to settle a score is to offer one’s adversary’s name as a possible threat. There is reward money for turning in people. Finally released after more than three months, Gal was given an apology for their having wasted his time. Sidiqy was also released in time, with an apology stating that his arrest was based on wrong information. He thought, “The Americans came to make peace, but why do they act like this?” El Haj Ali Al-Kaissi, retired teacher and village regional chief, was arrested and taken to Abu Ghraib prison——now famous for the photographs that showed the forms of torture used against the inmates. Al-Kaissi was tied to his cell door and had “indecent English words written on my body.” Interrogators from private companies arrived. “They came from everywhere……different nationalities.” He was told to confess, give names and collaborate, “or they’d torture with electricity.” He was placed on a box, as shown in the famous Abu Ghraib photos, with his hands and feet wired. “Suddenly I saw a yellow flash……my teeth were chattering. It felt like my eyes were coming out of their sockets.” At another time, when he asked for treatment for his wounded hand, a guard crushed it instead. The film shows many more photos from Abu Ghraib, each more disturbing than the one before. Abu Ghraib shocked the world, but there were 13 other prisons just like it. While 10 soldiers were convicted for their actions at Abu Ghraib, no higher officers were punished. In an attempt to understand the behaviour of the guards, the film looks at those who were on the other side of this treatment. Sean D. Baker Sr. was retired, but he re-enlisted after 9/11. Eager to do his part, he was told he was going to Cuba. “Cuba? What the hell’s in Cuba?” Initially he was told that the inmates at Guantanamo were “all terrorists of the worst kind——they don’t deserve to breathe air, but we are going to do the righteous thing——try them and convict them. This will prove to the world that they deserve to be where they are.” Baker states that, at first, he treated the prisoners as all the same and followed his training. However, “You get individuals who want to lay down their lives for their cause. It’s hard to break that man’s soul when he believes so deeply. It’s hard to find an American who believes that way. I almost respected them for that.” Baker volunteered for a special extraction exercise whereby he was to wear an orange jump suit and pretend to be a prisoner. He was instructed to be as difficult as possible as the guards try to drag him out of a cell. He was assured that, if things turned ugly, he had a code word that would stop the exercise. During the extraction, he was choked by the guard. When he gasped out the code word, his head was slammed to the floor. When he tried to explain that he was a soldier, his head was slammed to the floor again and he lost consciousness. The guards were never told that he was a soldier. In fact, they had been instructed that he had already assaulted a guard and a sergeant. He is later shown wearing a neck brace in his hospital bed. He has constant “terrible, horrible headaches with nightmares every night” and his “screaming would startle and wake his son.” Government sanctioned torture is nothing new and not restricted to the post 9/11 world. Throughout the film, references are featured from the Kubark Counterintelligence Interrogation: The CIA’s Manual on Corrective Questioning 1961: “The principal coercive techniques are arrest, detention, the deprivation of sensory stimuli, threats and fear, debility, pain, heightened suggestibility and hypnosis and drugs.” Each case featured seems to be following the text to the letter. Sister Diana Ortiz, an Ursuline nun and outspoken critic of torture, points out that torture has been used in “Peru, Viet Nam, Philippines, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina——all where the U.S. has been involved——if not directly then by supporting that particular government.” Sister Ortiz knows firsthand what this means. A teacher in Guatemala, she did not see herself as subversive. However, while at prayer in her church, she was taken by two men at gunpoint. They took off her sweatshirt and said, “Let's play a game. If we like your answer, we’ll let you smoke. If not, we’ll burn you.” Every answer meant a burn--as did silence. Sr. Ortiz was burned 111 times on her back alone. In her book, The Blindfold’s Eyes: My Journey from Torture to Truth, she reveals that of the 200,000 victims in Guatemala, 83% were Mayan. Ortiz was raped repeatedly, but when she was offered to one of her torturers--an American, he is surprised to learn that she was also an American and insisted she be released. She has been trying to find out who this agent was, but, back in the U.S., “No one believed that an American was in the torture chamber and that he gave commands to the others.” No one was ever brought to trial for the killings and not a single military commander has been tried. Under the Hood is clearly a difficult film to watch. Other examples of torture are shown, and each questions our ability to call ourselves truly civilized. The fact that all of them are U.S. state-sanctioned is chilling at best. Interspersed with the stories are quotations from President Bush Jr. who applauds the good work being done in both Iraq and Afghanistan and denies that his government is condoning any torture. If the subject matter was not so serious, his comments would be almost laughable. Kayla Williams, author of Love my Rifle More than You: Young and Female in the U.S. Army, was an intelligence officer in Iraq for a year. During that time, she was called in for an interrogation session. She assumed because she spoke Arabic and was female, she would be dealing with a female detainee. In fact, it was a male prisoner who was told to remove his clothes. He was then subjected to a mocking of his manhood in an attempt to degrade him and break his spirit. Sickened and shocked, Williams reported this to her superior and was never invited to an interrogation again. At the end of the film, she states that, “Torture does not work to extract information. People will say anything to make the torture stop. The ones who really know things are well trained and are able to resist.” Dr. Burton J. Lee, friend of George Bush Sr. during the 1960s and then personal physician to Bush when president, condemns anyone in the medical profession who administer drugs as part of the torture procedure as being “guilty of a terrible breach of medical ethics.” He compares the use of torture to the Spanish Inquisition: “How much good did the Spanish Inquisition do for the Catholic Church? It has left a permanent scar and stain on the Catholic Church for all eternity.” He sees great danger in this practice, and there will be a price to pay: “When you torture one, there is a penumbra of others who will now side with the victim against the torturer.” He questions the value of torture – “Once the main guy is captured, everything he knows will immediately become history”. In its entirety, Under the Hood would be difficult to show in a classroom. It is very long and almost exhausting in its content. However, parts could be used in a History, Law, Ethics, or Politics class. It would certainly work in a Social Justice group or if the school has an Amnesty International group. This is a must for teachers, especially as Canada is being accused of involvement in questionable practices in Afghanistan. Dr. Lee says, we “have to discuss, discuss, discuss, discuss. If you get into a war, nothing works the way you thought it would——ever. When you have a war, anything and everything happens.” Graphic content and images should offend everyone. Highly Recommended. Frank Loreto is a teacher-librarian at St. Thomas Aquinas Secondary School in Brampton, ON.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- May 21, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |