| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVI Number 27. . . .March 19, 2010

|

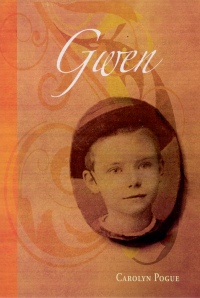

Gwen.

Carolyn Pogue.

Toronto, ON: Sumach Press, 2009.

157 pp., pbk., $12.95.

ISBN 978-1-894549-80-6.

Grades 5 and up / Ages 10 and up.

Review by Ruth Latta.

**** /4

|

| |

|

excerpt:

After the girls have been at the home for a while and learned all there is to know they can work in England or go out to Canada or another colony like Australia and start a whole new life out there. Would you like that, Gwen Peters?" And suddenly I was backstage at the theatre with my dad, listening with all my heart to Pauline Johnson's words and before I knew it I said, 'Yes.' ...

What pulled me up out of the tall ditch grass and onto my feet wasn't the whistle of the next train, it was red rage. How dare he come after me like that! And her, how dare she slap my face! How dare she never say my name! How dare they say I was vermin! How dare they make me eat all alone! Never. Never. Never. I would never return to that house.

Between the 1860s and the 1930s, over 100,000 poor children were brought from Britain to Canada to make new lives for themselves, and one third of them were girls. Nineteenth century industrialization produced urban slums inhabited by a large sub-working class population subsisting in abject poverty. Government programs to ameliorate conditions were unthinkable, given the prevailing laissez-faire economic philosophy of the times. The social safety net in Britain would not be established until after the second World War.

The Church of England and several private philanthropic societies attempted to rescue destitute children, place them in residences (the most famous being Dr. Thomas Barnardo's Homes) and arrange their placement in the former colonies, principally in Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants.

On February 24, 2010, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown apologized to the surviving former "child migrants," saying that sending poor children to the colonies was "not the right thing to do." He acknowledged that the children had been sent away when they were "most vulnerable," that they were "robbed of their childhood" and that their voices "were not always heard." An 83-year-old Canadian woman, in England with her daughter to be present for the apology, told the CBC that she had not been an orphan; rather, her father had left the family, and her mother couldn't cope, and so she and her siblings were sent to Canada.

The placing agencies tried, but largely failed, to supervise the placements and see that the children were receiving proper food, shelter, allowances and education. Consequently, many children were exploited by host families who saw them as "free labour" and "from the gutter." Over the last three decades, these child immigrants have been the subject of nonfiction and fiction writers, and the consensus seems to be that, although many children were badly treated, their lives in Canada were better than their prospects in Britain. They made a significant contribution to the growth and development of Canada. Many served in the Canadian forces in World Wars I and II, and it is estimated that up to three million Canadians are descended from the "child migrants."

One of these Canadians is Calgary children's author Carolyn Pogue who discovered, as an adult, that her grandmother, Gladys Gwendolyn Parsons, came to Canada in 1898 as a "Home" girl at age 10 to work as a servant. The innocent sensitive child's face on the cover of the novel of Gwen is Gladys Gwendolyn's. In choosing to write a novel inspired by her grandmother, not a biography, Pogue gave herself the flexibility to construct a dramatic story.

A real-life person with a cameo role in Gwen is Canadian poet E. Pauline Johnson. Of Mohawk and English parentage, Johnson toured Canada performing her poems on stage, and she took her act to England in 1894 and 1906. She dazzled audiences not only with her dramatic recitations but also with her attire. For the first half of the performance, she wore elegant evening gowns. For the second half, she wore a costume of her own devising which included elements of the traditional clothing of various North American First Nations.

Gwen opens in 1895 when Gwen Peters is turning eleven-years-old. She lives with her widower father in a tenement room in London, England. He is a cleaner at the Steinway Theatre, and, as a birthday treat, he takes Gwen to stand backstage with the curtain operator to watch Pauline perform. (Pogue shifts the date of Johnson's performance from 1906 to 1895 to suit her plot.) Dazzled, Gwen longs to see the Canadian settings that Johnson describes, and she feels inspired to put on more skits in the neighbourhood with her friend Will, a newsboy. When Gwen's father gives her a copy of Johnson's poetry collection, The White Wampum, the little girl is ecstatic—but not for long.

Mr. Peters is in the last stages of a long struggle with tuberculosis, an all too commonplace malaise of that era, but his death seems sudden to Gwen. A neighbour organizes a pauper's burial and contacts Dr. William Allan (based on Dr. Thomas Barnardo), who visits Gwen and tells her of his Girls' Home. There, girls live together in cottages with housemothers, learn cooking, sewing and the three R's, and eventually move to the Dominion of Canada or another former colony.

Pogue's depiction of Gwen's psyche is insightful. Too dazed to grieve, too limited in expectations to object, too used to accepting whatever life deals her, Gwen goes with Dr. Allen in his buggy, feeling as if she is "in a play." A month later the full realization of her father's death hit her.

"Home" life may be new to readers who are more familiar with accounts of the young immigrants' lives in Canada. The author introduces other girls, each illustrating a different set of tragic circumstances that brought her there. Although the residence life is regimented, the regular meals, cleanliness and literacy and numeracy training seem vastly better than life on the streets.

Gwen's journey to Canada is also an education. On the train through Quebec and Ontario a friendly elderly Québecois woodsman shares his bush-lore, knowledge which serves her well later in the novel. She learns, too, that some Canadians disapprove of child immigrants. One editorial says: "We have quite enough paupers and criminals without exporting shiploads from Britain."

Carolyn Pogue's historical knowledge, plotting skills, and good judgment are demonstrated in Gwen. Since the novel is aimed primarily at 10 to 12-year-olds, she is careful as to the detail she gives about the unwholesome intentions of the "master of the house" where Gwen is first assigned. The second host family shows Pogue's knowledge of the "Social Gospel" milieu of that era. Advocates of women's suffrage appear a couple of times, putting the story in context and hinting of the broader "women's history" theme. Finally, in taking Gwen to the Brantford area, where Pauline Johnson spent her formative years, Pogue provides a satisfying circular structure, bringing together several threads, and providing some closure in an open ending.

Gwen transforms the image of a "Home girl" from an object of pity to a plucky human being full of talent and ability. I was sorry when the novel ended, and hope for a sequel.

Highly Recommended.

Ruth Latta's four mystery novels and two general interest novels (including the latest, Spelling Bee, 2009) have girls and women as central characters.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- March 19, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |